All the World's Futures: 139 artists are exhibiting at the 56th Venice Biennale this year.

“Everyone is working happily, the sun is shining all the time. It’s totally awful,” says the voice. We are in Venice again, reclining on white sun-loungers in a dark space, illuminated by a grid of blue light. Up on the screen people are dancing, joking and pretending to be killed. Hito Steyerl has plunged us into a video game motion-capture studio, in the German pavilion at the 56th biennale. It is a world of total surveillance and artificial pleasures. “I’m not sure where the game ends and real life begins. It turns out you are your own enemy and you have to make your way through a motion-capture studio gulag,” the voice explains, laconically. She could be talking about the biennale, whose keynote theme, this time, is All the World’s Futures.

While national pavilions each do their own thing, the main exhibition in the central pavilion, and running through the medieval dockyard buildings of the Arsenale, is curated by Okwui Enwezor. You cannot curate an entire world, or all its possible futures. That would be God’s job, but Enwezor has hubris enough to try. If his exhibition fails, it does so on a grand scale. There is too much to take in, too many artists – 139 of them – to get to grips with. Compendious and difficult, All the World’s Futures has everything from contemporary images of caged and ditch-digging convicts in Louisiana to the depression-era photographs of Walker Evans. Here are the gorgeous new paintings of Chris Ofili , lush and swooning against walls of hand-painted foliage. Here are the horrible new paintings of Georg Baselitz. (I can’t understand for the life of me why he is here.) We can dip into the entire film corpus of the late Harun Farocki and play among the 108 objects in Qiu Zhijie’s magical theatre of hanging lanterns, lighthouses and suspended birds. Sometimes, a great bell tolls.

Nigerian Emeka Ogboh has recorded the voices of African refugees, denied formal residency, singing a stanza from the German national anthem in their own languages. They sing a song of belonging to a country that doesn’t really want them. It is in such small moments that All the World’s Futures comes alive, touches us and makes us think of where we belong.

Although Enwezor’s exhibition contains the usual roster of big-name canonical artists, including Bruce Nauman, Isa Genzken, and Hans Haacke, he also includes many Middle Eastern, African and Asian figures little known in the west. And at the heart of All the World’s Futures stands Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, which is being read from end to end in the Arena, an auditorium designed by David Adjaye in the central pavilion. Directed by Isaac Julien, two readers plough through Marx’s great work in a series of daily readings.

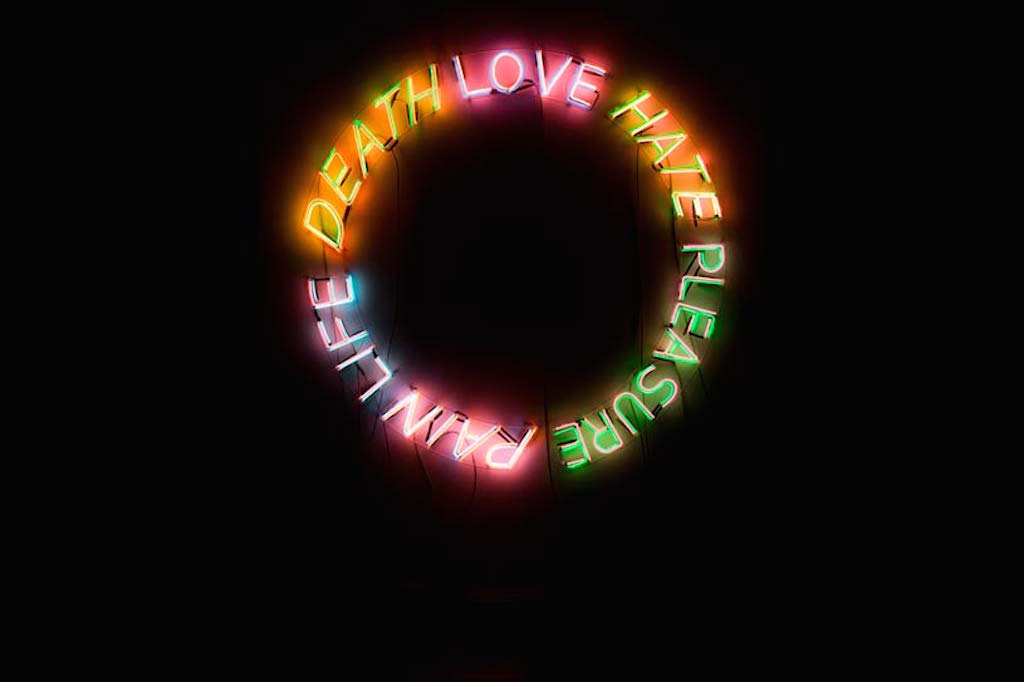

Life, Death, Love, Hate, Pleasure, Pain by Bruce Nauman (Image via labiennale.org)

A monument to possibility and its failure, the reading of Marx is also a good way to get contemporary art’s audience to begin looking and thinking differently, even if not in Marxist terms. It offers an alternative horizon. But you walk as much as think your way through the biennale. A walk is a narrative, a picaresque filled with encounters and diversions. The long path that runs beside the medieval Corderie has been lined on either side with sewn together cocoa sacks. Ibrahim Mahama’s Out of Bounds is filled with incident – the sewn-on metal tags, the knotted ropes, the gaping holes and scribbles on the hessian. It is an evocation of a raddled world as much as a collection of thousands of sacks. It also speaks of labour: from the production of the sacks in south-east Asia, to their later use in the unregulated cocoa industry in Ghana, then their laborious repair in Mahama’s construction of these great curtains. This cumulative work – and the exhaustion that accompanies it – is acknowledged in our own walk between its sagging walls.

