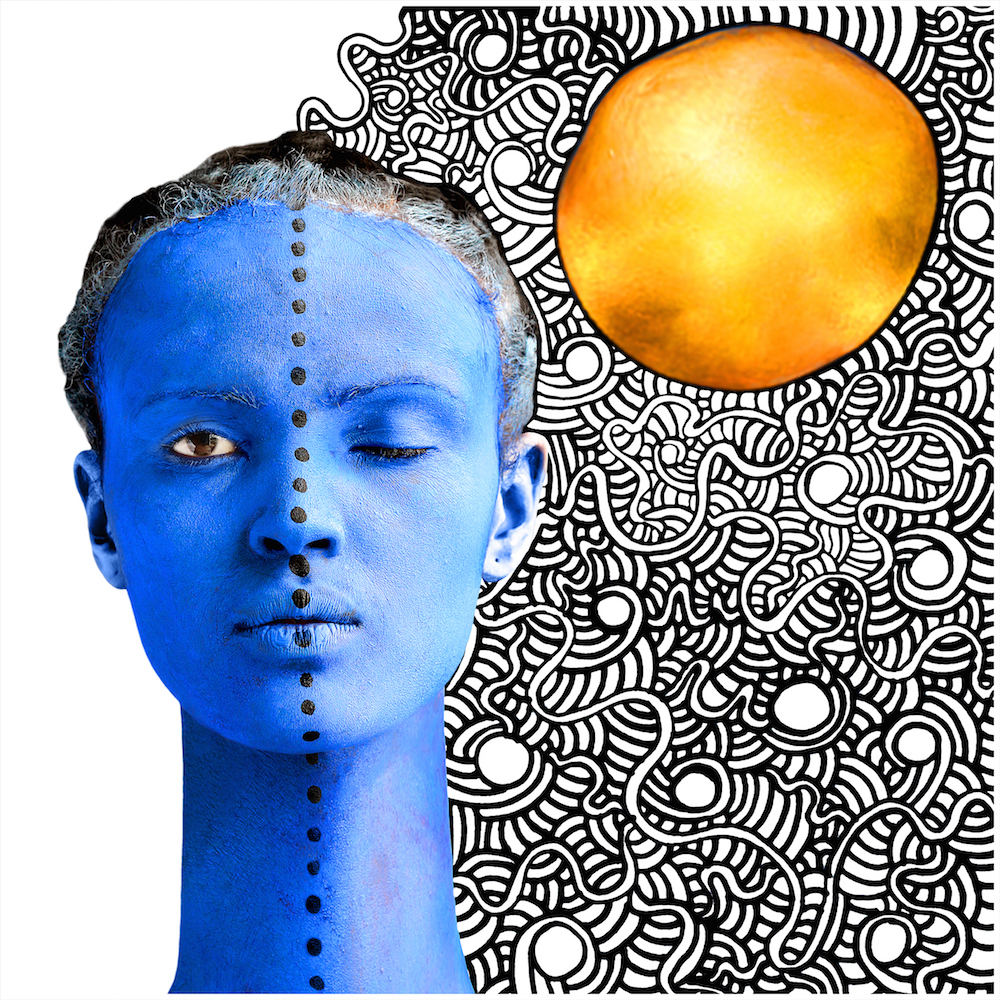

Fantastic display: Phyllis: I am Not Alone by Zina Saro-Wiwa

Around the time of the collapse of TB Joshua’s hostel in Lagos, an event in which a supposed life restorer cheaply turned the death of more than 80 people into a conspiracy, I mulled over a phrase uttered to me by Asonzeh Ukah.

Ukah, a University of Cape Town-based historian of religion, surmised that even though Joshua could not heal the Ebola-stricken in Liberia, the man was unmistakably a manufacturer of miracles — “miracles as commodity”.

Ukah’s turn of phrase again visited me as I took in the stridency of Andrew Esiebo’s photographs at the Fantastic exhibition.

Fantastic, showing at the Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg, draws on literary references to carve “a language of subversion that de-legitimises historical narratives that flatten the depth of the lived experience”, as curators Nkule Mabaso and Nomusa Makhubu write in their statement.

