Turkish delight: 'The Most Beautiful of All Mothers' by Adrian Villar Rojas.

Just south of Istanbul, on the island of Büyükada in the Sea of Marmara, Leon Trotsky lived from 1929 to 1933, in exile and constant fear of assassination. Beyond the caved-in walls of his house is a path winding down to the sea. Suddenly, one clambers out on to the foreshore, to be faced with a pair of gleaming white giraffes, perched on plinths in the swell.

A whole bestiary stands in the water: a gorilla with a stone lion perched on its back; a bear; a rhino carrying an elk on its shoulders; a sheep is laden with a huge bundle of firewood; an ostrich wears what looks like a fur coat.

Adrián Villar Rojas’s lifesize fibreglass creatures are all burdened with other bodies, other animals made from cloth, pottery, iron, wood and terracotta. The wonder doesn’t last. It is impossible not to think of other beaches, of bodies floating in on the waves.

Elsewhere on this little holiday island, an hour by boat from the city but still part of the Istanbul Biennial, Trotsky is drowning in speeches and thinking of women and revolution at an old-fashioned hotel. A group of rackety black-and-white films by William Kentridge show Trotsky with his beard, his electrified hair and a megaphone.

Down the road, Ed Atkins’s avatar, which gets more realistic and more haggard in every digital film the artist makes, is going mad in a deserted wooden pension, its rooms a chaos of fallen plaster and abandoned bedding. He sings and sobs: “I’m sorry, I didn’t know, I’m sorry.” His distress is undercut by snatches of Elton John and Kiki Dee’s Don’t Go Breaking My Heart. After this, the room starts collapsing in a satisfyingly noisy catastrophe. Maybe it’s an earthquake.

A theatre for marine life

Don’t ask me why any of this is happening, but it does and it is brilliant. Atkins was inspired by the 2013 news story of a Florida man whose house was swallowed by a sinkhole while he was asleep. In his film, the vertical hold goes and we’re churning between floors. Atkins gets better and better, worse and worse. His work is shown on two screens on different floors of the building, among all the mess.

Out in the haze between the islands is an even stranger work. I haven’t seen it. No one has. Several fathoms under the waves, Pierre Huyghe is building a theatre for marine life. He is hoping that the bizarre, “biologically immortal” jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii will inhabit his construction, Abyssal Plain. The idea that it is here is enough.

Huyghe’s work is near the island of Sivriada where, as part of a programme to modernise Istanbul in 1911, more than 80 000 stray dogs that roamed the city were ferried to the barren outcrop, where they died of thirst and hunger. The dog massacre is also regarded as a premonition of the 1915 Ottoman Empire’s genocide of the Armenians. Exactly a century on, the trauma is unavoidable.

The subject appears and reappears at several points in the biennial. I came to Istanbul mostly because I had enjoyed Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s 2012 dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel so much, and wanted to see what she’d do next. Refusing the title “curator”, or even “selector” – a word, she thinks, that has sinister connotations to the Holocaust and other genocides, where selection can equal death – she describes herself instead as a drafter and researcher.

Called Saltwater, and subtitled A Theory of Thought Forms, her biennial is in many ways unfathomable. That’s fine by me. Christov-Bakargiev goes off on tangents: convolutions of waves, tides and knots, of saltwater, the circulation of the seas, the blood in our bodies, the currents in the Bosphorus, the salt in our tears, the turbulence of the world and of thought itself. There is a striving here for poetic coherence, a global positioning that in the end is impossible.

