Sex in South Africa is in a state of emergency and has been since the colonial birth of the nation. But, since Jacob Zuma’s rape trial in 2006, when the then deputy president demonstrated his disdain for the accusation, and for women in general, a dispassionate attitude over non-consensual heterosexual sex was legitimated for a new generation.

Misogyny and homophobia are still so entrenched in a post-apartheid landscape, in spite of a progressive Constitution, that sex crimes and femicide have become an unnewsworthy norm.

Since 2004, black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) South Africans have gained more positive visibility in the media and in the arts, to an extent because of the work of the award-winning queer photo-activist Zanele Muholi, who forces the public to confront sexual prejudice by creating empowering queer art.

Astoundingly, student activism tackling heterosexual rape culture is only now getting off the ground, while the art world seems to be dragging its feet. The student movement at institutions such as Rhodes University, the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town has struck out against rape culture, using social media to “out” rapists on a “reference list” and by holding dramatic demonstrations at which students have stripped down to their underwear to make a point about “blame culture” and how we perceive women’s bodies.

In this fraught but increasingly energised context, the Stevenson Gallery in Braamfontein bravely opened an exhibition last month, titled Sex.

In preparation for this group exhibition, comprising artists ranging from Steven Cohen to Lady Skollie, the curator Lerato Bereng researched sex-related events in South Africa over the past decade, from Zuma’s rape trial to the “sex for marks” scandal in 2014 and the recent wave of student protests against rape culture.

In light of this timeline, Bereng acknowledges, “when you think of sex in South Africa, it is a dark image”. She criticises the sexual enhancement adverts posted up in the city for being “completely aimed at heterosexual sex” and describes South Africa as “a homophobic society, which offers remedies for being gay – a reality that I was very conscious of when curating the exhibition”.

The result is a show that foregrounds varying representations of same-sex desire, but fails to show the same considered approach to heterosexuality. “A lot of people have said, ‘why is the show gay?’,” Bereng admits, to which she retorts: “While there’s a lot of homosexual sex, there’s bestiality too …” and trails off.

Sex explores homosexuality through sound installation, mixed media and film. Most striking is local art duo Faka’s installation The Factory, which recreates a scene from a Johannesburg all-male sex club with a dark alcove equipped with condoms and faux leather mattresses facing a screen that plays graphic gay porn.

As an introductory piece in the show, The Factory’s shock value sets up an ironic shortcoming – the exhibition seems to come to a climax when it should just start to titillate.

