COMMENT

They were two cricketers, the one famous for his talent, aggression and belligerence at international venues such as Lord’s, Trent Bridge, Newlands, the Wanderers and in India, the country that hosted the first post-isolation South African tour. The other was a man who put his life into the total isolation of South African sport as a necessary weapon for political change.

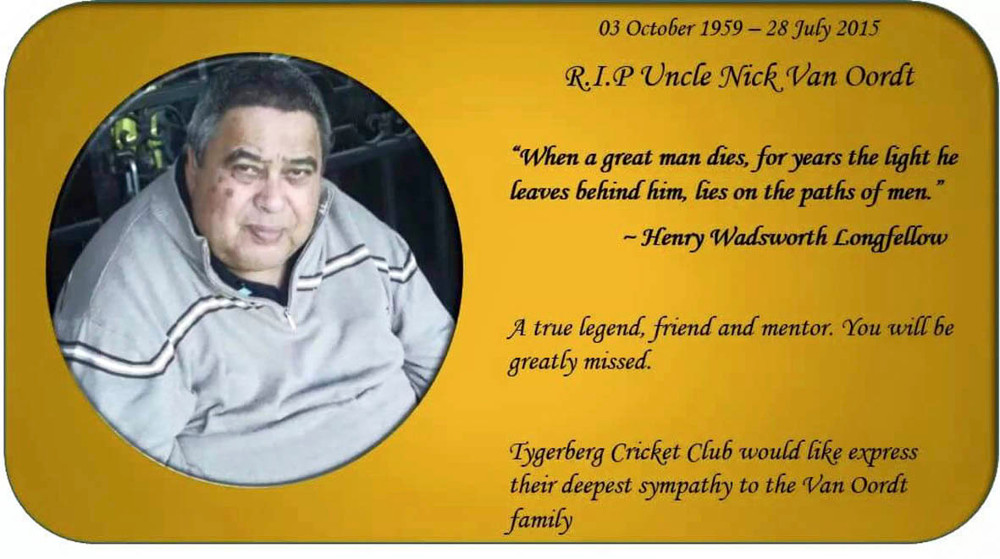

Clive Rice and Nico van Oordt died in the same week. Not surprisingly and befitting for a player of his calibre, the print and electronic media gushed with tributes for Rice.

Van Oordt’s death barely caused a ripple. But the many people whose lives he had influenced took to the social media to pay homage to this big man.

Both were born and raised in another country in another age. Rice enjoyed all the trappings that white minority rule gave those who were not black. He played in what the government, mainstream media and the majority in white society regarded as the official national organisation for cricket. His sports world only had the best when it came to facilities, equipment, sponsors with fat pockets and excellent media coverage.

Rice was on first name terms with leading (white) cricket writers and sports editors. His message, whether he knew it or not, was that life is good in white South Africa if you were white. As far as I can recall, Rice did not speak out against the policies of the National Party.

He led the Transvaal team that was known as the “Mean Machine” in the Currie Cup competition, and he also became a legend in English County Cricket where he played for Nottinghamshire.

Common line

A common line running through the obituaries for Rice was what a great player he had been, how he had often stood up to (white) cricket administrators, how he had made his bat and ball do the talking and earned him the right to be classed among the best all-rounders in the world in his playing days. He was truly a great player.

It was sad, many reports said, that because of South Africa’s isolation he hadn’t been able to play international cricket. How he had been unable to test himself against the best in Test cricket. Nothing was said about the millions of South Africans who were turned into foreigners in their own country because they were black. Not a word about the opportunities they were denied to represent their country. Not a word about how they willingly endured isolation as well.

Van Oordt was legally disenfranchised. His was to be the land of deprivation, no international stage, playing cricket in a national nonracial association that was largely ignored by the white media, which somehow apparently believed that noncoverage or little reportage would squeeze the will to fight out of these unofficial sports bodies.

But they underestimated the tenacity of the South African Council on Sport (Sacos), that national nonracial organisation dedicated to the isolation of South African (white) sport.

Led by formidable characters such as the late Hassan Howa, who knew how passionately white South Africa loved international sport, and understood their need to win at the highest levels, Sacos and the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (Sanroc), made the sports world its battleground.

Its soldiers were men, women, boys and girls who dreamed of one day representing a different South Africa. They knew that they had to suffer the pain and endure in the long term if they wanted to succeed. And while some were lured to what was derided as normal sport, the majority stayed on the Sacos road. It was a road that caused those who drifted to the “official” sports bodies to be pariahs in their communities. They were criticised for being “white” while they were on a sports field and black the minute they stepped off it. Many were shunned: at school, in the workplace, in churches and mosques.

Sacos and Sanroc, astutely led in London by Sam Ramsamy, succeeded, with others, in bringing change. But they did not change attitudes or long-held beliefs. In this age of quotas and the resistance to the inclusion of “Africans” and other blacks, their dream of nonracialism still has to be reached.

Abnormal society

For people like me, it took the death of Clive Rice juxtaposed against that of Nico van Oordt to appreciate and recall once again the contribution of so many sportspeople who played nonracial sport in an abnormal society.

How sad then that not even the Proteas thought of paying tribute to Van Oordt as they had to Rice on the opening day of the second Test against Bangladesh. They wore black armbands and stood in silence for a moment in memory and respect of the democratic South Africa’s first cricket captain.

Watching it on TV filled one with regret that the name Nico van Oordt was not remembered. It was because of the sacrifices of people such as him that the likes of Hashim Amla, JP Duminy, Vernon Philander, Makhaya Ntini, and lest we forget, Dale Steyn, Shaun Pollock, and, indeed, Rice could play international cricket as the representatives of a liberated South Africa.

But such are the effects of amnesia and the airbrushing of history that few of the tributes to Rice mentioned apartheid, and the benefits that this abominable political ideology conferred on talented people such as him. Indeed, to many white people, he was a hero in another political order – a country that expected its sporting heroes not to take a stand against apartheid. To that country Van Oordt was not a hero, he belonged to a group of activists who mixed politics and sport.

But to people like me, he was a hero, a giant in more ways than one, a person who believed that there would be a better future. He lived to enter a new world, to vote as a free man, and to see Rice captain a real and fully representative South African cricket team, one that he as a player and administrator could identify with.

Dennis Cruywagen is a journalist and political commentator.