People living close to the Vaal Dam suffer from diarrhoea and the long-term effects of mining and industrial pollutants include cancer

“Let’s chase the shit!” The statement comes with a wry chuckle on a weather-beaten face, attempting to downplay the seriousness of the situation. Peet Schabort is in search of the next sewage discharge in his hometown of Deneysville.

Sitting on the bank of the Vaal Dam, next to its wall, the town is being overwhelmed by streams of human waste. The ordure is not hard to find. Flocks of birds congregate around lakes of sewage. The murky water is bordered by dark green grass – in stark contrast to the yellow grass that dominates the northern Free State in winter.

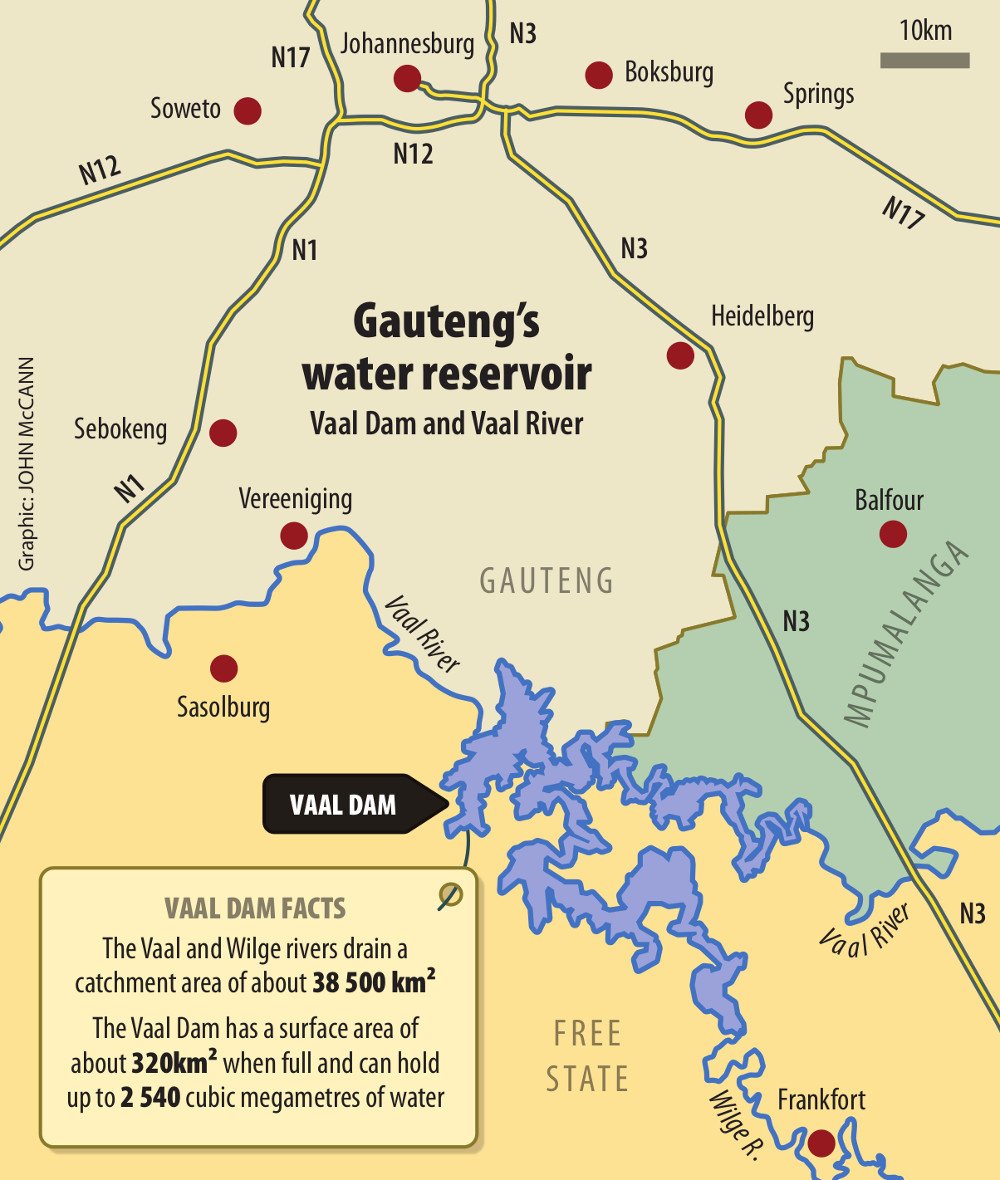

Built in the 1930s as a job creation programme during the Great Depression, the dam’s billion cubic metres of water supply most of Gauteng’s drinking water. It is also a catchment for rivers in Gauteng, the Free State, North West and Mpumalanga – to which it supplies irrigation water.

