Carol Campbell gives us a classic balance of good and evil in her novel

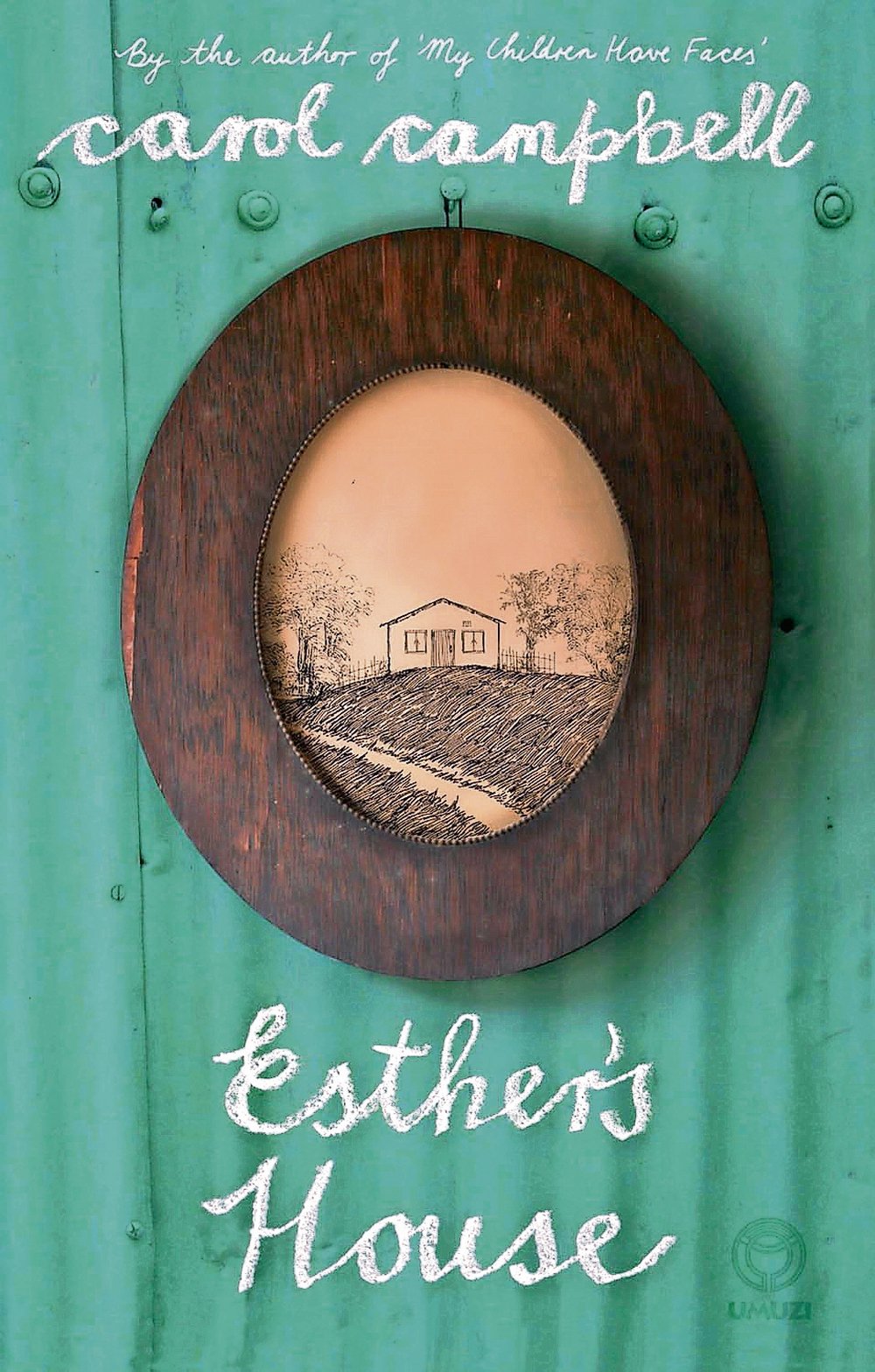

ESTHER’S HOUSE by Carol Campbell (Umuzi)

The main characters in this novel have never set foot in a shopping mall. In the tradition of that great moving novel of the 1990s, A Place Called Vatmaar by AHM Scholtz, Esther’s House looks at the lives of the poor and marginalised, people who have almost nothing materially but aspire to dignity and recognition of their humanity.

For Esther a house with an inside tap and a flush loo would make her feel human.

This pearl of a novel reads swiftly and simply; the author arrests the reader at once with the clarity and detail of her observations and the economy with which she gets us into the heart of her novel, in a fine combination of elegant English and lokasie Afrikaans (bekslaner – a gate, mafelletjie, metjies). Campbell’s acclaimed first novel, My Children Have Faces, is also about the marginalised, the karretjiemense.

She tells the story of Esther Gelderblom and her neighbours in a lokasie outside Oudtshoorn where they have been waiting 20 years and more for RDP houses, living in shacks in the backyard of a man who rules them mercilessly with a sjambok and threats of eviction. Esther and her neighbour and friend, Katjie Witbooi, have been on the housing list for two decades. They go every month to check what progress has been made. They know everyone in the queue and, in recent years, they see young people and foreigners also queuing.

Campbell tells how the newest houses, not even finished, are occupied by the desperate. She describes what it is like to be on the inside of a service delivery protest, behind the burning barricades of tyres and hiding from the teargas. Esther and Katjie are in the middle of all this, frightened, hungry and fed up.

When one neighbour, Titty, a young girl with a toddler, who has been living in a pipe, suddenly gets a properly allocated house, Esther realises something is not right. Although Titty is amoral and opportunistic it is hard, in the end, to condemn her when you know her whole story.

Esther shows us what it means to be neighbourly, to be one of the uitkyk anties who observe everything that is going on, and not only comment but also help. We also meet the kerksusters of Esther’s church, Esther’s children and husband, and their lives in this community. Esther herself has been a drinker (a good friend with the papsak), but she has joined the church. And when a neighbour’s child dies she feels deeply remorseful that she did not take him in.

Despite their bitter poverty it is usual to share what little they have, but when the housing list corruption starts, even Esther begins to take a hard line for a while. The corrupt officials in this novel get what they deserve in incidents that are entirely believable and very satisfying to the reader.

There is respite for the reader in unexpected places, for example when Esther lands in hospital she wakes to find she has company in the ward: “His small clipped moustache and the battered briefcase lying open at her feet told Esther he was a policeman. From where she lay she could see the cuffs of his white shirt were worn but the button at his throat was fastened and his grey tie was neat.”

There is much more of this, describing a cop who knows how to listen and what to do. Campbell gives us a classic balance of good and evil; in Esther’s House she refutes the dead hand of cynicism in a novel that reflects real issues in our current situation, 21 years into democracy.