The meaning of the word “family” is queer to me.

Semiotically I know what the word is supposed to signify. Semantically I know what its heteronormative conventions denote. Its symbolism pervades popular representation.

The glamorised view paints the traditional family home as a stable and nurturing environment; a safe haven in which the close-knit kin share the interests and values of the family unit. And, for me, it is within these conventions that its slippages lie.

For others there can be as much meanness as meaning in the notion of family. Contemporary theorists, including Wilhelm Reich, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, have variously argued that the authoritarian patriarchal family is the locus of fascism.

The mean streak that underpins the social reproduction of the conjugal family belies its much-lamented demise. Much of this dissolution is popularly blamed on men and women “trading places”, as it were.

The entrenched typologies of traditional parental roles have now given way to the understanding that mothers and fathers both occupy multiple contradicting social and emotional subject positions that go beyond the binaries of caregiver/breadwinner, present/absent, powerless/powerful and good versus bad.

Whether in the workplace or in the bedroom, the undoing of fixed prescribed gender roles represent a crisis of identity and power for the modernist family unit. And patriarchy does not suffer defeat gaily. In spite of the backlash against the so-called postmodern family, the nuclear family is being replaced by alternative family structures that are determined by a myriad social conditions, associations and affiliations – and its worst enemy is love.

In a globalised world, few marriages are still arranged for economic, social or political gain; hence procreation, for the purpose of producing an heir, has ceased to be a primary function of matrimonial unions. We choose our partners based on love and mutual attraction.

According to historian and family studies researcher Stephanie Coontz, the increased role of love highlights the societal shift towards the importance of emotional fulfilment in our intimate relationships – a shift that undermines the foundations of the Oedipal family structure.

We are moving beyond the notion of the family as institution, bound by blood and governed by social code, towards understanding the family as a negotiated relationship. The outmoded rituals of belonging are giving way to meaningful connections based on consensus and caring.

Family, not by blood or marriage, but rather as a bond of choice and, in other instances, necessity, has become the domain of pluralist interrelationships and identity positions. It also provides space for, among other things, the emergence of new forms of gender expression.

This does not represent a simple deconstruction as much as a complicating adding-to – an entanglement of multiple relationships, subject positions and personas that make up complex collective narratives. This is not say that we are free from the textual relations and structures of hyper modernism. We are still framed by our cultural heritage, by our history and laws still in the process of being rewritten and the language we use, both colloquial and prosaic – all these contain the echoes of our social, political and private relationships and agency.

