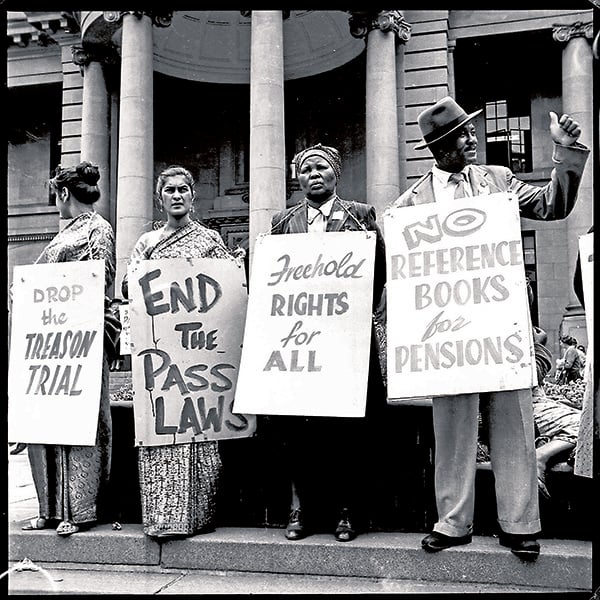

The crowd at the Union Buildings on August 9 1956. About 20 000 women marched to Pretoria to protest against passes for black women.

To celebrate the 60th anniversary of the anti-pass march to the Union Buildings, we profile 60 of its participants and organisers.

1. Albertina Sisulu

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)

One of the most revered figures to emerge from the historic Women’s March and the anti-apartheid struggle was Albertina Sisulu, renowned champion of freedom. Born in the Transkei in 1918, Albertina Thithewe was the eldest of eight girls. She trained as a nurse, later moving to Johannesburg. She married activist Walter Sisulu in 1944 and joined the ANC Women’s League in 1948. In later years, she said: “I joined ANC in 1948 because of Lilian Ngoyi … The way she used to preach to me about the future of the child you are going to bring into this world.”

She rose to a leadership position both in the ANC and the Federation of South African Women in the 1950s, as well as qualifying as a midwife during this time. With a strong desire to promote education, she opposed inferior “Bantu” education and used her home in Orlando West as a classroom for alternative education for some time. Albertina was one of the organisers of the anti-pass Women’s March in 1956, playing a key role in planning the logistics involved in helping women bypass police blocks that were barring large groups from travelling to Pretoria.

She said later: “The 9th of August was an eye-opener, in the sense that we thought that men could really be the people to carry reference books. But when it turned to us, we felt it’s something else now.

“We had four women and four deputies in case one is not well or she does not come. We had Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph, Rahima Moosa and Sophie Williams. And we named those deputies. Lilian had Bertha Gxowa, and Rahima had Amina Cachalia and Helen Joseph had Violet Weinberg.

“We all stood and sang Nkosi Sikelele. You can imagine 20 000 voices in that amphitheatre, ungathi iya shukuma [it was like the amphitheatre was shaking].”

Arrested under the General Laws Amendment Act in 1963, she was kept in solitary confinement for nearly two months. Sisulu was again detained and put in solitary confinement in 1981 and in 1985, as well as being served with banning orders and put under house arrest. When the ANC was unbanned in 1990, she helped re-establish the ANC Women’s League. After the 1994 transition to democracy, both Albertina and Walter became members of parliament.

Albertina eventually became known as the “mother of the nation” for the grace and strength with which she dedicated her life to the struggle for human rights. — Tracy Burrows

2. Amina Cachalia

Amina Cachalia, second from left. (Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)

One of 11 children, Amina Cachalia was born in 1930 in Vereeniging. She described herself as born into the struggle; her father Ebrahim Ismail Asvat was a leading political activist who joined Mahatma Gandhi in the Passive Resistance Campaign in 1906.

A determined campaigner from her teenage years as a member of the Transvaal Indian Youth Congress, the 18-year-old Cachalia worked in establishing the Women’s Progressive Union in 1948, which aimed to assist women in becoming financially independent.

