In less than the time it has taken to get just one of the six units at Medupi power station going, South Africa, through private renewable power producers, has bid for, developed and built the equivalent of almost the entire nameplate capacity of the as yet unfinished coal-fired plant.

In the four years since its launch, the government has procured 4 322MW through the renewable energy independent power producer programme, according to the energy department. More is on the way.

Power utility Eskom says 40 projects have been connected to the grid, with another 50 under way.

Ground was broken on the 4 800MW Medupi station in August 2007. Eight years later it is due to begin operating fully only in 2020.

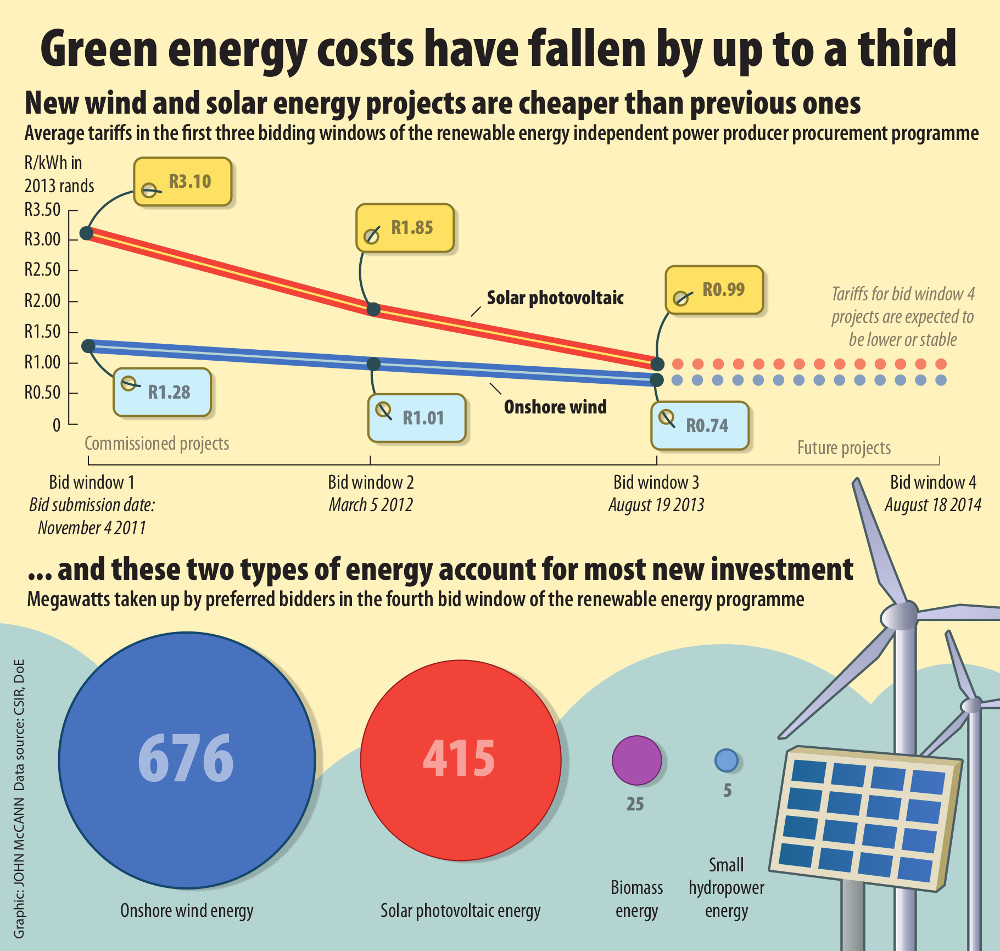

In the fourth bidding round of the renewables programme alone, bids totalled more than 5 000MW for an allocation of 1 105MW.

The good news for the capital-constrained state and burdened taxpayer is that almost the entire programme, estimated to be between R168-billion and R193-billion, has been funded by the private sector.

Investment easy to double

Players in the renewables industry say this investment could easily double. They say that, as the programme further proves itself, it will continue to attract capital from a host of sources.

This success of the renewables programme stands in stark contrast to the difficulties Eskom has had constructing Medupi and its sister station, Kusile.

The most recent cost estimates, reported by the Mail & Guardian in February, put Medupi’s price tag at R154.2-billion, having ballooned from the 2007 estimates of R70-billion. The price tag for Kusile was about R172-billion versus the original estimates of just over R80-billion.

The delays and cost overruns on these projects have put enormous pressure on Eskom’s finances, and on the electricity-starved grid. Without the additional capacity Medupi and Kusile were meant to introduce, Eskom has been burning through diesel to run its expensive peaking power plants. When this has not been enough, power to the country has been cut.

This week the National Energy Regulator, Nersa, held public hearings on Eskom’s application for a 25% tariff increase, in part, to fuel these generators.

Funding gap

At the same time the government is scrambling to fill Eskom’s R225-billion funding gap, having already converted a R60-billion subordinated loan into equity, while it plans a further R23-billion cash injection into the parastatal.

Plans are also afoot to sell off noncore government assets in a bid to find more money for the parastatal.

The renewables programme has saved the country money. Energy from the first wind and photovoltaic (solar PV) projects has saved the power system R3.64-billion in diesel and coal fuel costs, according to research by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research’s Energy Centre, released in February.

Using data from 2014 it also showed that wind and solar power avoided an estimated 120 hours of unserved energy, saving an additional R1.67-billion. Unserved energy is the opportunity cost to electricity consumers and the economy because of electricity supply interruptions.

The research also revealed the extent to which the price of renewable power has declined over the various bidding windows.

