Although the proposed amendment is a good start, the department has missed an opportunity to transform the way executive compensation is determined and justified in South Africa. (Reuters)

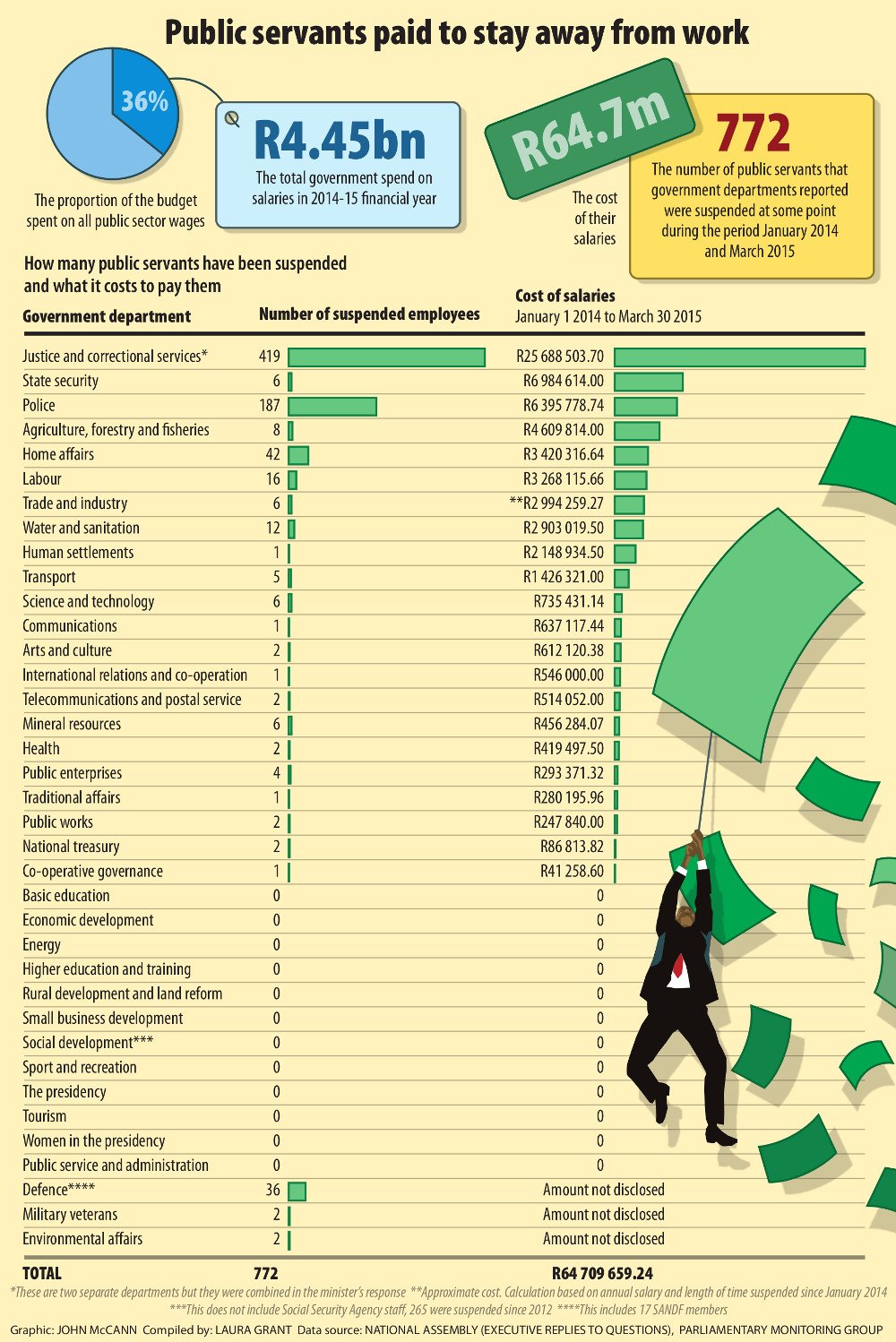

The salaries of public sector employees eat up nearly 40% of the government’s budget. Curtailing “bloated budgets for employee compensation”, as the treasury phrased it in its latest budget review, is an important way to contain costs. But government departments spent nearly R65-million in the past year on the salaries of 772 suspended employees.

Drawn-out, expensive suspensions are also fairly common. Last year the Cabinet approved the creation of a pool of labour relations and legal experts to help clear the backlog of disciplinary cases.

Dumisani Nkwamba, spokesperson for the department of public service and administration (DPSA), under which the new pool falls, said it has “begun to identify all departments that require urgent intervention and is interacting with them accordingly.

For Michael Cardo, a Democratic Alliance member who formerly served on the portfolio committee on public service and administration, “it became clear that suspension on full pay was a creeping phenomenon in the public service”. He decided to find out the extent and cost of these suspensions by posing a parliamentary question to all the ministers.

By April 2015, 37 government departments had submitted written replies containing varying levels of detail about the employees who had been suspended during the period January 2014 and March 2015 (See graphic).

Three departments

Nearly 80% of the 772 suspended employees worked in just three departments: justice, correctional services and the police. The totals for justice and correctional services were combined in the parliamentary response, which can probably be explained by the fact that, although they are two separate departments, since last year’s Cabinet changes they have fallen under one minister.