She met and married Yusuf Cachalia, also an activist and political leader. He was secretary of the South African Indian Congress, and directed the Defiance Campaign of 1952 with Walter Sisulu. Amina joined as a volunteer and was arrested for the first time.

In 1954, she united with other women leaders in forming the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw), where she served as its first treasurer. The preparation for the 1956 Women’s March was an incredibly stressful period, as Fedsaw had no funds, so it was up to local women to raise transport funds for the march through cake sales and other activities. Cachalia oversaw the women of Fordsburg, Newlands and Langlaagte.

Cachalia worked tirelessly to convince fellow Indian women in her community to take the risk and join the protest. This was a real challenge, as many lived in strictly traditional households, and needed their husbands’ permission to attend.

On the day of the March, it all paid off. Women came out in unprecedented numbers: 20 000 from all over the country, showing their willingness to stand up and contest the oppression of the pass laws for women.

Cachalia was six months pregnant as she stood on the steps of the Union Buildings and addressed the protesters, joining Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Sophie Williams-De Bruyn in carrying the thousands of petitions to the door of Prime Minister Strijdom’s office.

In 1963, after travelling throughout the country visiting political activists who were relocated from urban to rural areas, she was banned by the apartheid state. Her banning and house arrest lasted 15 years.

Despite this, Cachalia was involved in fighting against the Indian and Coloured Council representatives, and in forming the United Democratic Front. After liberation, she was chosen to be an MP in the country’s first democratic elections in 1994.

In an interview with Sibahle Malinga on the Women’s March, published in 2006, Cachalia said: “People need to be more informed of the important events that shaped and altered our country’s political landscape.” She also noted the serious absence of powerful and organised women’s structures in South Africa today.

In 2004, Cachalia received the Order of Luthuli in Bronze for her lifetime of work. Her autobiography, When Hope and History Rhyme, was released shortly after her death in 2013. — Romi Reinecke

3. Annie Peters

Anne Peters, affectionately known as “Ouma Annie”, was born in Heidedal in 1920 near Bloemfontein, and was schooled there and in Lesotho. As a young schoolgirl Peters became politically aware as a result of protests against the Bantu education system. When she was 16, she left school and moved with her mother to Sophiatown. Her mother, who came from a marriage between a Scotsman and the daughter of a Basothu chief, was classified coloured but because she could pass for white, was allowed to travel in the whites-only section of the trams, while Peters had to sit in the area restricted to blacks.

While working in Sophiatown as a tap-dancer, Peters was one of many who stood in defiance of apartheid legislation, particularly the dompas or passbook.

“I refused to get a passbook. I was also a human being, even though I was black,” said Peters.

She was one of the 20 000 women who took part in the Anti-Pass March to the Union Buildings in 1956.

“When we got to the Union Buildings … we all tore up our passbooks. The place was dirty with the dompasses. It was called the dompas because it was ‘dom’; it was silly. We didn’t care what the police would do to us.”

The years that followed saw forced evictions in Sophiatown, and Peters was moved to Meadowlands. A few years later she moved back to Bloemfontein, where she worked at Oranje Mental Hospital. Throughout her life, she fought to ensure racial freedom for all. Peters died in 2007. — Linda Doke

4. Annie Silinga

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)

Annie Silinga was born in 1910 at Nqqamakwe in the Butterworth district of the Transkei, where she completed just a few years of primary school. In 1937 she moved to Cape Town, where her husband was employed.

Aged 38, she joined the Langa Vigilance Association, and in 1952 the ANC. During the Defiance Campaign of 1952, she was jailed for a short time for civil disobedience.

Silinga was elected to the executive committee of the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw) in its founding year, 1954. Despite being almost illiterate, her determination and passion saw her become one of the leaders of the women’s anti-pass campaign. As one of the founder members, Annie attended Fedsaw’s inaugural conference, where the Women’s Charter was written.