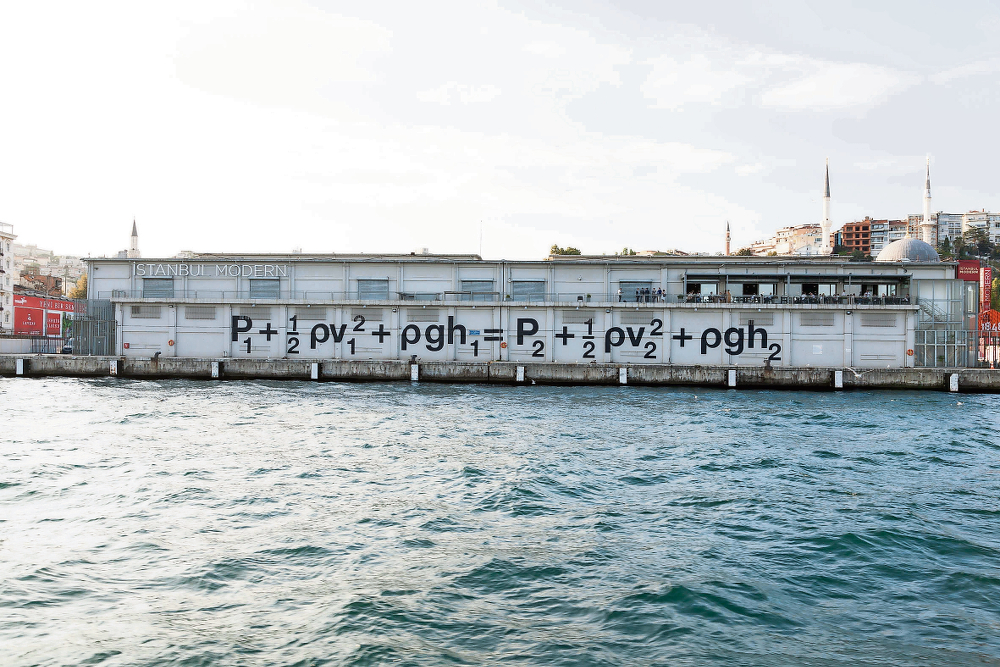

In a section of the show called The Channel at Istanbul Modern (the city’s only contemporary art museum), she connects Charles Darwin’s writings on orchids with Émile Gallé’s Art Nouveau ceramics and glassware, Karl Blossfeldt’s photographs of plant morphology, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and much besides.

Christov-Bakargiev has also, surprisingly and tellingly, installed a number of paintings by Australian Aboriginal artists at Istanbul Modern, and presents the indigenous Australian Yolngu people’s 1963 petition – typed, signed and surrounded by a painting on bark – claiming indigenous rights to their ancestral lands and to the seas. This petition eventually effected changes in Australian law. Nearby, in a four-channel video, Australian artist Vernon Ah Kee presents edited news footage of demonstrations and riots on Palm Island, Queensland, in 2004, following the death in custody of a young Aboriginal man who was detained for singing Who Let the Dogs Out? in earshot of a police car.

I find it impossible to parse this with the gorgeous drawings in cochineal by Asli Çavusoglu, many of which depict the insects that produce the colour itself, displayed in the next room, or with much else on display here.

In a shop in Beyoglu, Theaster Gates is throwing pots and playing Atlantic-label jazz albums (there’s a connection between the record deck and the potter’s wheel, the American record label and Istanbul). Nearby, in a hotel basement suite, artist and poet Heather Phillipson has set up a kind of rumpus room. Water gurgles through pipes, and the sound of sex and obsessive toothbrushing leaks through a closed door.

Hanging two biomorphic drawings by the Armenian-born abstract expressionist painter Arshile Gorky in Orhan Pamuk’s slightly ludicrous and self-indulgent Museum of Innocence in Beyoglu may be poignant, but doesn’t say much. When things come together, the biennial really works. The effect is cumulative. At its core is a striving for unity and an observance of the connectedness of past and present, the body and the world. Stories pile on stories.

In the latest of his ongoing Cabaret Crusades films, Alexandrian artist Wael Shawky tells the convoluted story of the various crusades using hand-blown Murano glass and marionettes. Shawky’s new work takes us from intrigues in Venice to the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, and Christians betraying and massacring Christians. Projected in the Küçük Mustafa Pasa Hamam, built in 1477, the building reverberates with past violence. The puppetry and caricature of the figures make the psychological effect all the greater in this great domed space.

In Francis Alÿs’s beautiful black-and-white film The Silence of Ani – set in the ruins of the medieval town on the banks of the Akhurian River that separates eastern Turkey from Armenia – children play hide-and-seek in the stones and grass, the fallen columns and walls, calling to one another in bird whistles. The town was sacked and its inhabitants massacred several times. The destruction continued into the 20th century. Armies, earthquakes and neglect have left the barest traces. The young people sleep in the grass; the birds sound in the wind. Towards the end of this elegiac film, an animated pigeon descends to strut on the stones. It is a plangent call for peace.

Christov-Bakargiev attempts a kind of synthesis here. The plight of the Armenians or of Australia’s indigenous people – not to speak of Turkey’s troubled relationship with the Kurds, or of the problems facing Azerbaijanis living in Armenia, and all the refugees fleeing Syria at Turkey’s borders – is an overwhelming flood of misery. Saltwater is no salve to despair and the ongoing tides of human misery. – © Guardian News & Media 2015

The Istanbul Biennial is at various venues until November 1