The oversupply of crude has persisted since July last year and Africa's oil and gas industry is not immune to the effect of this global oversupply.

The decline in the oil price has plunged Africa’s oil and gas industry into dire straits, a situation exacerbated by factors such as uncertain regulation, corruption and the prospect of political and social instability.

It is a particular burden on those economies most reliant on the industry for revenue, and could have far-reaching socioeconomic results.

The oversupply of oil has persisted since July last year, when the price of Brent plummeted from more than $110 a barrel to less than $50 in January this year, and again in recent weeks.

The price has, as expected, hurt the natural gas fracking boom in North America, with higher-cost producers going out of business. According to the oil-fields services company, Baker Hughes, on August 7, there were 1 024 fewer rigs in operation in the United States than in the previous 12 months. The current US rig count is 884.

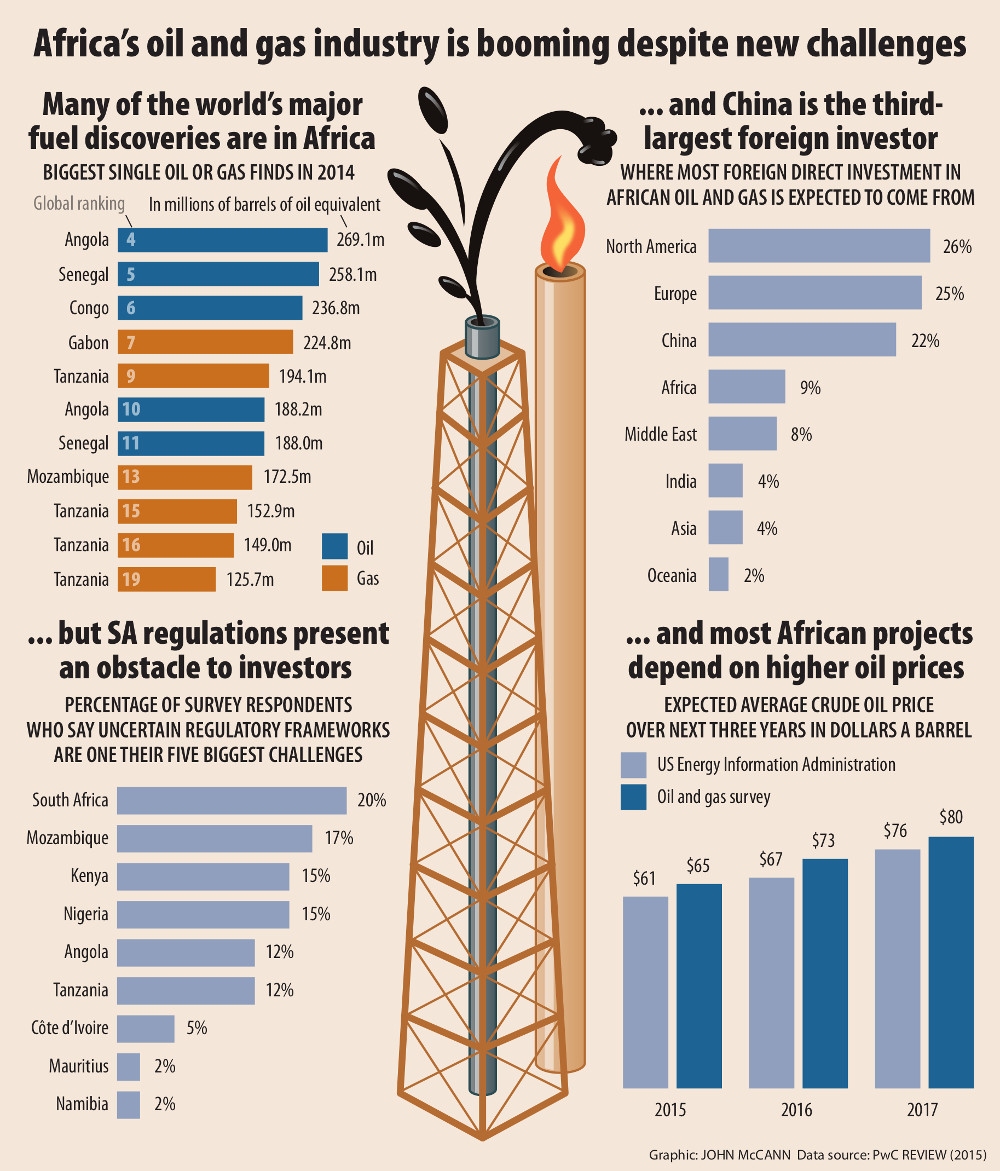

Africa’s oil and gas industry is not immune to the effect of the global oversupply. The recently published PwC Africa Oil and Gas Review 2015 found that respondents to the survey were suffering because of the reduced prices, and were plagued by issues such as regulatory uncertainty and corruption.

But it is the price of oil and natural gas that is having the biggest effect on the industry, with more than 70% of respondents saying it will affect their business over the next three years.

From June 2014 to June this year, the price of crude dropped about 48%, and the price of natural gas 31%.

In recent years, Africa’s oil and gas sector had played a crucial role in the economic growth and development of the continent, PwC said.

And sustaining growth and development on the continent hinged on the ability of countries to monetise their natural resources.

Oil revenues also make up a significant part of the gross domestic product of many African countries. In 2014, Africa produced 8.2-million barrels of crude oil a day, and more than 76% of it came from Nigeria, Algeria, Egypt and Angola.

PwC said those whose economies were not well-diversified, such as the Republic of Congo, Gabon and Angola, would be hit hardest and they might have to adopt austerity measures and revise their budgets.

