The collective hardship has similarly led to collective wellbeing strategies. Worldwide there are examples of people flocking together to share resources and promote wellbeing.

The sound of laughter echoes through the two-bedroomed house in Zola, Soweto, as groups of small children run in and out of the rooms. One boy stops at the door leading outside. A naughty smile crosses his face as he spots another child. He playfully kicks his friend on the leg, shrieks with laughter and runs away.

Four-year-old Bambanani Nkomo*, is age-appropriately playful, smiling and full of energy.

But only months earlier he seemed a totally different child, underweight and listless, with a protruding belly.

“His skin was as scaly as a crocodile, he did not talk to anyone and all he did that first day was eat,” says Smangele Radebe, who manages the daycare centre Bambanani attends each weekday.

Unlike an ordinary daycare centre, this one, run by the African Children’s Feeding Scheme, caters for 40 children between the ages of two and five who have nutritional deficiencies and provides them with balanced meals and a place to play.

Since the feeding scheme identified Bambanani as malnourished in January this year and recruited him to be part of the feeding programme, he has changed beyond recognition.

Global targets

Just weeks earlier, on the other side of the world, leaders from 192 United Nations member states met in New York to adopt global development targets aimed at making sure that, among other aims, children don’t experience hunger – something Bambanani knows all too well.

The outcome of this late-September meeting was the adoption of 17 new international goals termed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The second of these goals aims to “end all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030, making sure all people – especially children and the more vulnerable – have access to sufficient and nutritious food all year round”.

But the African Children’s Feeding Scheme’s director, Phindile Hlalele, and other experts have criticised the ambitious target, arguing that current rates of progress are too slow to achieve this goal by 2030. She says it is “an obvious impossibility”.

The SDGs follow the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – eight targets adopted in 2000 that countries agreed to try to achieve by 2015.

The first of the MDGs focused on reducing poverty and hunger by at least half of current levels and, according to the latest report compiled by Statistics South Africa, the country has largely achieved this. In 2011 only 12.9% of citizens reported experiencing hunger compared with almost 30% in 2002.