The departments did not reply by the time of going to press to a request to separate out their individual suspension numbers, or explain why the number of suspensions was so much higher than other departments.

Together justice and correctional services spent R25.7-million paying 419 suspended employees – 40% of the total spend of all the departments and more than half of the total number of suspended staff.

Add to that the R17 357 233 the National Prosecuting Authority paid out to the former national director of public prosecutions, Mxolisi Nxasana, and it has been an expensive year for the minister of justice and correctional services.

The correctional services department reported that one senior manager in KwaZulu-Natal, was suspended on full pay for more than two years before he was dismissed, reportedly for dereliction of duty and insubordination.

60 days

In terms of section 7(2)(c) of the Disciplinary Code and Procedures for the Public Service, prompt investigations must be conducted and disciplinary hearings must be held within 60 days from the date of suspension.

“Government’s policy on disciplinary procedures is that cases need to be finalised within 90 days,” said Nkwamba.

But often, 90 days pass without any disciplinary action being taken.

For example, the state security department, which is ranked second on the list for the size of its suspension salary bill, reported a R7-million salary bill for just six suspended officials. That’s an average of R1.16-million each for the period January 2014 to the beginning of 2015, roughly a year.

The six employees, none of whom was named, had been suspended before January 1 2014, according to the minister’s parliamentary reply, which means they had all been suspended for more than a year, although it’s unclear exactly how long they have been suspended for.

Expensive salary bill

The department of labour, which is ranked fourth on the list for its expensive suspension salary bill, had 16 ongoing suspensions. One employee, advocate Nkahloleng Phasha, the chief director of legal services, was paid his R82 346 salary for about 41 months before he was acquitted and returned to work, which means he received R3-million while not working.

“What is quite clear is that the ANC-run government has failed to implement proper procedures to ensure the completion of disciplinary processes within reasonable timeframes, and therefore tacitly allows officials to be on suspension endlessly, with full pay,” said the DA’s Ian Ollis in a statement in December 2014 in response to Phasha’s prolonged suspension.

Click here to view the responses to parliamentary questions

In March, the 15 other suspended labour department employees were reportedly costing the department just over R300 000 a month in salaries, according the department’s parliamentary answer.

Four of the 15 employees had been suspended for more than a year and all but one had been suspended for longer than 60 days.

The department of trade and industry has spent R2.8-million since January 2014 paying suspended staff, the bulk of which (about R2-million) went to two senior officials – a chief director and a director. As of March they had been suspended for 374 and 283 days respectively.

Central database

Last September, the DPSA announced it had established a central database of disciplinary cases in the public sector to speed up their resolution.

“In future, all cases in all spheres of government will be registered so the department is able to monitor their life cycle – who has been fired, who has been suspended and who has received a warning – on the system.”

The department also said it had developed sanctioning and precautionary suspension guidelines that are “intended to ensure that employees are only suspended in appropriate circumstances”, which was due to go before the Cabinet for consideration.

Figures on the number of disciplinary cases, according to the National Labour Relations Forum, for the fourth quarter of 2014/15 were 1 239 cases in national departments, with 765 of these cases finalised within 90 days, 64 finalised outside of the 90 days, and 410 cases still pending, said Nkwamba.

In the meantime, suspensions appear to be seriously affecting the functioning of some departments.

State of disarray

The department of military veterans, for example, put its director general, Tsepe Motumi, and deputy director general of corporate services, General Lifeni Make, on “special leave” on April 22 2014 to “allow for an investigation to be conducted on matters arising from the internal audit”, the government said. Motumi was reportedly issued with a final warning.

But then in October, the minister of defence and military veterans, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, told Parliament she was unable to table the annual report, financial statements and audit report of the department on time because the department’s chief financial officer was on sick leave and then placed on “special leave” during the audit.

In March, IOL reported that the standing committee on public accounts cancelled its hearings into the department because its financial controls were in a state of disarray.

Only 12 out of the 37 departments reported in March that they had had no employees suspended on full pay since January 2014.

“South Africa’s public sector has grown – one is twice as likely to be employed in the public sector today, as 40 years ago – with little perceived improvement in service delivery, law and order, and administration,” wrote Nazeer Essop of Deloitte in an article about managing the public sector wage bill.

“Our Brics partners [Brazil, Russia, India and China] spend on average 25% of their total government expenditure on salaries; by contrast South Africa spends approximately 40% of its budget on salaries, or R450-billion annually.”

Significant cost savings

Essop added that the government could make significant cost savings by improving its human resource processes.

“Many employees are placed on suspension with full pay for anywhere up to two years while disciplinary procedures are followed. By reducing red tape and streamlining the human resources processes, the savings on the wage bill can be substantial,” he said.

The treasury knows that the patience of taxpayers is being taxed. “Improving the quality of public spending, combating corruption, and eliminating waste and inefficiency are vital to maintaining the goodwill that sustains revenue collection,” it stated in the Budget Review 2015.

“Too many people milk the system for all it’s worth,” said Cardo. “And the fact that public servants are suspended on full pay, sometimes seemingly endlessly, with no sense of urgency on anybody’s part to put a stop to the situation, typifies that.”

Said Nkwamba: “The DPSA is working with all national and provincial departments to improve discipline management and ultimately reduce the number of suspensions.

“We will continue to analyse trends on the management of discipline, provide solutions to challenges faced and assist with human resource and training deficiencies in the public service.”