There is an adage here: “Where there are herons, there is shit.”

At fault are the town’s two sewerage pumping stations and the wastewater works that should be cleaning that waste. But it was built for a town of 4 000 people; four times that number now live in the area. The 2012 Green Drop report into the treatment works said they were running at 200% capacity. A 2014 water affairs inspection found “the plant design capacity is 2.59-megalitres a day but it is operating at almost 100% over capacity”.

Emergency treatment

Liquid chlorine was used as an emergency treatment when spillages occurred – but the municipality could not afford this and applied for funding to upgrade the plant.

The treatment plant is on empty grassland between the adjoining township of Refengkgotso and the two-storey municipal waste dump. It was built without environmental permits. When the Mail & Guardian arrived, the previously stationary aeration arms of the plant’s flotation ponds suddenly started working.

The blue of the Vaal Dam is visible a kilometre from the top of the dump. Yachts sit anchored at the marina, obscured at times by the stinking smoke coming off the dump.

A rusted red tractor pulls into the plant to dump waste collected from homes still using the bucket system. The pungent smell of sewage throttles every other aroma.

Locals say only a fraction of waste makes it to the works. “Basically, the plant now appears to comply with legislation because all the extra sewage is not getting to the plant,” says Irene Main, chairperson of the nongovernmental organisation, Save the Vaal. Standing next to the drunkenly skew and open gates to the plant, she hands us her pile of correspondence with government departments – so thick that her hand cannot grasp around it. “Nobody is taking responsibility for the sewage. Apparently having diarrhoea and E.coli levels at dangerous levels is acceptable.”

Solids and liquids

A few hundred metres from the plant, the pipe carrying sewage to it is leaking into people’s township homes. Solids and liquids bubble up and flow downhill.

None of this seems to upset Johannes Tladi. With a welcoming smile he steps across the blocks in his yard enabling him to walk across the sewage. But then his mood changes: “This really isn’t good. How are we supposed to live like this?”

His supper is cooking in a three-legged pot, which keeps sinking into the saturated earth. Things are worst in spring when the heavy rains come – the lake of sewage in his yard has been there since November, he says.

A manhole cover for the pipe that heads towards the sewerage works continually leaks into his yard. “We ask our municipality but they do nothing,” he says. “Maybe when it is election time they will come and promise to do something.”

When the treatment works is pushed beyond capacity – which locals say is on a weekly basis – it floods into nearby fields. Danie Cilliers’s farm dam is the first stop for the sewage. Green algae floats on its surface. “My fields here are all dead so I can’t grow crops, and now my cattle cannot drink the water.”

He has turned to raising wild game, which are hunted by poachers with packs of dogs. The Vaal Dam is half a kilometre downhill from his dam. When it overflows, the sewage goes straight into South Africa’s most important water source. Narrowing the peak of his khaki cap, he says his boreholes are now contaminated by the sewage and irrigation water from the Vaal is already polluted.

‘Lunacy’

“It’s lunacy,” says Johannesburg water rights activist Paul Fairall, who has been agitating around water for many decades. “We’re poisoning our drinking and farming water because nobody cares enough to stop our municipalities and companies.

“You have clean water coming from Lesotho [through the Highlands water scheme] into the Vaal Dam, and then you pollute it so much that it has to be heavily treated to become drinking water again.”

Fairall says this with a resigned tone. “But nobody is willing to step on anybody else’s toes so the pollution is not being stopped.”

Residents of townships near the Vaal have to pick their daily route through raw sewage. (Photos: Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

In the case of Deneysville, the municipality started building a new waste pipeline and an artificial reed-bed to release more waste into the dam. The reeds would help treat the water before it was released. But the municipality did not ask for a water-use licence from the water department and, in this case, the department was able to stop construction.