The show collates the previously exhibited work of Esiebo, Aida Muluneh, Jelili Atiku, Dineo Bopape, Kudzanai Chiurai, Milumbe Haimbe, Terence Nance, Tracey Rose, Zina Saro-Wiwa and Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum into a show with a forceful grasp of its curatorial premise.

The exhibition draws primarily on photographs and video, although there are mixed-media works and a graphic novel.

In one of the photographs, Esiebo depicts a Mountain of Fire and Miracles Ministries scene in which a mass of worshippers are in various stages of prostration, either in voluntary supplication or having been felled by the hand of an omnipotent man of God. Who will know? Esiebo’s sense of spectacle and his framing posit him both as a dispassionate observer and a fervent objector.

His photographs, three of which are featured in Fantastic, are entitled God Is Alive, yet the pictures depict something akin to a valley of death.

Rose’s Maqueii seems to speak to the “omnipresent mystery” of government — a dose of government magic, as it were. Rose’s supernatural, jester-like figure — whiteface to match her Victorian frock — balances mockingly on a roadside aluminium railing. This is digitally doctored to form a 90˚ cordon that unfurls into a blurry RDP landscape behind it. She seems to offer South Africa’s landless masses a three-course meal of roads, RDP houses and desolate wastelands.

She holds two props in her hand: a candy cane fitted with an absurdist mask and a chocolate cake ready to be served contemptuously.

Utterly commanding is Atiku’s Eleniyan, an enduring video of a performance enacted in February 2012 at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. Atiku’s performances have increasingly come under sharp focus in Nigeria, particularly in his home suburb of Ejigbo, in Lagos State.

In Eleniyan, he seemingly pillages Makerere’s sculpture department, coming into view as he carries skeletons across his arms, on his back and a lone skull dangling from his groin.

As this performance forms part of his In the Red series, Atiku is clad in his strappy, full-body red cloth ensemble that renders him as a human-sized crustacean.

For Atiku, red is the colour of “life, violence and energy — the essence of human life”. That he places his skeletons on a sheet of red, at the centre of the campus’s driveway, is self-explanatory, but Atiku’s performance is abortive in an epiphanic way.

Having suspended two skeletons from a tree, he performs something resembling a self-strangulation when he seemingly tries to pull himself up to join them. Atiku’s anguished growls can be read as the frustration of being unable to complete this calvarian crucifixion.

Saro-Wiwa’s work, represented by a trilogy of photographs (Phyllis: I Am Not Alone, Phyllis Phyllis and Phyllis Street Hawker) and a video entitled The Deliverance of Comfort, strikes a tone that is less grave, deriving its currency from the layering of symbols that hold contested meaning.

There is something quite evocative in that Comfort, the trickster “child-witch” who must be exorcised, is a girl child, restrained and sanitised by four male zealots. Comfort inhabits a post-colonial cultural milieu so tinctured with reconstituted myths that her exorcism is an Armageddon of mythologies.

Fantastic, from Chuirai’s Creation to Haimbe’s Ananuya — The Revolutionist, highlights the role of women as keepers of counterhegemonic secrets. By gathering these and other works into a cohesive whole, the curators force us to consider “contemporary complexity” in fulfilling ways.

Although the exhibition would breathe better had it been given the showroom space it deserves, Mabaso and Makhubu insist that the limits of space force interesting parallels, allowing the schematic and thematic vision to stand out.

The themes of religion and gender in relation to global capital seem more prominent in this particular iteration, says Makhubu.

Saro-Wiwa’s The Deliverance of Comfort next to Esiebo’s God Is Alive. Saro-Wiwa’s wig-peddling Phyllis sitting close to Rose’s Marie Antoinette lampoon and Haimbe’s critique of the woman-erasing corporation seem to swivel right back to 15th-century European art and to more recent African witch hunts.

Whether cornered and relegated to elevator music, Fantastic is confrontational, forcing the viewer to take note.

Fantastic runs until December 15.