Chéri Samba's La Vraie Carte du monde.

There is a tradition in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, that artists hang their paintings on the outsides of their studios, for the whole world walking by to look at.

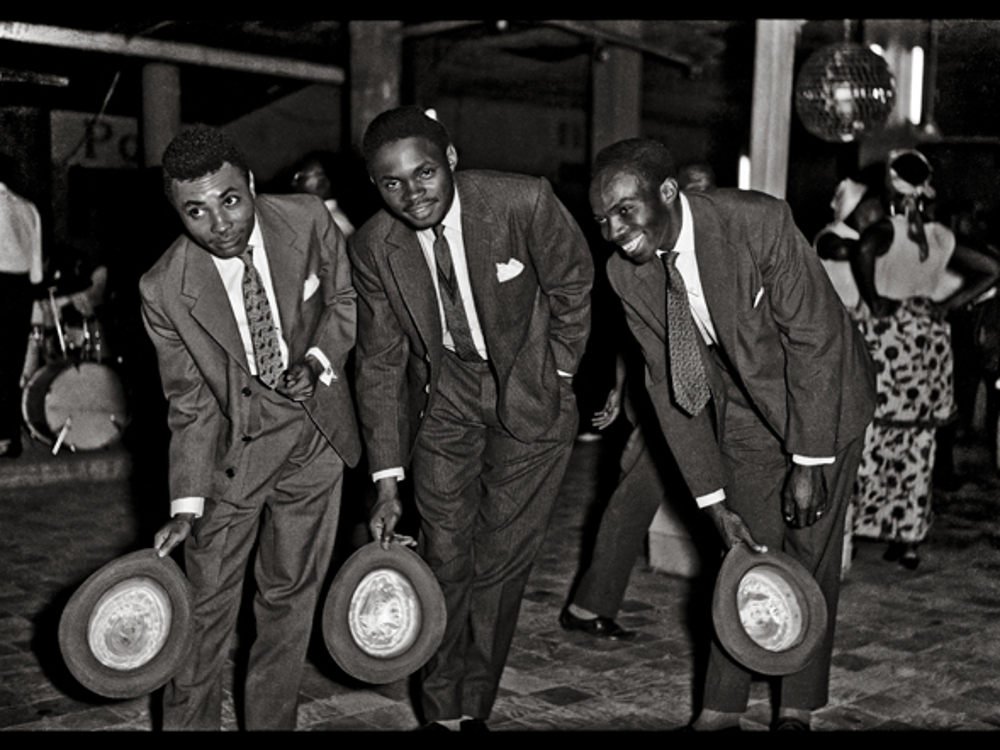

Some paintings reflect the very streets where they hang – bars filled with music and dancing, streets overcrowded with rusting cars and elegant sapeurs strutting down the pavements, bejewelled and bedecked in flamboyant outfits. Others depict a utopia, a vision of the DRC that has left behind the conflict, poverty and corruption of the past century.

Almost all are steeped in politics. It is these paintings, and other artworks stretching back 90 years, that are to form the first ever retrospective of art from the DRC. Opening on Saturday at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, the expansive show in corporates 350 paintings, photographs, sculptures and comic books from 1 different artists.

Most of these works have never been displayed internationally, having sat among private collections in Belgium, France and Switzerland, while others were dug out from colonial archives in Brussels and a few brought over from Kinshasa, direct from the artists themselves.

The exhibition may have taken just one year for curator Andre Magnin to put together but it has been his passion project for almost 30 years,having travelled back and forth to the DRC meeting and championing many of the artists now displayed. With more eyes than ever turned to the African art world, and the recent rise in African art fairs in cities such as NewYork, London and Paris, Magnin, who is the world’s foremost expert on African art, said the time felt right to finally work with the Fondation Cartier to realise his vision.

Jean Depara, Untitled, c. 1955 – 1965 (Fondation Cartier)

“People see the DRC as just this country of war and death and suffering but look around – these are such beautiful works filled with such colour and humour and sensuality,” said Magnin, standing before the Popular-styl paintings of Pierre Bodo.