Standing among the Styrofoam boulders, drapes and deserts of spray-painted and graffitied cement in Katharina Grosse’s Day-Glo wasteland, I felt as if I was waiting for Enwezor to lead us out of this. Which way to go? To plunge into an operatic installation hung with banners, interspersed with video scenes of the naked artist Lili Reynaud Dewar, posing and dancing around libraries and drawing rooms, and which deals with a controversy about barebacking in the age of Aids? Or to be terrified by Abu Bakarr Mansaray’s drawings of bizarre machines, including a nuclear telephone “found in Hell” and an armoured tank that chews up human bodies? Mansaray’s complex and obsessive drawings were a personal reaction to trauma in the Sierra Leone civil war. “I have seen all this, and I know these machines work,” he told me.

At one of the sleek corporate desks I sign a contract. I could have made a personal declaration that “I will always be too expensive to buy”, but that was clearly a no-no, so I put my signature instead to a form stating that “I, the undersigned, hereby certify that I will always mean what I say.”

Tall order, but I signed it anyway. The declaration will be held, I’m told, in the Adrian Piper Research Archive in Berlin for 100 years. I’ll be long gone. Elsewhere, Piper is showing a number of school blackboards, on which are written the lines “Everything will be taken away” over and over again, like a classroom punishment. On Saturday, Piper won the Golden Lion for best artist at the biennale.

Enwezor’s show is unremitting. It begins with black painted flags by Oscar Murillo, draped funereally at the entrance to the central pavilion, and its first rooms are dedicated to signs of the end. John Akomfrah’s new three-screen film, Vertigo Sea, with its BBC natural history unit shots of oceanic life, descends into old footage of the barbaric whaling industry, and black bodies washed up on the beach. Flenched blubber and human corpses lie under wheeling flocks of seabirds, while pods of whales call and blow in the waves. Akomfrah’s film is a pained lyric to a passing world.

What could be so sexy as the end? In St Mark’s Square, New Zealand artist Simon Denny is riffing on the aesthetics and graphic style of the NSA PowerPoint slides that Edward Snowden leaked. Denny’s project, with its computer server-rack displays, is installed in a Renaissance library where the machinations of state security are themselves surveilled by allegorical scenes painted by Titian and Veronese. The philosophers and gods on the walls and ceiling look worried, as well they might be.

Trees are slowly turning on great moving clods of earth at the French pavilion. Sarah Lucas’s great yellow dong looms under the portico. The Canadian pavilion has been turned into a Quebec corner shop. There are more shops: a newspaper kiosk and an adults-only porno-comic bookstand in the Spanish pavilion, and a wretched taxidermy shop that fills the Greek pavilion. Weird translocations are the order of the day. A long, curved panoramic screen fills the Polish pavilion. Day breaks in a Haitian village. A Polish opera company arrives, sets up and performs Stanislaw Moniuszko’s Halka, written in 1848. Throughout the outdoor production a tethered goat bleats. A transposition of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, CT Jasper and Joanna Malinowska’s film has further, hidden trapdoors. The Haitian village is inhabited, we are told, by descendants of Polish soldiers who disobeyed Napoleon’s orders to put down a slave rebellion in 1802, and aided the rebels.

Joan Jonas fills the US pavilion with the contents of her dreams, her memories, the stories that have clung to her. Little filmed performances, home-movie footage (walks on the beach, playing with dogs), stage props, repeated images of bees and fish and stars line the walls between the screens. Jonas’s art is captivating but impossible to unravel. There’s just too much stuff.

An artificial and slightly unpleasant smell of babies wafts through the Swiss pavilion, as we approach a gurgling pink sea of liquified cosmetic products. Out on a lawn, Carsten Holler’s fairground carousel is being erected. When it is running, it’ll be a slow ride to nowhere. Someone has done something with miles of string in the Japanese pavilion, the Israeli pavilion is covered in tires, and Finland smells like a forest.

Danh Vo, representing Denmark, has painted one room entirely red, the walls covered in the sumptuous cochineal crimson the Spanish imported when they colonised Mexico, and provided the papal state with an alternative to the Chinese red silk that was no longer available to them. The delicacy and profanities of Vo’s installation (lines from the demonically possessed child in The Exorcist are written next to a 13th-century sculpted figure of Christ) are deftly handled.

Across Venice, at the Punta della Dogana (owned by the Pinault Collection) Vo has assembled and curated Slip of the Tongue, an eccentric exhibition of art from the 13th century to the present, juxtaposing Vo’s own work with major contributions from Nancy Spero, David Hammons and Nairy Baghramian. Slip of the Tongue proceeds as a series of dramatic conversations and confrontations. Compared to the biennale, where it’s one damn thing after another, everything is given the space it needs.

All biennales suffer from their own excess, and the Venice Biennale is the mother of them all, the most excessive. I have never seen one that doesn’t run out of steam. Slip of the Tongue, on the other hand, never misses a beat. Wherever we find ourselves we seek the exceptional, the singular voice. Vo lets the objects speak and I left speechless. All the World’s Futures tells a different story, of a world too complex to submit to any single critique or system, even Marx’s. I have seen the future and I’m not going. – (c) Guardian News & Media Ltd, 2015