Michael Caine and Harvey Keitel in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth.

The posters, the trailers, the teaser trailers, and the teaser posters are all emerging. And though it is rash to generalise, there is a certain preponderance of flesh, lust and concupiscence at this year’s Cannes film festival. In Valérie Donzelli’s Marguerite et Julien, there is incest. In Todd Haynes’s Carol, starring Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara, there is forbidden love. In the poster for Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth, a somewhat haggard Michael Caine and Harvey Keitel appear to be ogling an unclothed young woman from the vantage point of their hot tub.

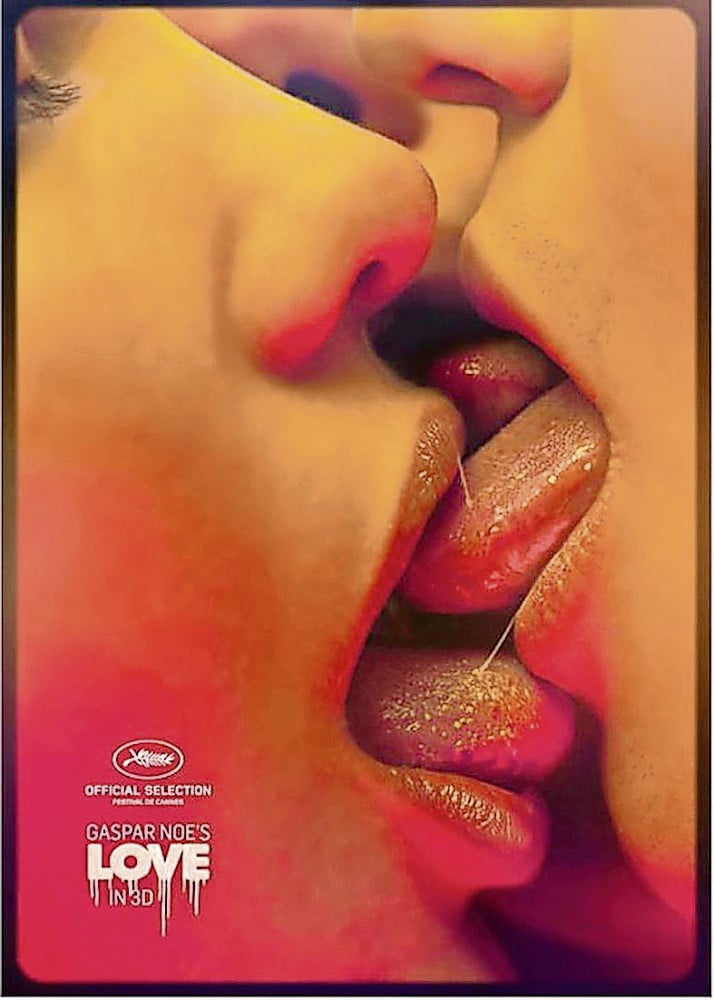

And perhaps most startlingly of all, the great enfant terrible Gaspar Noé has revealed on the web an explicit “poster” for his quaintly titled Love, the 3D sex film that is showing as a midnight screening. It is not clear whether this poster could possibly exist anywhere but online. Displayed in shopping malls and tube stations, it might mean that members of the public wishing to walk past it must present proof of age to a specially positioned squadron of police to show that they are 18 or over.

Even when there is no actual sex on the screen, there is always a great deal of intensely publicised sexiness at the festival. The gowns, the bling, the paparazzi, the swimming pool at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc – it is all suffused and perfumed with generalised sexiness, a concept that merges with being rich, famous and desirable. Cannes encourages a televised theatre of glamour on the red carpet every night, which is adored by L’Oréal, the festival’s major sponsor. In their hearts, some people believe that this kind of sexiness is sexier than sex.

Long before reality television and the Kardashians, the concept of Z-list celebs publicly cavorting in a state of undress was pioneered at Cannes with the semi-official tradition of “starlets” appearing in skimpy swimming costumes on Promenade de la Croisette. In 1953, 18-year-old Brigitte Bardot posed in a bikini opposite Kirk Douglas.

The next year, the now-forgotten actor Simone Silva went topless at Cannes opposite a bemused Robert Mitchum. In 1964, Jayne Mansfield also appeared in her swimming costume and did an unedifying dance called the Monkey Bird with her chihuahua. Each event triggered huge overexcitement among the jostling photographers, in an age when this kind of photo op was not as strictly policed as it is today.

But there was also a good deal of scandale up on the screen. In 1961, Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana won the Palme d’Or. The strong sexual content of the film, about a woman on the verge of becoming a nun visiting her reclusive uncle, astonished and outraged many at Cannes – and indeed the Catholic Church. In 1962, the bow-tied audiences at the festival were similarly affronted by Mondo Cane. Directed by Paolo Cavara, Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi, Mondo Cane was an explicit “freakumentary” using genuine (and sometimes less-than-genuine) archive footage showing weird sexual rituals from all over the world, including a rite of passage in Nepal in which Gurkhas dress in women’s clothing.

