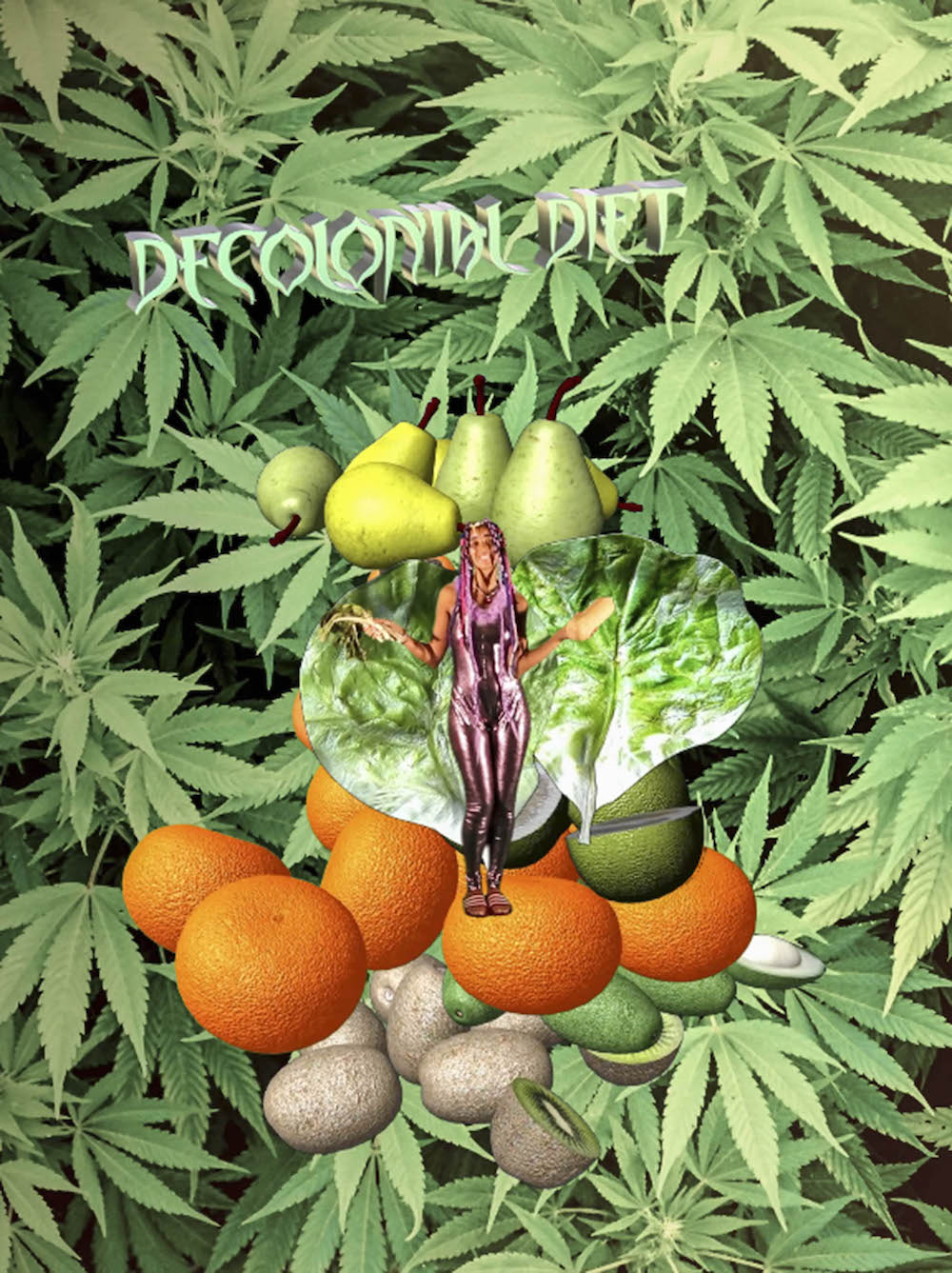

Stills of artist Tabita Rezaire’s video work which adds health

Tabita Rezaire gives warm, sincere hugs. She’s a head taller than my 1.60m and is not bothered by my pyjamas and slippers when I visit her apartment for the interview just before 8pm on a Tuesday. We live in the same building overlooking Johannesburg on the Yeoville ridge.