For example, the African Development Bank expects Angola’s economic growth to decelerate from 4.5% in 2014 to 3.8% in 2015. All of the PwC report’s respondents from Angola, where oil accounts for 70% of all revenue, rated the price of oil as having the biggest effect on business over the next three years.

“The risks to the Angolan economy are not just limited to the implementation of austerity measures. A reduced budget could mean the government is not able to pay civil servant salaries and a reduction in the provision of social services. This could increase the risk of social instability,” the report warned.

The lower gas price has negatively affected gas producers, in particular the fledgling East African economies looking at monetising their assets in the next three to five years.

Legislation

Apart from the volatile resource price, African oil and gas players in Africa rate regulatory uncertainty as the biggest hurdle expected to affect their business in the coming years.

“Roads and pipelines can be constructed. Local content can be managed. People can be trained and developed. Clear and attractive legislation and regulation, however, can only be influenced,” PwC said.

“Without it, companies are willing to simply walk away in favour of working in other regions of the world that do offer this fundamental prerequisite … Almost every aspect of the business comes with uncertainty. Legislation cannot be one of them.”

Yet in many African countries it currently is. More than 80% of Tanzanian respondents regarded regulatory uncertainty as the top challenge facing the industry. In Nigeria, Kenya and Angola, more than 50% of respondents saw it as a significant impediment to growing the business in Africa.

Although 53% of respondents said that local content and regulatory policies had no effect on their project investment decisions – similar to the survey findings from previous years – an increased number of companies had to revise their project specifications because of local content requirements, recording a 5% increase from 2014.

The largest number of respondents who listed regulatory uncertainty as one of their top five concerns when it came to the development of the oil and gas industry was in South Africa.

“Investment in South Africa has stalled for another year as lawmakers work to approve amendments to the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act [MPRDA],” PwC said.

“Companies have put spending on hold until there is clarity on the Act, which included a new clause which entitles the state to a 20% free carry in exploration and production rights, and an uncapped further participation clause enables the state to acquire up to a further 80% at an agreed price or under a production sharing agreement.”

South Africa’s shale gas resources are considered to be among the top 10 largest in the world and it is reconfiguring its policy to position itself as a powerful energy player. Apart from the MPRDA, this policy includes the Gas Utilisation Master Plan and the Competitive Supplier Development Programme.

“South Africa’s uncertain regulatory framework for the oil and gas industry is largely the result of unclear and overlapping mandates between the government and government departments,” PwC said.

“[In Africa] the stricter regulation could stimulate growth within countries by providing structure and clarity but, overall, they could also inhibit Africa’s growth and development.”

Corruption

Concern about the effect corruption has on the oil and gas industry remains in the top five challenges identified by the respondents. More than 43% said fraud and corruption would have a severe effect on their businesses over the next three years.

“Government officials continue to be implicated in a number of fraudulent activities across the continent. Bribery and procurement fraud remain some of the top types of economic crimes in the broader energy, mining and utilities sectors, as revealed in the PwC Global Economic Crimes Survey 2014. Worryingly, a considerable portion of these are systematic corruption and fraud,” the report stated.

But there appeared to be some progress on that front, PwC said. For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo last year became Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) compliant.

“The fragile political situation in North Africa continues to have an impact on production levels, which saw another year-on-year decline in oil production in the region of 22%. Libya alone, in the throes of civil war, saw production decline by almost 50%,” PwC reported.

“Despite continued insurgency in South Sudan, production has increased by just over 60% compared to 2013”, although it was still a far cry from pre-2013 production levels following damage to infrastructure.

Activism, instability and political events ranked fourth in the hierarchy of concerns in Africa’s oil and gas industry. This is the highest ranking since PwC conducted its first industry review five years ago.

“Respondents from South Africa, Mozambique, Nigeria and Kenya, in particular, expected community/social activism/instability and unstoppable political events to have a significant impact on their business,” the report said.

Emerging agility

More than 90% of the respondents expect the oil price to increase gradually over the next three years and estimated the price would remain in the range of $60 to $70 in 2015, and will reach $80 to $90 by 2017.

But most of those in the industry have modelled their projects on the assumption of an oil price higher than $80 a barrel. And many of the recent large discoveries are offshore in deep water, which adds complexity and cost to recovery.

Deflation in the oil price over the past 12 months, and the expectation of a slow upturn, has limited the potential for exploration as companies seek to cut costs. More than two-thirds of the respondents said they would look at some level of formal cost reductions over the next three years. Of those, 82% wanted to reduce costs by 10% or more.

Producers, including BP, Shell and Total, have already made moves to reduce capital expenditure through a range of measures such as instituting pay freezes, reducing headcounts, deferring or abandoning investment and even changing business models.

PwC said cost-cutting was often a knee-jerk reaction to a depressed price and warned companies against cutting in the wrong places, such as in research and development.

The dire state of Africa’s oil and industry does present opportunities for some.

A few respondents said the lower oil price would enable increased exploration and development because contractor and rig costs were lower.

PwC said these lower costs were being factored into models to identify the commercial viability of new ventures, which could provide an area for growth in the industry over the next few years.

“It is clear through our interactions that many companies are taking a different perspective on the challenges they face. They are being looked at as realities that can and must be dealt with if they wish to enter African markets,” the report said.

“This lull in activity is giving the industry a moment to make plans for the execution of large-scale projects while also formulating a strategy that will make them more competitive for the future in the new African market.

“While the industry is in a fragile state, we at PwC envision that the players who survive the downturn in prices the best will emerge as agile machines with well-thought-out plans.”