Shockable though Cannes audiences have always been, the idea of being upset simply at sex became a bit passé, and the shocking films became increasingly about violence, from Michael Haneke’s Funny Games to Noé’s Irréversible. But sex is always a hot ticket at the festival. Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotape, the Palme d’Or winner in 1989, will hardly seem shocking to modern audiences, but the idea of videoing oneself talking about sex was racy for its time.

In the 1990s, we saw Larry Clark’s Kids, a disturbing film about the sex lives of teenage New Yorkers that was widely condemned as exploitative and quasi-paedophilic. A critic friend said that the first press screening for Kids was so packed and disorderly that he had the shirt ripped from his back in the mêlée outside. A year later, David Cronenberg unveiled his Crash, a version of the JG Ballard novel about a sexualised fetish for car crashes. The film was probably the last great censorship and moral-panic case in Britain surrounding a sexually explicit film.

In the new century, Cannes revealed itself to be diverted and overexcited by several explicit films that appeared in the market, though not in the official selection. One was Baise-Moi (Kiss Me or, ambiguously, Fuck Me), about two young women who go on a kind of Bonnie and Bonnie tour of sex and violence, from the writer-directors Coralie Trinh Thi and Virginie Despentes.

In 2004, Michael Winterbottom’s interesting and underrated 9 Songs was also in the market rather than the official selection, and generated a huge amount of interest for its (rather romantic) view of obsessive, consenting sex. Two years earlier Carlos Reygadas’s Japón, which showed in the Director’s Fortnight, became a great talking point for showing a middle-aged man having sex with a very old woman.

Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny was squawked and screeched at in 2003 for what was admittedly a self-important and self-indulgent display, culminating in Gallo copping a 10-minute blow job from Chloë Sevigny. The scene was supposedly authentic, though undermined by on-set reports of a large and realistic-looking phallic prosthesis being used.

In more recent years, John Cameron Mitchell’s Shortbus, which played out of competition in 2006, provided a wacky panorama of “pervitude”, beginning with a shot of a man bending over and giving himself oral pleasure. It becomes a mosh pit of mass fornication in which someone murmurs: “Isn’t it great? Like the sixties, but without the hope.”

French films about sex tended to be very gamey and very serious in a way that only French cinema can manage. Jeune et Jolie, in competition in 2013, was a film directed by François Ozon that swooned over the sexiness of a beautiful teenage girl who becomes involved in high-class prostitution: it was a romanticised view of bought sex. Ulrich Seidl’s far more brutally candid Paradise: Love tackled sex tourism in Kenya and was decidedly unsexy.

It is a perennial complaint that gay sexuality and gay relationships are underrepresented at Cannes, and that the festival is a quite conservative and heterosexual institution. Perhaps it is, though Wong Kar-wai’s much admired Happy Together, which showed in 1997 and examined the love affair between two men played by Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, is often cited as a great gay movie at Cannes.

Carol

The Queer Palm was founded by journalist Franck Finance-Madureira in 2010 to recognise lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender-relevant films at the festival. The award has gone successively to Gregg Araki’s Kaboom, Oliver Hermanus’s Beauty, Xavier Dolan’s Laurence Anyways, Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake and Matthew Warchus’s Pride. Of these, I think the best is Stranger by the Lake. A thrilling and fascinating story about a murder in a gay cruising spot, it’s intensely and passionately about sex in a way that straight films typically aren’t.

Abdellatif Kechiche’s Palme d’Or-winning Blue Is the Warmest Colour, showing the love affair between two women, has a real claim to be the most sexually explicit film to have won the big prize at Cannes, although many commentators, gay and straight, dispute the idea that this is an example of gay or queer cinema – more an example of the straight world’s perennial fascination with lesbians. But sexy it certainly is.

And I think Nicole Kidman’s masturbation scene in Lee Daniels’s much-misunderstood Florida noir The Paperboy – in competition in 2012 – is funny and sexy.

But for my money, the best sex film ever presented at Cannes was Polissons et Galipettes (or Rascals and Romps), directed by Cécile Babiole and Michel Reilhac. Shown in 2002, it anthologises a dozen sex films furtively made in France between 1905 and 1925 to be shown in brothels and at stag parties. A chapter in the secret history of sex and the belle époque, it’s bizarre and hilarious – and in Britain was awarded the notorious R18 certificate (stricter than 18 and requiring licensed club conditions), evidently on the grounds that it shows a woman dressed as a nun pleasuring herself with a Jack Russell terrier. That was probably the supreme Cannes sex moment. – © Guardian News & Media 2015

The Cannes film festival runs until May 24