Malnutrition prevails

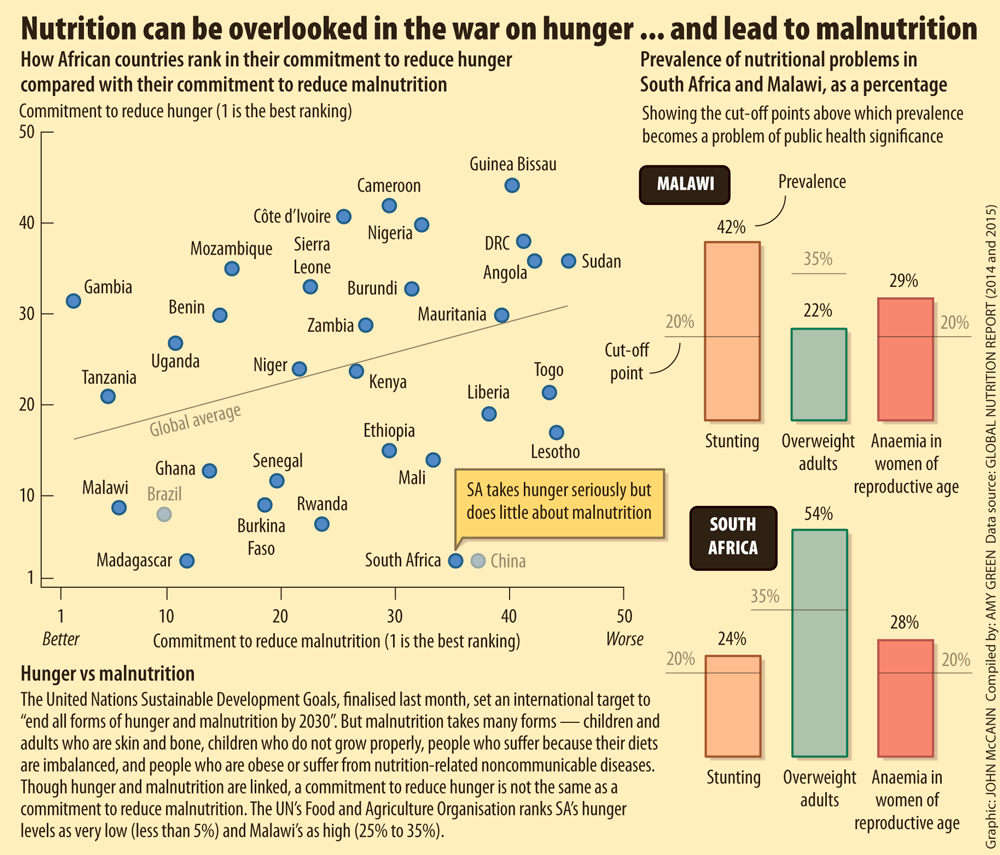

But the October edition of the Global Nutrition Report, a UN initiative, found that more than one in five South African children are stunted because of malnutrition.

Stunting, the report explains, refers to a child who is too short for his or her age. It is the failure to grow both physically and cognitively as a result of chronic or recurrent malnutrition with effects likely to last a lifetime.

According to Sheryl Hendriks of the Institute for Food, Nutrition and Wellbeing at the University of Pretoria – although South Africa performed well in many other MDG indicators – it was one of 12 countries where stunting levels increased.

“Our stunting levels are comparable to countries like Malawi where there are severe food shortages,” she says. But, unlike Malawi, South Africa has enough food to feed the population, which, Hendriks says, reveals “a far more complex problem”.

Hendriks attributes this increasing trend in under-five malnutrition-related stunting to poor healthcare, lack of diversity in diets and poor infant feeding practices such as low rates of exclusive breastfeeding, the watering down of infant foods and the early introduction of solid foods.

Emily Thomas from the Gift of the Givers Foundation, another Johannesburg-based organisation that runs feeding schemes, believes that the “magic bullet” required to make progress towards attaining SDG targets might come from a “change in mind-set”.

“We cannot reach everyone in the communities,” Thomas says. “There has to be more sustainable interventions to curb malnutrition than relying on feeding schemes. There is a need for creative measures to beat the skyrocketing food prices by, for example, adopting urban farming, which can be done in all kinds of waste containers, tyres and sacks in the spaces around people’s homes.”

Radebe agrees that feeding schemes alone cannot meet the need for healthy food in communities.

“If we are to take good care of these children, we have to be very careful with the numbers. They come in literally sick due to lack of food or poor diet,” she says.

Bambanani is proof that children can thrive with the right nutrition.

Back at the Zola nutrition centre, it’s after lunch and time for the children to take their afternoon nap. Once sick and solemn, today Bambanani is among the last of the children to take his place on the mattresses spread across the floor. He resists falling asleep for as long as he can but after about 20 minutes he can’t help closing his eyes. With his stomach full from lunch, Bambanani sleeps – together with the other slumbering girls and boys oblivious to the world around them.

In Meadowlands, in a different part of Soweto, Sonto Tsotetsi manages another African Children’s Feeding Scheme-run nutrition centre but, despite the positive impact these initiatives have on children there, she knows it is not enough.

“The children here and those part of other feeding schemes may be assured of a meal a day, but how about those that are not reached?”

One of the key messages in the recent Global Nutrition Report is that, although a great deal of progress is being made in reducing malnutrition, it’s too slow and uneven.

Even if progress was speeded up, Hendriks believes the SDG target to completely end malnutrition and hunger by 2030 to be more of an aspiration than a practically achievable goal.

“Hunger will always exist in some form or another. Poverty, food crop failures, disasters and war will always cause some degree of real hunger in pockets around the world.” – Additional reporting by Amy Green

* Name has been changed

Gloria Nakajubi, a reporter from Uganda’s New Vision, is a winner of the David Astor Trust Journalism awards and an intern at the Mail & Guardian