It dropped from an average of R3.10 for solar PV and R1.28 for wind in round one in 2011 to an average of 99c a kilowatt hour and 74c/kWh respectively in window three in 2013.

Cheaper than Eskom

These numbers are now almost on par with, or cheaper than, the average standard Eskom tariff, which, according to Nersa, will be 79c/kWh for the 2015-2016 financial year – without taking into account the additional money Eskom is likely to be granted under its reopened tariff application.

The cost of power from Medupi, once items such as interest during construction are accounted for, has previously been estimated at about 97c/kWh.

The renewables programme has proven how well the government could work as a facilitator to the private sector, says Chris Yelland, managing director of EE Publishers.

“We’ve seen these projects coming on stream, on time and on budget,” he says, without relying on the fiscus or guarantees from the government.

Almost 28% of the funding of independent power producer (IPP) projects has come from foreign sources, mainly private equity, according to the IPP office.

Domestic funding of the IPP projects has come primarily from banks, private equity, development finance institutions and institutional investors.

Request for proposals

In April, the energy department announced that, with the selection of preferred bidders for its fourth window, it would release a request for proposals for an “expedited” procurement round of a further 1 800MW. This round would be across all technologies and open to unsuccessful applicants from the previous bid windows.

Minister of Energy Tina Joemat-Pettersson also announced her intention to make a determination for an additional 6 300MW under the renewable programme.

Developments on the procurement of baseload power from independent producers of coal and gas are also under way – with the government aiming to procure more than 3 000MW through its gas-to-power procurement programme and 2 500MW from coal.

“There are more and more sources of capital coming into this market,” says Mark Pickering, managing director of Globeleq South Africa.

Renewable energy has become a global industry and South Africa has followed the trend for the majority of investments in new power generation to be in renewable energy, according to Pickering.

Compete for capital

The coal and gas programmes may compete for capital with renewables projects, but discussions are under way to “dollarise” the power purchase agreements for gas-fired power, says Pickering, because much of the gas imported would be in dollar terms rather than rands.

This will expose these projects to “a much larger pool of debt and equity providers”, he says, adding, “If that’s the case, there may not be that much competition in the local capital markets between the very big, very expensive gas projects and the renewables programme.”

Innovative ways are being found to finance development of renewable energy, such as the establishment of yield companies (yieldcos), says Pickering (see below).

The IPP office – a joint unit set up by the department of energy, the national treasury and the Development Bank of Southern Africa and established to manage procurement for the various independent power producer programmes – said this week there was “sufficient depth in both the financial and capital markets to cover the renewables and other IPP programmes … with a possible increase above 30%.”

There have been arguments that as the renewables programme expands funding by local private equity firms and banks would steadily dry up.

International utilities

But Davin Chown, chairperson of the South African Photovoltaic Industry Association, says that later bid windows – which power prices for developers have reduced dramatically – have been marked by the entrance of major international utilities, with large balance sheets at their disposal.

This includes the likes of Italian utility Enel. Its green power division was selected as a preferred bidder to supply 425MW of wind power in the fourth bid window.

The emergence of these “large balance sheet players” will become prominent, argues Chown.

Local financial institutions remain upbeat about potential for renewables and other IPP programmes.

These developments could be debated, but it is “clear from the outcome of round four that the majority of the projects were still funded via project finance structures, mainly through the local banks”, says Ntlai Mosiah, head of power and infrastructure at Standard Bank. “Only a handful of projects were funded through corporate facilities.”

Given the current and ongoing support from the government for the renewables programme, it is likely to remain an industry to support while the secondary market is developing, he says.

Standard Bank was is “actively involved” in the other IPP programmes.

Allocation and grid connection a problem

The further opening up of South Africa’s energy market to renewable and other independent power producers is hindered by two features: the allocations of new projects by the government and the ability to connect these projects to the grid.

The state’s willingness to increase procurement from renewables, through its expedited bidding round, for an additional 1 800 megawatts (MW), as well as coal and gas was positive, said Mark Pickering, the managing director of Globeleq South Africa.

But Eskom’s ability to provide grid access to projects in later rounds was a concern and likely to get worse, he said.

A creative solution had yet to be found but would require some kind of partnership between the government and industry.

Eskom said the integration of these projects with the grid were challenging because of uncertainty over the location of renewable generation and the timing of the connections.

The concentration of the projects in resource-rich areas, or areas with a great deal of wind or sun, typically necessitated significant strengthening of the networks and upgrades at major substations to ensure that the generated power could be distributed effectively.

It conceded that this was leading to increasingly long lead times to connect projects.

In light of its capital constraints, Eskom said it was developing a “strategic plan based on generation forecasts and renewable energy resource locations, in an effort to provide a blueprint for investing in strategic assets and unlocking corridors to enable future integration of renewable energy generation”.

It had also made some do-it-yourself options available to independent power producers to enable them to build the necessary infrastructure to facilitate their grid connections.

Industry sources said the costs of this were being passed on to developers, which was forcing increased collaboration between projects, something that was difficult in a competitive environment.

New trend in energy funds

Yield companies (yieldcos) have become a notable trend in renewable energy funding internationally.

Companies typically spin out their operational renewable assets into a separate entity and list it on a stock exchange. According to Forbes magazine, the sale of electricity from these assets – including to utilities such as Eskom through long-term power-purchase agreements – provides steady cash, which is distributed by dividend payments.

These companies can also provide tax advantages and allow investors to isolate cash flow generated by these assets without exposing them to the rest of the parent company’s business.

Yieldcos listed in 2014 include TerraForm, which belongs to United States solar power giant SunEdison, and Abengoa Yield, which belongs to Spanish renewables firm Abengoa.