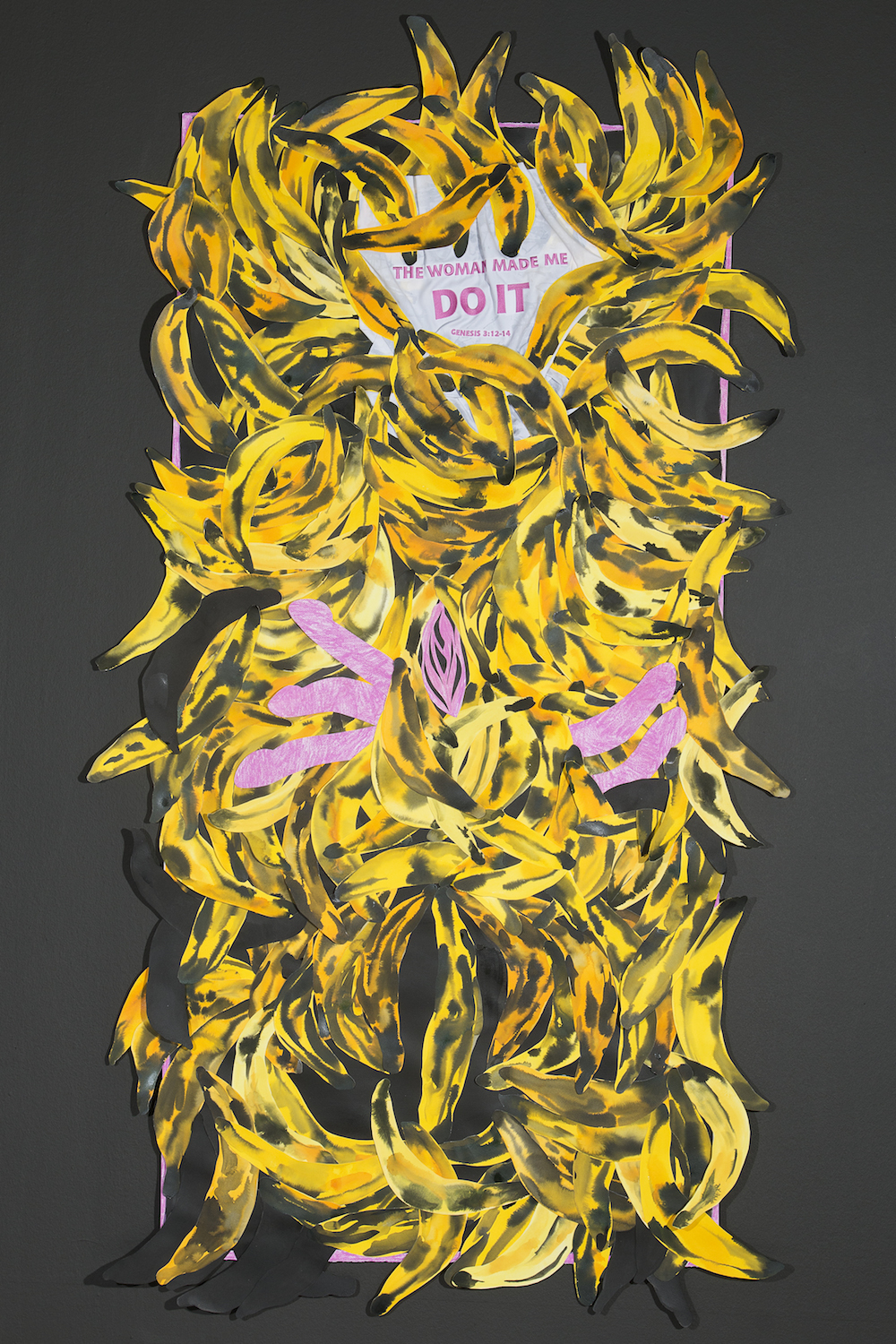

Lady Skollie’s The woman made me do it

What follows in the way of art with a heterosexual bent is a collage by Lady Skollie, titled The Woman made me Do It, which highlights the Biblical roots of contemporary blame culture used to demean and doubt rape victims.

The line from Genesis is surrounded by a sea of banana phalluses, which appear to engulf a giant vagina. The piece has a flippantly executed feel and, let’s face it, in the wake of watching hard-core anal sex, a mere suggestive symbol just isn’t going to cut it.

Although Sex shouldn’t be labelled a “gay show”, it neglects to offer the alternative forms of heterosexual sex that we so urgently need to reconfigure straight sex as a mutual, sensual experience.

Surely, a cutting-edge gallery a stone’s throw from Wits University has a duty not just to point the finger at misogyny but also to present new, liberating excavations of heterosexual acts and desires?

Notably, Muholi’s film Being Scene, which is in the gallery’s upstairs “project space”, repositions women as sexual agents. In this sensual vision of lesbian intimacy, the controlling “male gaze” is absent, countering a culture where women’s bodies are presented as objects of male temptation.

Sadly, Muholi’s film is drowned out by a centrally positioned and much larger screen, where Mapona Volume 1, stereotypical heterosexual amateur pornography, is shown.

Bereng features the film because it represents a landmark in the country’s sex timeline as the first all-black South African porn film made by black people, for black people, surprisingly as late as 2010. Although this is an interesting fact, Mapona Volume 1 conforms to over-represented hyper-heteronormative dynamics and is presented uncritically in the show without an alternative vision for heterosexual desire.

To be fair, Stevenson broaches the overall subject of sex in bold terms, but it’s failure to navigate heterosexuality through innovative representations is a real blunder. This leaves the impression that, although mutual and meaningful sex can be found in queer relationships, we can criticise patriarchal dynamics but actually having a different kind of sex isn’t an option worth exploring.

Simon Gush’s Mural