Mammography is a method for early detection of breast cancer.

For many women, it is one of their worst nightmares: a lump. The first reaction when they find one in a breast is panic, “oh no, I have breast cancer”. Although not all lumps are cancerous, in South Africa breast cancer is one of the most common causes of death in women. Approximately one in 12 white women and about one in 49 black women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime.

But the low incidences in the black population could be misleading as a result of fewer cases being reported or diagnosed. This could be due to a lack of education or access to healthcare services, more especially in poverty-stricken, rural communities.

At the Division of Human Genetics, University of the Witwatersrand/National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS), we are studying genetic mutations in black South African women to try and understand what contributes to the aggressive breast cancer characteristics seen in these women. We would also like to increase our knowledge of breast cancer in this population.

Since the discovery of the field of genetics by Gregor Mendel in 1866, scientists have learnt and are still trying to learn how DNA (the hereditary material passed from parents to their children) contributes to certain characteristics and diseases.

In genetics, breast cancer is classified as a complex or multifactorial disease. This means it is the result of many genes (which are made up of DNA) that interact with each other and with the environment.

Similar complex diseases tend to cluster in a family. This is because blood relatives will often have similar genes and environmental exposures which will increase their risk for a specific or similar disease. For example, related cancers such as breast, ovarian and colon cancers will affect blood relatives because they have the same grandparents and often live in the same area.

Only about 5% to 10% of all the newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer have a strong genetic component, meaning they do not occur spontaneously but are inherited in a family. Only about 5% to 10% of all the newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer have a strong genetic component, meaning they do not occur spontaneously but are inherited in a family.

Inherited breast cancer often goes hand in hand with an earlier age of diagnosis (younger than 50), a family history of related cancers (such as ovarian or colon cancers), cancerous tumours in both breasts and male breast cancer.

In most cases, inherited genetic mutations (mistakes or changes in the DNA code) in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are responsible, but other genes have also been implicated. These two genes are normally involved in repairing damage to the DNA during processes such as DNA replication. When genes get mutations that are harmful, they change the normal function of a specific cell. It is like adding a wrong ingredient to a recipe – the entire dish is ruined. If the BRCA genes are defective as a result of mutations, they are unable to repair any damage to the DNA. This means that damage builds up in the cell and leads to the formation of tumours and disease.

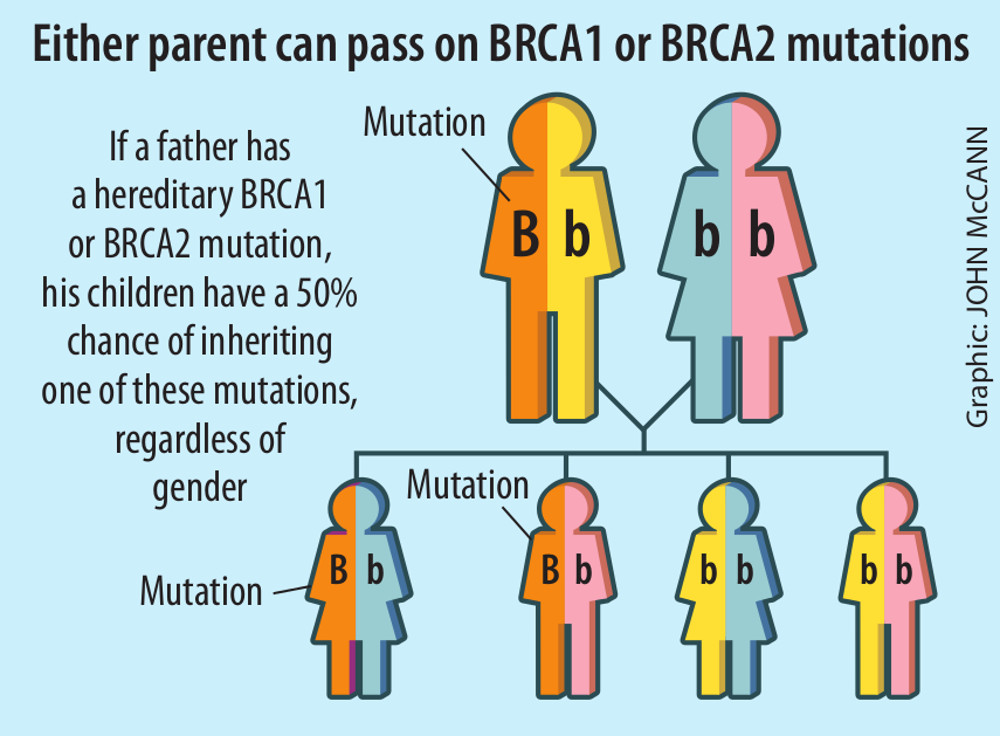

For a person to develop inherited breast cancer, they have to inherit one mutated copy of either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene from at least one parent.

Women with mutations in one of these genes have an 80% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer.

This means that 80% will have breast cancer and the remaining 20% will be free of breast cancer for their entire life. In a much publicised example, the actress Angelina Jolie lost her mother to ovarian cancer. Jolie discovered she had an 87% risk for breast cancer and a 50% risk for ovarian cancer.

This was a result of a defective BRCA1 gene she inherited from her mother. She elected to have a double mastectomy (removal of breasts) and had her ovaries removed to prevent later diagnosis of breast or ovarian cancer. This shows that even though relatives may inherit the same defective gene, they may not all develop the disease.

Unlike in the white population where there is a better understanding of inherited breast cancer, in the black African population, the understanding is limited. Also, inherited breast cancer in South African black women – and their counterparts in other African countries and in African-American populations – has some unique features. Black women are often diagnosed with breast cancer at even younger ages and their tumours are particularly aggressive.

Individuals of African descent show high genetic diversity. Black South African populations in themselves differ in their genetic makeup. This makes it difficult to study diseases like breast cancer, where many mutations in different genes have been reported to increase breast cancer risk in individuals. So, identifying population-specific mutations in African populations could help us to diagnose inherited breast cancer even earlier.

Founder mutations – which tend to happen when a small group of individuals migrate away from a large group to a new area – have been identified in different South African populations for different diseases, and are specific to those populations.

For instance, we know that in South Africa there are founder mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes in the Xhosa, mixed ancestry (so-called “coloured”) and Afrikaner populations. Identifying founder mutations will help us to do genetic testing that is specific to each population group.

Our previous research identified BRCA1/2 mutations in black South Africans who carry a high risk for inherited breast cancer.

Only about 10% of the people who came for genetic testing have inherited mutations in one of their BRCA genes. So what is contributing to the breast cancer burden in the remaining 90% of the patients?

We aim to identify new and pathogenic mutations in other genes (not just the BRCA genes) and use a next-generation sequencing technique to study these mutations.

This technique looks for and identifies mutations in different genes. Next-generation sequencing techniques can study multiple genes simultaneously and reveal many mutations in a single test, which is cheaper and saves time.

Identifying other mutations that increase black South Africans’ risk of breast cancer may help to improve future genetic testing, genetic counselling and management, and treatment options.

This should help to reduce ill health and deaths in black women.

Reabetswe Pitere attends the University of the Witwatersrand.