When I was last in her apartment in February, I was wearing a fishnet body stocking and a brown faux fur coat I had bought off the back of Jamal Nxedlana of CUSS and now Bubblegum Club fame when he used to live in this very building. It was to a party Rezaire cohosted called the “Cunty Party” – a housewarming/birthday celebration with Thato Ramaisa aka Fela Gucci, one half of performance art duo FAKA whose provocative work is currently snatching edges in edgy art scenes on the internet and in real-life Africa, America and Europe.

I didn’t get to see her kitchen that night under the pink lighting and an apartment chock-full of the queer future. Everybody in Jo’burg’s Do-It-Yourself art scene was there, dressed to honour Pussy Power as the invite had stated, and there to celebrate with the 27-year-old French-born Guyanese and Danish tech artist.

She boils the tea in a silver intergalactic vintage teapot that she bought in a charity shop. She apologises for what she thinks is a messy apartment and I put my stuff down in a baby pink fuax fur couch blanket, which I admire. “I have a baby blue one tooooo from the plaza,” she yells from the kitchen in a thick French accent. I notice a book titled Overcoming an Angry Vagina by Queen Afua next to where I have placed my keys.

When I walk into the kitchen where she is preparing a vegan dinner, I see a sonogram photograph, the ones pregnant women get from doctors. “Whose baby is this?” I ask. “There’s no babyyy, it’s a picture of my womb,” she says. I laugh, thinking it was silly of me to ask. Of course Tabita has a picture of her womb on her fridge.

She burst on to the scene as the girl who would twerk at gatherings, not only twerking as an act of sexual prowess but as a spiritual intervention that would unleash the need for those around her to twerk too. In a recorded Skype conversation between her and Argentinian tech artist and fellow twerker Fannie Sosa on Rezaire’s website, the two discuss the spiritual, healing, historical and contraceptive qualities of twerking outside the sexualised gaze of modern popular culture.

She advocates twerking and decoding the powers of the womb as health practitioner, kundalini and kemetic yoga teacher (at the Yeoville Community Centre) and someone whose work is based on physically, emotionally and spiritually empowering the self as a prerequisite to and a form of resisting the kyriarchy.

She’s a member of a marginal unit of black artists whose subject matter deals with the rigmarole that is gender, race, class, colonialism, sexuality, ableism, space, access and power from a perspective that offers personal wellness of the individual as respite, repair and revenge.

“If I didn’t have to deal with the things I’m dealing with in life, I wouldn’t make the type of working I’m doing. It’s about sharing my emotional, political and spiritual journey,” she states.

She calls herself an intersectional preacher. “Politics has failed us. Politics can only go so far and then you get stuck. All the independent and revolution talk is useless without a plan to give power for people to thrive spiritually. We need to awaken spiritually as a people.”

Visiting her website is taking a trip to a different universe where her inter-disciplinary video work and web-based art exist as an ode to decolonising the internet.

As she walks me through her collection of teas, which include nettle tea, St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum, for depression), moringa (Moringa oleifera) and 15 others in clear mason jars, we stop at the bottle of mountain mint from Mount Sinai. “How did you get tea from Mount Sinai?” I ask, and she relays the story of how she missed a flight from Cairo (where she was exhibiting and giving a talk at an electronic art festival) to Johannesburg this past May. She had never missed a flight prior to this and ended up taking the advice of a Sufi tech crew she had met at her talk and trek to Mount Sinai and Nubia instead of connect to OR Tambo.

“I went to the little cave where Moses was chilling,” she says, laughing. “After that, I took the train for 14 hours to this Nubian village on the Nile, the only place where you can drink Nile water. I saw the original pyramids of Nubia. It was breathtaking. It was such an intense feeling, that presence.