At a Fedsaw meeting on the Cape Town Parade, Annie declared: “I will never carry a pass, I will only carry one similar to Mrs (Susan) Strijdom’s. She is a women and I am too. There is no difference.”

In 1955 Silinga was arrested for refusing to comply with pass regulations, and after several appeals was banished and sent under police escort to the Transkei. She returned illegally to be with her children and husband in Langa. In 1957 she finally managed to successfully appeal her case, on the grounds that having lived in Cape Town for 15 years she had the right to remain there.

During 1956 Silinga was arrested for treason, sent to Johannnesburg and detained with other leading women activists such as Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Francis Baard. The Treason Trial lasted for four-and-a-half years.

Upon her release, Annie was elected president of the Cape Town ANC Women’s League, and was jailed in 1960 during the state of emergency. She was involved in the formation of the Women’s Front, and was made a patron of the United Democratic Front in 1983. She died a year later, having never carried a pass. — Linda Doke

5. Ayesha Bibi Dawood

Ayesha Bibi Dawood, nicknamed Asa, was born in in 1937 in Worcester to an Indian merchant and a Malay mother.

Her awareness of the apartheid laws, particularly the Group Areas Act and the pass laws, began as a young girl, while reading the newspaper to her father. In 1951 she volunteered to help organise a one-day strike against the pass laws.

Soon after the successful strike, she was elected secretary to the chairman of the Worcester United Action Committee. Dawood worked closely with the ANC, calling for volunteers to defy apartheid laws. She diligently sought to unionise workers from industries outside of the food sector, and numbers grew. By 1952, Worcester led the Western Cape in activism, with more than 800 “defy-ers” signing up. Dawood’s home was the centre of the campaign.

In 1956 Dawood and some of her fellow members were charged with incitement and detained for nine months under the Suppression of Communism Act. She was arrested in the same year and charged with high treason, along with 155 others. She was forced to leave the country in 1968 and only returned after South Africa became a democracy. She now lives once more in Worcester. — Linda Doke

6. Bertha Gxowa

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)

Bertha Gxowa was born in 1934 in Germiston location, where she attended Thokoza Primary and Secondary schools. Her father was a garment worker and the first black man to work on the cutting floor, previously reserved for white labourers only.

Permits were required to live and move around Germiston location, which triggered her interest in opposition politics. She volunteered to be in one of the first groups of defence campaigners who went into Krugersdorp without permits. She was arrested for this and spent 10 days in prison after refusing to pay the fine.

Gxowa started her working life as an office assistant for the South Africa Clothing Workers’ Union, and studied bookkeeping and shorthand at a commercial college.

Signing up to the ANC Youth League during the anti-Bantu education campaign strengthened her involvement in politics, but her focus was more on women’s issues. She became a founder member of the Federation of South African Women, and travelled South Africa with Helen Joseph, collecting 20 000 anti-pass law petitions that were to be delivered to the Union Buildings during the historic women’s march in 1956. Between 1956 and 1958, Gxowa was a defendant in the Treason Trial, and in 1960 she was banned for 11 years under the Suppression of Communism Act.

Bertha died in 2010 aged 76. She was posthumously awarded The Order Of Luthuli in Silver for her great contribution to trade unions, women’s movements and the struggle against apartheid. — Linda Doke

7. Bettie du Toit

Born in the Transvaal in 1902, Bettie du Toit was a trade unionist of note. Her mother died when she was just 18 months old, and she was orphaned at three when her father passed away. This meant that she grew up at a boarding school run by the Dutch Reformed Church in the Platteland.

She moved to Johannesburg at 18, where she met prominent trade unionist Johanna Cornelius, under whose guidance she became involved in trade unionism and political activism. Du Toit worked with various trade unions such as the Pretoria Match Workers’ Union, the Textile Workers Industrial Union, the Transvaal and Natal Canning Workers and the National Laundry, Cleaning and Dyeing Workers Union.

Du Toit also played a significant role in political activism. She protested the Asiatic Land Tenure Act (also known as the Ghetto Act) and was one of the volunteers in the Defiance Campaign. Her involvement in the campaign led to her being banned in 1952, under the Suppression of Communism Act.

