Soon to be a saint: Staunch Catholic Benedict Daswa was killed by a mob of community members on a rural road in the Thohoyandou area.

Midway through his State of the Nation address on February 2 1990 president FW de Klerk paused, shuffled the papers on the podium in front of him and then uttered a sentence that would transform the course of South African history.

“The prohibition of the African National Congress, the Pan Africanist Congress, the South African Communist Party and a number of subsidiary organisations is being rescinded,” he told the chamber flatly, as though reeling off a list of budget expenditures. “People serving prison sentences because they were members of one of these organisations,” he continued, “will be identified and released.”

The evening of the same day, on a red gash of dirt road 30km outside Thohoyandou, the capital of the Venda homeland, a schoolteacher named Benedict Daswa was driving his white Ford Cortina bakkie home to the village of Mbahe when his headlights flashed across a massive tree branch blocking the road ahead.

He cut the ignition and opened the door to move the felled wood. But as he stepped out of the bakkie, a mass of figures emerged suddenly from the dark tangle of bushes on either side of the road. One of the men lobbed a stone at Daswa, then another. A rock struck the Cortina’s windshield with a crack. He turned and began to run.

Eighteen hundred kilometres from the parliamentary chamber where South Africa’s future had just taken a radical pivot, Daswa sprinted across Mbahe’s parched soccer field, where he had once been coach of the local youth team, and up a nearby hill into a crowded shebeen. But the mob was close behind. They pulled him from a nearby rondavel and formed a tight knot around him. As the crowd moved closer, Daswa – a devout Catholic – began to pray aloud.

“God,” onlookers remember him pleading, “into your hands receive my spirit.”

The blow from the knobkerrie was swift and blunt. Daswa crumpled to the ground, suddenly silent. Members of the crowd surged forward with vats of boiling water, tipping them over the dying man’s folded body.

The South Africa where Benedict Daswa died that February evening in 1990 was hardly a saintly place.

In this South Africa, lines of morality often blurred dangerously as government death squads assassinated teenage activists and township vigilantes necklaced suspected turncoats, as police tested torture techniques on the never-ending stream of arrested protesters and guerrilla soldiers laid down bombs in crowded shopping centres and on busy street corners.

But that world also produced at least one saint – a literal one. In January 2015, nearly 25 years to the day after Daswa’s death at the hands of the mob in Mbahe, the Vatican announced that he would be beatified – one of the final steps to becoming a Catholic saint, South Africa’s first.

That would put the Venda schoolteacher in the storied company of some of Catholicism’s most revered figures, men and women who lived – and died – by their faith so completely that they are considered holy. Most Catholics believe saints have the power to intercede directly with God on their behalf.

“I’m always saying to people here: ‘Don’t forget that from among you, [God] chose a model for all Christianity,'” says Benoit Gueye, the Senegalese missionary who is the parish priest at Thohoyandou’s small Catholic parish (membership: 2 000). “From this far place, from a place completely lost in the bush, that’s where God went and picked his model.”

Indeed, Daswa would be, in many ways, an unusual saint.

For one thing, he was African. Despite the fact that the church is growing faster in Africa than anywhere else on Earth, Africans remain a relative rarity on the roster of saints, particularly among those who lived in modern times. The most recently canonised black African Catholic saints were a cadre of Ugandan martyrs executed by their king between 1885 and 1887, and a Sudanese slave who later became a devout nun in Italy in the early 20th century.

Born Jewish

For another thing, Daswa was Jewish. Born in 1946, he came from a family of Lemba, a Southern African ethnic group that traces its lineage to ancient Semitic communities in the Middle East. He was circumcised as a young child and grew up keeping a diet close to kosher.

But when he was 15, Daswa quietly began to meet with a local Catholic study group that, for want of a church, gathered in the shade of a fig tree. Two years later, he was formally baptised.

From there, Daswa quickly became a revered man in Mbahe. First a teacher in the local primary school, he later became its principal. He married a soft-spoken fellow teacher, Shadi Monyai, and the couple began planting a large vegetable garden on a plot on the outskirts of town, from which they gifted fellow villagers a constant supply of cabbage, tomatoes, chard, onions and mangoes.