“You know you’re in front of something that carries so much energetic power. It’s a busy, touristy place but when I went inside one of the pyramids, I was the only one inside the tomb. I started to meditate and did some yoga. I was really getting into it. And then as I was stood up, the lights psheewww – out. A blackout. A minute later they came back on and I thought, ‘Oh my God, I have been acknowledged’.”

But she doesn’t romanticise the idea of ancient Egypt or Kemite. “I was continuously shifting in bewilderment about Egypt. The politics of that history and how it’s been whitewashed. The lengths people are willing to go to erase the link between the black Nubians and the pyramids.” Her face twists.

On the stove, a small pot boils quinoa and a large pan cooks a mix of spiced vegetables. “You are what you eat you know. What you put in your body really affects you on an energetic level. So not thinking about it is like not thinking about your wellness. It’s like avoiding your potential,” she says, stirring the pan.

She recently got a permaculture licence and has asked the universe for some land on which to farm.

Rezaire has identified three areas as pillars of her artistic practice: spirituality, health and technology, using each to affect the other to deal with colonial wounds. This year alone, the Central St Martins graduate (her education falls under a tab called “Brainwashing” on her website) has exhibited her video work and performance in more than 20 cities (under a tab called “Art Game” on her site) at countless global institutions of contemporary art.

After dinner, she has to pack for a trip that will see her only returning to Johannesburg (her home for the next five years) in six months. It includes a two-day hike in Switzerland with collaborator Nolan Denis before she takes up residency in Bern and thereafter exhibitions, performances, workshops and more residencies across Europe, the United States and Africa.

We move to her bedroom where we to sit on her bed while the food cooks.

A blue-haired friend of hers is in her lounge working. She talks about the difficulty of moving between one architecture of power that is the gallery system (she’s attached to the Goodman Gallery) into another one, the controlled cyberspace where her following is based.

I ask her about the relationship between the two and how cyberspace is controlled.

“That shit is dark. At least galleries don’t try to pretend they are not galleries. It’s based on exploitation but it’s very transparent. But the internet is about fake smiles and, ohhh, we are protecting people, we are changing the world and allowing so much opportunity, which is true but underlying this is a big ‘fuck you’.

“It’s a trap. They know everything about you, they make their money off of you and you give away free your labour with a smile. The fibre-optic cables that run under the ocean are placed on the same routes as the slave trade. It’s not colonial empires anymore but media empires. Have you ever read the terms and conditions agreement? Never. We are so blind and so trusting that we don’t care about our security, our mental health, surveillance. And we are addicts.”

Although she is hyperconscious about it, she acknowledges that the internet also has its benefits. “It’s about how you can use them for your own benefits, how you can use social media to serve others. Ifweuseitasatooltoexpandour consciousness instead of making it an ego thing or self-promotion, it’s good,” she says.

Denis, Rezaire and fellow tech healer artist Bogosi Sekhukhuni are part of NTU, “an agency concerned with the spiritual futures of the internet, which provides decolonial therapies for the digital age”.

So what exactly does that mean? I ask.

She leaves the room to get the packaging for NTU’s seed packs. She hands me a large silver packet with a sticker of the sacred Khoi and San bulb Boophone disticha, a plant the Xhosa call incwadi – it’s poisonous and one ingests it in small doses to transport users to states of higher consciousness.

NTU will be “selling” indigenous seeds and plants on a website they are launching at the Berlin Biennale this week. To access the crypto currency NTU has created to trade the healing products, users will have to upload emotional data about their experiences around oppressive systems by filling in a form on the site.

“I’m also working on a performance in which I reclaim the word hotep [which is colloquially used to describe a particular kind of black male patriach], which I spell HOEtep.”

She’s anxious about the next few months and not being grounded. As the night thickens, I see that her mind has moved to the complex task of packing for a six-month journey that begins in a few hours, which she hasn’t started. I tell her I’m going to visit Credo Mutwa on Saturday and she breaks into a song of “oh my gods”.

“That’s huuuuge. You are not being for real. It’s my dreaaaaaam.” She buries her head on her lap and keeps quiet. Her face emerges again and she asks: “Is it open to the public? Oh my god. I feel like I should postpone my flight.”