What water the wastewater plant does release through the old pipeline – when it does not overflow – goes into the Vaal Dam 400m away from the inlet pipe for Rand Water. This supplies drinking water to 10-million people in Gauteng. Its last annual report noted that “a number of water quality issues have been identified with regard to the current quality of the Vaal River system”. These include an increase in salinity, sulphates, microbiological pollutants and dissolved solids.

Biological and chemical challenges

Rand Water says in its quarterly report released in April this year that the most significant “water quality challenges” are biological (from faecal matter) and chemical (from gold mining and industrial pollutants). It says that the majority of municipalities around the dam are in contravention of the National Water Act because they are releasing unsafe levels of ammonia and E.coli. The co-operative governance department and municipality did not respond to questions about these contraventions.

Rand Water, which monitors water quality on behalf of water affairs, also avoided answering questions this week. The results of its research are given to local water forums. In most cases the levels in the dam exceed safe levels as prescribed by the World Health Organisation.

The pollutants in the dam can lead to cancer, birth defects, skin problems and brain damage, in the long term. But in Deneysville the short-term effects – such as diarrhoea – are in abundance.

“We are creating a breeding ground for super diseases,” says Andre Johnson, who lives downstream from the sewerage plant. He recently caught fish in the Vaal Dam that were covered in sores. “Things are becoming strange.”

They pour excuses on troubled waters

The Vaal Dam was built to catch and supply water to the economic heartland of South Africa. But it has become ringed by heavy industry, mining, farming and human settlements. Each releases its own pollutants into the dam.

The drinking water provider to Gauteng, Rand Water, has to purify the water it sources from the Vaal Dam. Everyone else – from farmers to people downstream who don’t have purification facilities – has to use polluted water.

The water affairs department’s policy on this is dubbed “fixing pollution with dilution”. When the water becomes too polluted, more water is allowed to flow through the Vaal. This is despite South Africa being the 30th driest country in the world.

Solutions are supposed to come from catchment management agencies. These bring together anyone using water to work out issues of sharing and stopping pollution. But, despite being mooted a decade ago, most of these are still not operating.

Instead, users meet at water forums. The minutes from several of these around the Vaal Dam point to municipal wastewater treatment plants as the biggest headache when it comes to dirty water.

Water affairs says in its annual reports in the 2000s these plants released 200 000 tonnes of salts into the dam each year. Industry added 280 000 tonnes more, which resulted in levels five times the World Health Organisation’s recommendation.

A water treatment plant.

The 2010 minutes of the Blesbokspruit water forum, in the Vaal Dam’s catchment area, come with quarterly water quality status bulletins for the whole area. Recorded by Rand Water, almost every reading along the dam and in its two subsidiary rivers indicates dangerously elevated levels of ammonia, chloride, nitrate, phosphate, sulphate, E.coli and other pollutants.

In often heated discussions – recorded in the minutes – exasperated government officials argue with each other about the causes of pollution and ways to stop them. When questions are raised by civil society, polite answers that allude to overriding political concerns are given.

In a meeting last year one water official said: “All we can do is keep diluting water in the Vaal as there is little will to really tackle the problem: the polluters … especially since local government is such a big source of that pollution.”

The lack of government co-operation is continually repeated. In Deneysville, 2 500 new houses are being built without a corresponding upgrade to the already broken wastewater treatment system.

Old mines south of the dam have been allowed to continue polluting the Wilge River, which brings water from Lesotho to the Vaal. These are linked to several large bird and fish die-offs. New gold and coal mines have been given prospecting licences by the mineral resources department along the dam’s eastern shore. The mines south of Heidelberg are going ahead despite opposition from Rand Water and water affairs about being in a critical water catchment.

Sewerage plants, the worst polluters, fall under the co-operative governance department. Municipalities, such as Deneysville, are given funding to build and maintain their works. The water department gives them a licence to do this, on condition that they release clean water back into local water sources. These sources are owned by the department, which acts as the custodian of all the water in the country.

To track these plants, water affairs used to release the annual Green Drop report. The last one said six plants around the Vaal Dam were releasing “noncompliant” water, in other words, illegal water. But an official in Pretoria says: “Our hands are tied. This gem [the Vaal Dam] in our water system is being destroyed by municipalities, but what can we do? Government departments are not allowed to take each other on.”