Tools of the trade: Evidence of Sam Maseko's addiction. His mother Audrey at least knows where Sam is now; he used to wander around and steal.

Jessie Cohen

BECAUSE THE NIGHT by Stacy Hardy (Pocko)

For Stacy Hardy – author of a newly published series of short stories titled Because the Night – “bodies are unruly things, vicarious entities: they get ill, they experience strange desires, they’re always knocking something over and tripping up.

“The page,” Hardy tells me, “is where I seek to express the body in all of its vulnerability.”

To tread the line between private and public expression, Hardy adopts the point of view of young, uncertain female protagonists who negotiate urban and rural South Africa and, indeed, their own bodies through unabashed submission to a desired male other.

In what is described by the publisher as “uniquely female insights into sex, love, intimacy and power”, Hardy paints an image of women stuck in a state of perpetual waiting. For many of the characters, deliverance is envisioned through the willed actions from a lover, brother or ex-partner either to call, fuck or find her. Female passivity is the name of the game.

According to Hardy, the short story is the perfect literary form to express women’s experience. “As opposed to the masculine grand narrative, it allows for uncertainty.” Yet, with ironic conviction, she tells me: “This is not feminist literature. I’m just a chick writing about South Africa from a woman’s perspective.”

Unsung female experience

To push against “didactic” feminist rendering of female experience, Hardy’s stories hang together through a jaunty but developing stream of consciousness: While a teenager caves into peer pressure to “fuck [her] feminist crap” and take part in a wet T-shirt competition, another character reads as self-assured, telling a room of men that her breasts are “womanhood! Femininity! Self! Sense of self!” But, it transpires, even this bold character struggles to grasp her womanhood without male validation.

We begin with two women peeing in the bush – “pee sisters” lower their “aching fannies” to share in what Hardy sees as “a quintessential South African experience”. “Its a great opening for creating discomfort and uncertainty”, Hardy tells me, adding: “Peeing in public puts women in a vulnerable position. Guys can just whip it out, but as women we’re negotiating a constrained social ‘code’”. This attempt to document “unsung” shared female experiences is somewhat laboured but no less thrilling for the way it recasts the “noteworthy” in literature and South African arts in general.

Fearlessly crude language

Many stories venture into the erotic where bodily exploration holds no bounds. In “Squirreling”, we enter a masturbating scene which rapidly turns into a visceral fantasy. The protagonist is mourning a break-up and starts tentatively plying her vagina with household objects that remind her of him, but, when she moves to squatting on her toothbrush things take a turn for the surreal. She imagines that the bristles are “a squirrel orchestra” which she stuffs inside “by the fistful” until she is “swollen and moist”. The language is fearlessly crude, reading, at times, like a punch to the stomach – a remedy, perhaps, to the often alienating portrayal of women’s feelings in the “grand” canon, which have been predominantly framed by the male imagination.