Scraping together their savings and income from the garden, the Daswas bought a brand-new Ford Cortina, which they later used to ferry building supplies for the area’s first Catholic church.

One weekend, his friend Chris Mphaphuli remembers, Daswa travelled to the town of Louis Trichardt 75km away, and when he returned he was clutching a starched black pinstripe suit – “something expensive”, Mphaphuli says.

“For a man around here to have a suit like that, it was a very rare thing,” he says. “But it was part of the image he was projecting – that he took his own life seriously, that he was a gentleman.”

But that image did not always sit well in Mbahe, friends say. Daswa was opinionated and didn’t flinch at arguing over sensitive issues, including faith. “He was gentle but he was forward,” says another friend, Simon Khaukanani. “He never backed down from a debate.”

That penchant for an argument – combined with Daswa’s close relationship with the local headman – began to arouse local jealousy.

In another time, in another place, such jealousy might have festered quietly or fizzled away. But Daswa had the bad fortune to rise to prominence at a historical moment when faith, power and politics had become dangerously ensnarled in Venda.

Muti murders

In the late 1980s, the area – one of four allegedly “independent” apartheid homelands – fell victim to a spate of so-called “muti murders”: brutal killings designed to extract body parts for ritual use.

Bodies were found hacked apart in Venda’s lush valleys and remote mountains, and rumours began to ripple out implicating high-level politicians in the homeland’s puppet government. These men, the whispers went, had ordered the hits to create potions that would enhance their own prestige and power. And local people became determined to find – and kill – the so-called witches who were providing them with that muti.

“There have always been people here who are Christians during the day, but by night they still visit the sangomas, still believe in the old ways,” says Alunamutwe Enos Rannditsheni, a Lutheran minister and PhD candidate at the University of Venda who studies ritual murder in the region.

“For many people the church can’t provide every answer, so they maintain that connection.”

But what made the late 1980s and early 1990s particularly volatile was that ferreting out witches was not simply an act of spiritual healing, but one of political redemption as well. Kill the witch, the logic seemed to go, and you were helping to kill the homeland system too. And indeed, Venda’s courts were soon swamped with cases of so-called “witch-burning” – 217 of them between January and April 1990 alone.

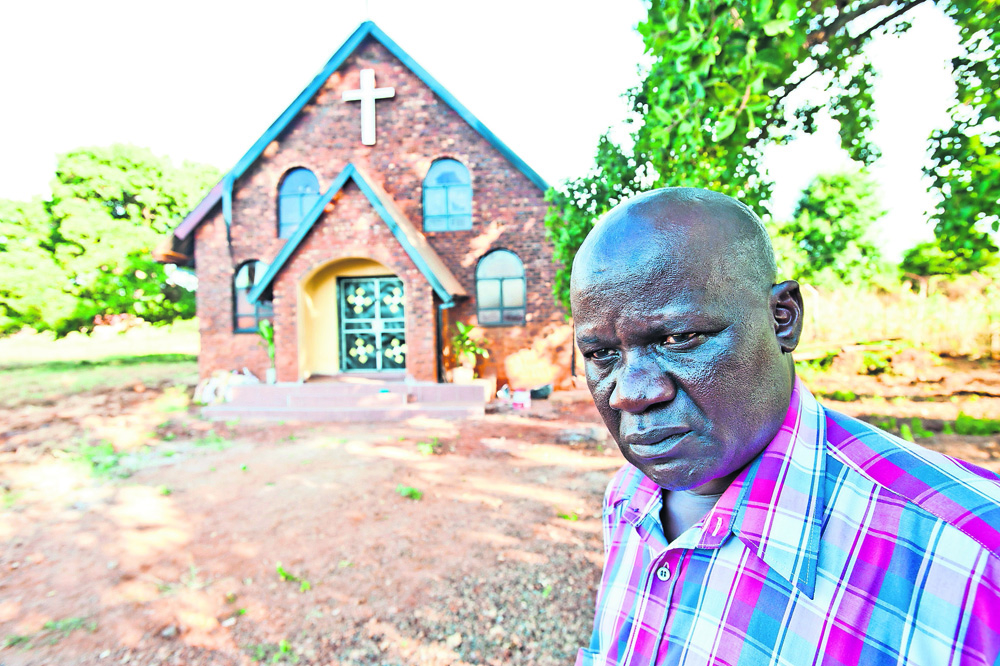

Lasting memory: Chris Mphaphuli in front of the Catholic church that his friend Benedict Daswa helped to build before he was killed