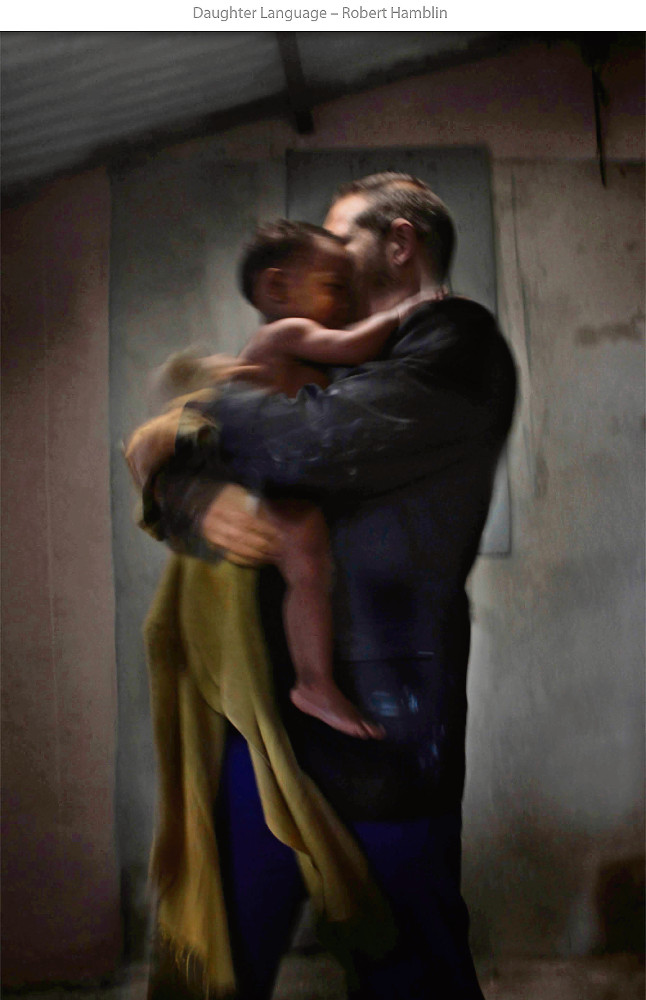

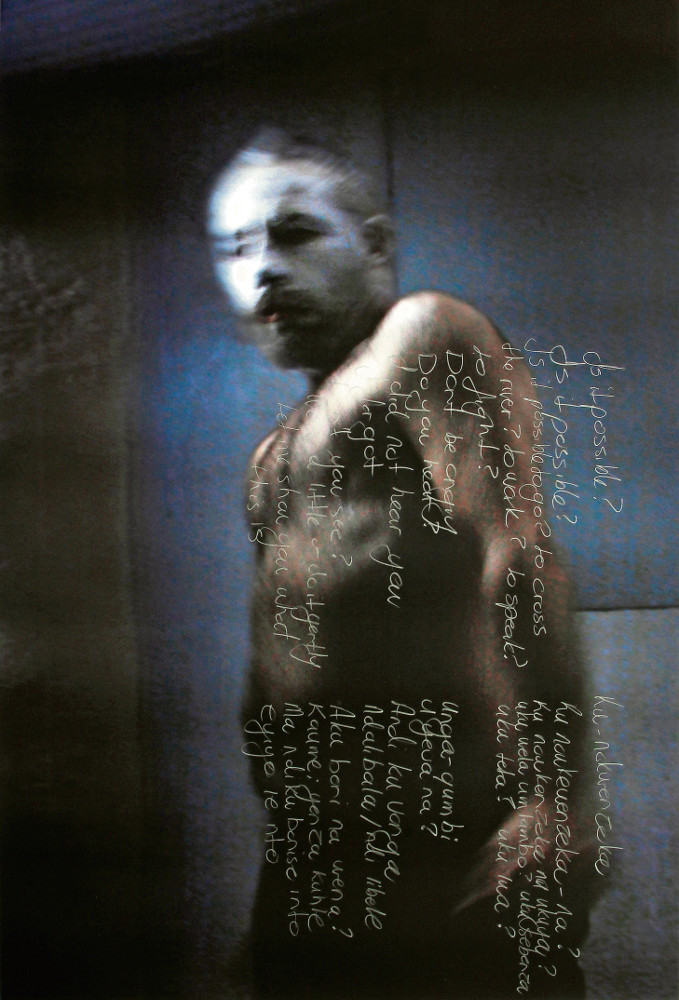

Acutely aware of his own agency and the visual and textual implications his race and gender positions represent, Robert Hamblin negotiates fatherhood and transracial adoption in a series of poignantly personal works. He transcribes the banal statements and elementary commands of a British missionary English/isiXhosa phrase book on to portraits of his own family.

This is the nervous hand of a doting father, conflicting subtle violence on to a thin, precious surface in his desire to protect his daughter from bias by exposing the structural brutality of everyday language. Through this act the artist renders visible his own paternal anxiety, as though in an attempt to exorcise the meaning from the words and render impotent the violence of language itself.

The violence is deflected by the unfixable nonstatic identities re-presented – constantly fleeting, slipping out of focus, refusing to be fixed in the gaze.

The text is suspended in the liminal space between the viewer and the subjects of the photographs. It is not a barrier to our reading of the work in the way that another language might be; instead, it provides a textual context for the decoding of the subject positions and interrelationships in the images.

Hamblin’s series of works for Daughter Language is an intimate depiction of personal-political representation, corporeal relationships and spiritual relations in the artist’s family. He invites us into a private space in which his loved ones perform intimate rituals. We, the viewers, are voyeurs catching glimpses of their intimate interactions and personal interrelations. How we read these will depend on our own experience and understanding of family.

Richardt Strydom is an artist and creative and visual communicator. This text is an edited extract from the catalogue to Daughter Language, an exhibition at Lizamore & Associates Gallery, Johannesburg, until July 25