As a result of the banning, she was prohibited from taking part in any trade union activities for the rest of her life. However, in spite of being banned, she helped initiate a welfare organisation called Kupugani in Soweto, and would travel to the township at night in disguise, until this was discovered by the police.

After being arrested several times, she left South Africa and went into exile in Ghana in 1963, eventually moving to London. Later in life, Du Toit developed Stevens-Johnson syndrome after suffering an ear infection, and lost her sight. This inspired her to teach Braille to other visually-impaired individuals. She returned to South Africa post-apartheid and passed away in 2002. – Fatima Asmal

8. Caroline Motsoaledi

Born in Middelburg in 1927, Caroline Motsoaledi grew up on her grandfather’s farm. She left school in standard six and moved to Johannesburg, where she became a domestic worker, joined the ANC and met her husband, the late Elias Motsoaledi, as well as activist Lilian Ngoyi.

Motsoaledi played an active role in the establishment of the Federation of Transvaal Women (Fedtraw) in 1954 and was active in planning the 1956 Women’s March, going from house to house to encourage people to sign the petition. She told interviewers: “I was carrying my five-month-old son on my back that day. When we got off the train in Pretoria we walked to the Union Buildings, I was shocked at how much participation there was, as while campaigning we were worried there wouldn’t be a huge turnout from the provinces.”

She became the treasurer of Fedtraw’s Soweto Branch in 1984 and was active as a shop steward at Dumas Clothing factory. She was also instrumental in the formation of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985.

Speaking at her funeral in Soweto in 2015, Minister of Water Affairs Nomvula Mokonyane described the late ANC activist as a “strong woman and a true revolutionary”. Gauteng Premier David Makhura described “Mama” Motsoaledi as a “beloved mother, a pillar of strength to her family, an accomplished freedom fighter in her own right, a defender of the rights of women and the rights of workers as well as an educator to many in her community”.

President Jacob Zuma said in a letter of condolence: “She endured detention without trial, remained steadfast in support of the struggle inside of all the harassment the regime inflicted on her, and continued against all odds to hold the family together in their commitment to the struggle.” — Tracy Burrows

9. Cecilia Rosier

Cecilia Rosier (née Kodesh) was born in Benoni in 1918 and moved to Cape Town at the age of six. During the Great Depression her father lost his business, and her mother opened a grocery store in Gimpie Street, Woodstock — a street notorious for drugs, prostitution and gangsters. The family lived in two rooms at the back of the store.

They eventually moved out of Woodstock but according to Rosier’s twin brother Wolfie, living there led to his and his sister’s politicisation as children, because they recognised that it was not right for people of colour to live under circumstances which they — as whites — could more easily escape.

As an adult Rosier joined the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and married Hymie Rosier, the treasurer of its Cape Town branch. Rosier worked as secretary to the CPSA’s general secretary Moses Kotane for several years.

She was one of the founding members of the Federation of South African Women and was elected its treasurer in 1955. She was detained and held for three months under the state of emergency in 1960, and then withdrew from political activity to concentrate on her family. She remained in Cape Town until her death in the early 1990s. — Fatima Asmal

10. Chrissie Jasson

Christina “Chrissie” Jasson was born in 1928 and worked as a clerk. She was active in the Port Elizabeth trade union movements, organising food and canning as well as textile workers, and leading several strikes. She was acting secretary of the Eastern Cape Action Committee from 1954 to 1955.

Jasson participated in the 1955 founding conference of the South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu) as a delegate of the Textile Workers Industrial Union and was elected to its national executive committee.

When the founding conference of the Federation of South African Women was held in the Trades Hall, Johannesburg, on April 17 1954, a national executive committee was elected, with Jasson as part of it.

Jasson was later one of the accused in the Treason Trial. When she was arrested she was pregnant, and her child was born during the trial. The charges against her were eventually withdrawn. She died in 1999. — Fatima Asmal

NEXT: 11-20