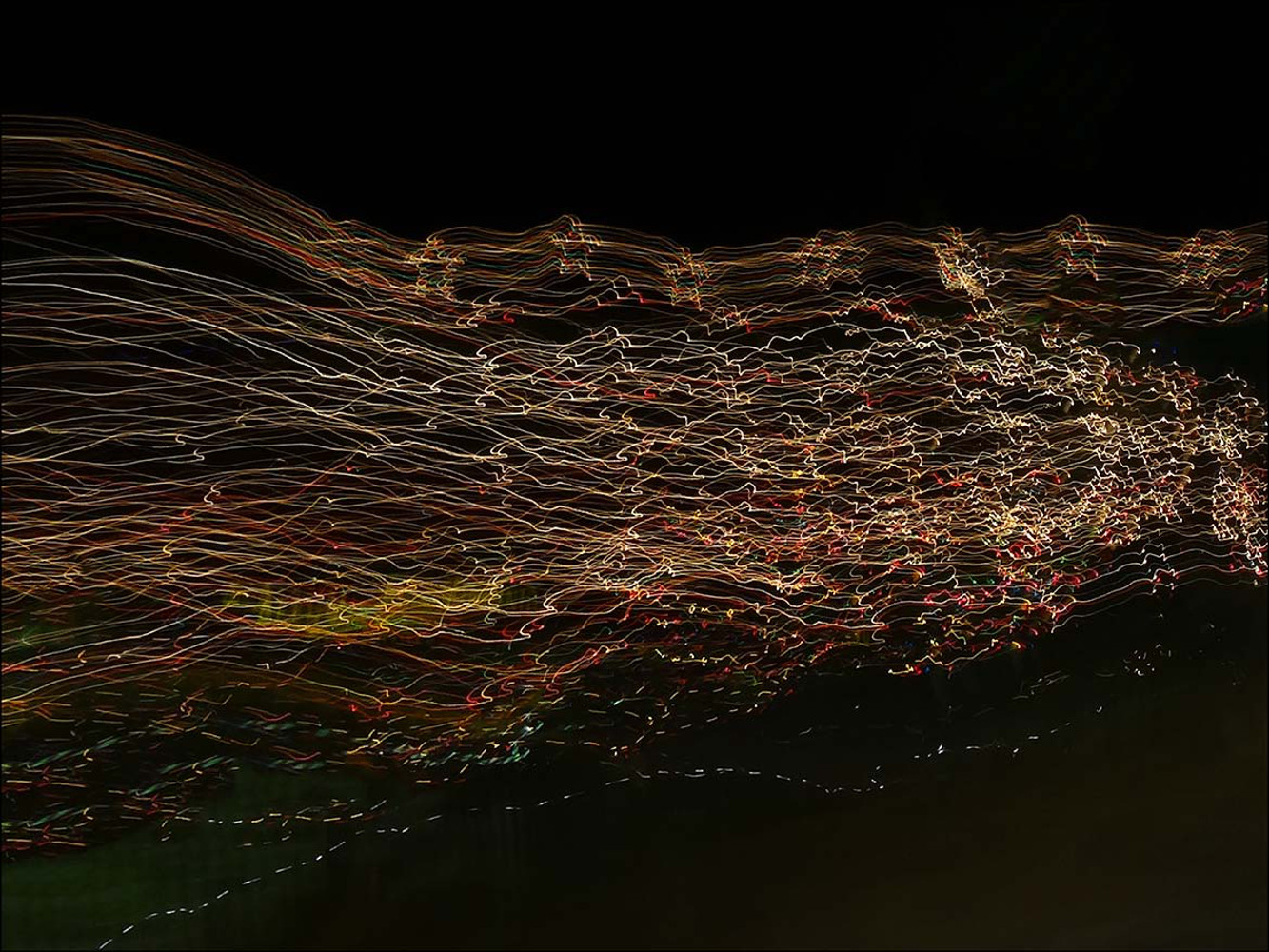

The intensity of the writing is broken up by abstract nightscape photographs taken by Mario Pischedda, which accompany each story. With haunting allure, each shot depicts a different formation of light shooting through darkness, enhancing the sense of a fragmented psychological journey developing across the page. Even Hardy admits that, until she saw the images and text compiled together by Pocko, she had “not realised how much of a road movie the book is – so much about transitions and moving through space”.

Critical shift in consciousness

In “Story Sums”, the travelling metaphor in the context of women’s growth is strikingly portrayed. A young couple are stranded at the side of a road, fearing for their lives as dusk falls in desolate, rural Transkei. In a fit of frustration the man walks away and disappears into the darkness, leaving the woman with “a sudden sick feeling. The realisation. He’s gone”.

At first, she “mimics his pace” and tries to “match his stride”, but, as she walks alone she feels stronger, striving to “outpace him … metres ahead, flying!” The photograph [below] that follows the story resembles light bursting through clouds, evoking a critical shift in consciousness where women finally breaks through internalised barriers and feels her way through the dark.

Because the Night must be celebrated for stretching the boundaries of “acceptable” female experience in literature. It offers an empowering, escapist journey for women, especially relevant to a South African readership, where perceived danger lurking in dark public spaces severely curtails women’s mobility and expression.

What’s more, by pushing the boundaries of form and taking the scope of female experience to the edge, the book also challenges a narrow feminist perspective to allow for womanhood to emerge in all its fraught complexity as an organic trajectory where self-objectification and un-PC desires are explored and judgment holds no place.