As one participant who later applied for amnesty at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission explained: “Our ‘comrades’ in the urban areas were involved in rent boycotts, consumer boycotts, strikes and the like, whereas here in the rural areas there were no such things, so there came to be a time when we thought that for us to contribute in our struggle, we have to remove such obstacles that were making it difficult for us to be free … those witches had to be eliminated before we got that freedom because it is no use getting freed with obstacles on our doorsteps.”

In November 1989, several days of unusually heavy thunderstorms rattled the Thohoyandou area, turning the red road to Mbahe into a thick paste and drawing renewed concern that the witches were at work nearby.

Two months later, at the end of January 1990, a particularly vicious lightning storm scorched multiple huts in Mbahe and community members, their nerves frayed, decided it was time to take action.

They called a village meeting and determined that each family would contribute R5 to hire a sangoma to divine who was responsible for the lightning strikes. Daswa refused to chip in a coin. It went against his Catholic faith, he told them bluntly.

A few nights after the meeting, Daswa agreed to transport a local man with a heavy bag of mealies to his home in an adjacent village. He was driving back along the jolting dirt road to Mbahe when he came across the branches blocking his path and stopped his bakkie to investigate.

In other corners of Venda, those killed in the early 1990s were suspected witches. In Mbahe, however, it was the man who refused to sanction the killing.

“The witchcraft-related murders that went on then were a barometer of the vast social confusion of those times,” says Anthony Egan, a theologian with the Jesuit Institute South Africa. “And Benedict Daswa had the audacity to stand up and say: ‘Chaps, we can’t kill for this.'”

No one was ever convicted for Daswa’s murder – in part, friends say, because witnesses were afraid of retribution if they spoke up. But locals say that at least some of the killers still live among them.

But in the years that followed Daswa’s brutal death, friends and neighbours from nearby villages began to gather at the local church each November to commemorate his life.

A decade later, the local bishop, Hugh Slattery, took notice of the celebrations and began to dig into Daswa’s biography. Here, he thought, was an example of a devout man murdered for his faith – it seemed the perfect storm for Catholic sainthood.

“I was interested because so many people around here clearly regarded him as a role model, and I think we’re all looking for heroes,” Slattery says.

Docket of evidence

The investigation plodded along for years, as local faith leaders slowly gathered evidence of Daswa’s prospective saintliness. In 2009, they submitted a 1 000-page docket of evidence to the Vatican.

Then, in January of this year, the Catholic Church announced that the Venda schoolteacher would be declared “blessed” – the immediate precursor to becoming a saint. For full canonisation, church leaders must still prove that there is at least one miracle directly attributable to someone praying to Daswa. The beatification ceremony will take place on September 13.

On February 10 1990, a week after Daswa’s death, hundreds of mourners packed into the simple Catholic church that he had helped to build in Nweli, near Mbahe, to say goodbye to their friend and neighbour.

The crowd was so large that it spilled out of the squat brick building and into the yard around it. The women dressed in traditional, boldly striped Venda nwendas; some of the Lemba men wore yarmulkes – the Jewish skullcap. When the funeral mass finished, they poured out into the road behind the hearse, wailing burial songs as they retraced the same path Daswa had taken the week before, past the spot where he had abandoned his car and on to Mbahe’s simple graveyard. There, they laid down his coffin and covered it with chalky red earth.

“For me, Benedict Daswa is a reminder that saints are not extraordinary, that they were once people who walked among us, who were members of our communities,” says Gueye, Thohoyandou’s missionary priest. “This was a simple man who was a witness of Jesus in the world, and who was willing to die for that.”

The day after Daswa’s funeral, on a sun-spattered Western Cape summer afternoon, Nelson Mandela gripped his wife Winnie’s hand and they both raised a curled fist as they walked through the open gates of Victor Verster prison and out into a new South Africa.

Ryan Lenora Brown, a freelance writer who lives in Johannesburg, is the author of A Native of Nowhere: The Life of Nat Nakasa