“I want this exhibition to widen people’s perceptions of the country, show not only how beautiful, but also how diverse and how political the art has been over those many decades. I have been wanting to do this show since 1987 but it is only now that the time felt right. “The exhibition itself works backwards, beginning with the contemporary work of some of the younger artists painting in the capital today and ending on a series of “precursor” paintings: primitive watercolours dating back to 1926 that had lain forgotten in the depths of the Library of Brussels archive, until they were recently rediscovered by Magnin.

Among the newer works are a collection of photographs by Kiripi Katembo that depict the city of Kinshasa reflected in the dirty water that covers the streets, offering a certain poetry to the chaotic and polluted streets of the capital. Another series, by Sammy Baloji, superimposes photos of traditional Congolese tribes taken on a Belgian expedition in the late 1800s onto watercolours of the country, painted by a Belgian artist during colonial times – a pointed comment on the legacy of colonisation.

Also on display are comic books of Papa Mfumu’eto, who between 1990 and 2000 produced the most popular bande dessinée (comic strips) in Kinshasa.Though they were fictional, they drew from everyday life and the corrupt politics of the Mobutu dictatorship and at their peak were more popular than the daily newspaper.

An elusive figure, Mfumu’eto made his first public appearance in seven years to visit the retrospective in Paris. Speaking to the Guardian, he explained how he had become drawn to the medium of comic strips. He said: “My five older sisters died before turning five and then I came along and my mother was incredibly protective of me.I wasn’t really able to play with other kids because my mother was afraid of losing me like she lost my sisters.

“I felt very isolated and anonymous in terms of the world around me and the comics came to me as a way of escaping that. The comics brought people to me – they followed the stories and wanted to know what I would create next.”

His first comic, which depicted Mobutu as a boa constrictor who swallowed things and threw them up again as money – still the most popular comic ever sold in Kinshasa – can be seen in the exhibition, alongside numerous others produced over the decade.

Monsengo Shula, Ata Ndele Mokili Ekobaluka, (Tôt ou tard le monde changera), 2014

Mfumu’eto often responded to the wishes of his readers, and when Mobutu died in exile in Morocco in 1997, the artist illustrated him impregnating a woman in hell and having to burn there forever. However, making critical statements on politics in the DRC, even in the format of art, can often be a dangerous occupation. Mfumu’eto said he had& been threatened by the authorities about his comics, while Pierre Bodo, another Popular artist and evangelist priest whose paintings feature in the exhibition, died last September under allegedly suspicious circumstances.

Most artists, however, have continued regardless. One of the most internationally renowned Congolese artists in the exhibition is Cheri Samba (58) whose works have been shown at the Pompidou in Paris as well as at MoMA in New York and at the 2007 Venice Biennale. Having begun life asa billboard painter in the 1970s, he went on to pioneer the Popular style of art, bright, eye-catching works which focused on everyday life and often incorporated text.

“With my paintings I want to captivate people and I want the messages of my paintings to be direct,” Samba said. “I direct my work at the leaders and I want to use my paintings to talk about subjects they may have forgotten but are important to the people. My paintings inspired by daily life and for me, the meaning of Popular art is where people of all milieu can recognise the themes, the topics, the subjects that I am treating.

“This was created as art for the people. I believe everyone on earth has a mission and I believe that God gave me the tools to paint and speak my messages through my paintings.”

Figures from Nelson Mandela to Barack Obama crop up in his paintings, though one of the most powerful works on display in the retrospective is apiece called Little Kadogo, I am For Peace, That is Why I Like Weapons.

It is a portrait of his son dressed as a Congolese child soldier, palms up in surrender and looking directly out at the viewer. “I can’t separate my works from politics and I don’t think I ever could,” said Samba. “Yes my work has got me into difficulty, I have been stopped by the authorities but it has never gone any further than that and I don’t care. It will never stop me from painting.”

Art, said Samba, was everywhere in Kinshasa, from the posters on the streets to the facades of people’s houses. Now, more than ever, the art scene in the city was thriving, he said. He was heartened that a new generation had taken on the mantle of Popular art and that it was now being seen beyond the city and country’s borders. Indeed, Samba said he would continue to paint as he had always done.

“For 40 years I’ve always been doing the same thing in my paintings, particularly in terms of the message,” he said. “The only thing that has changed is the grey hair in my beard.”