The work Bopape will be installing at Art in General in Brooklyn

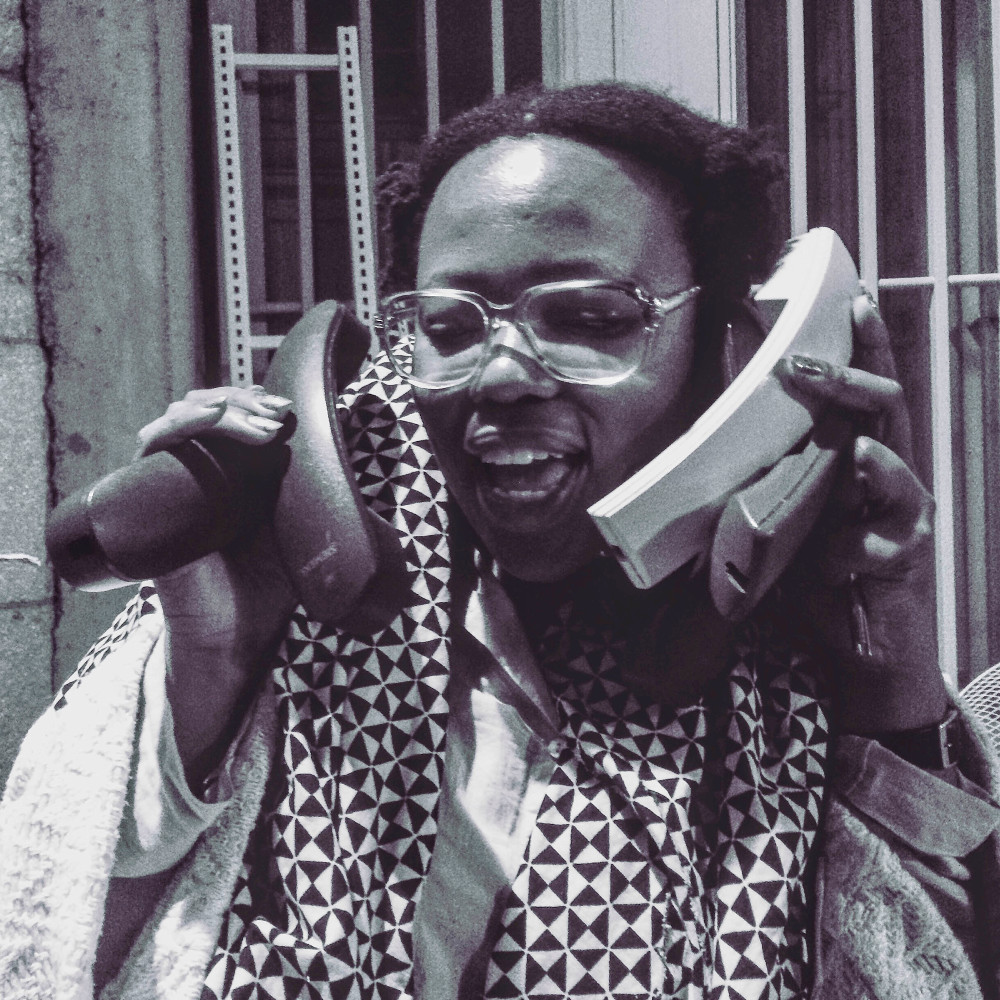

Consider Dineo Seshee Bopape. Right now she is a voice. Disembodied. Streaming out from the screen. A blinking machine. The voice is rough with exhaustion. Gravelly at the bottom. Slow and languid at its core. She is a voice, somewhere there, and a screen with far too many tabs open, in need of rest somewhere there on the other side of the world.

It’s 7am in New York and the artist is up early for our video call. She’s there for her first solo show in the United States, and what kind of fates would have planned this timing? The United States are not so United.

Donald Trump of entrepreneurial, orange-faced racism is in the running for a seat as the nation’s most important citizen. His opposition candidate, Hillary Clinton, is a self-proclaimed intersectional feminist with a history of buried rape scandals and a white husband who was deemed “the first black president of the US”. And the videos of the police killings that keep coming. Shot lo-fi on cellphones, sometimes there is a scream off camera. Or some other nondiegetic sound indicating the presence of another character. Something other than the black body, the bullets, the men in blue, the blood. Now here on your screen, playing within the safety and comfort of your home, your office, your car.

But back to this screen, to this sound and this voice. The work Bopape will be installing at Art in General in Brooklyn, New York, is a continuation of the work shown at the 32nd Saõ Paulo Biennale earlier this year.

“Well,” she elaborates. “It’s a continuation of all the work I do, I guess. I’m thinking about holes. About holes in memory. About how mirrors can provide holes, how they can perforate the illusion, break the linearity. A mirror can offer something different, a different perspective. An opportunity to go to the other side.”

The show, :indeed it may very well be the _____ itself, is centred on a set of dense, dark rectangular and round blocks of what looks to be soil or clay. In the blocks are holes, cavities and mounds of varying shapes and sizes. Some of the holes are implied: circles outlined in coloured chalk. In the cavities are gold leaves, herbs, petals, stones, tiny fist-shaped sculptures, gemstones, coal and little glass bottles filled with unnamed materials. On some of the blocks are chalk drawings that resemble Adinkra symbols.

“I’ll be working with soil and clay, and hopefully feathers.”

Bopape has not yet managed to locate the feathers she seeks. The quetzal with its brightly coloured plumage is found in Central American mountainous rainforests. There is folklore about the bird: the quetzal commits suicide in captivity.

This is but one myth mentioned by Bopape during the course of our conversation. In another, Marie-Joseph Angélique, a Montreal slave, razes the city to the ground while trying to escape with her lover.

“I’m interested in that moment of passion that sets everything around it alight. That saturation of pain, of no longer being willing to endure it. That is rebellion. I think of Khwezi, Fezeka. Of that rebellion spirit of standing up for herself. That moment when a ‘no’ reverberates. When you refuse to comply. When you refuse to go with the order.”

Madness among the rebels

Frantz Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth: “In the period of colonisation when it is not contested by armed resistance, when the sum total of harmful nervous stimuli overstep a certain threshold, the defensive attitudes of the natives give way and they then find themselves crowding the mental hospitals. There is thus during this calm period of successful colonisation, a regular and important mental pathology which is the direct product of oppression.”

Consider Bopape. Consider Insanity. Holes in the mind, in the memory. Psychic dissolution. Consider, perhaps, madness as a form of freedom.

Her 2016 show, Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings], saw the walls of a room in Palais de Tokyo in Paris wrapped in an orange-ish, reddish colour. In a corner, buckets placed at different levels (some on the ground, some elevated on plinths) slowly fill up with water dripping from the ceiling, one drop, drop, drop at a time.

“The buckets had a contact mic underneath that picked up the sounds of the drips and amplified them. And the sound was manipulated to make it deeper. We gave them bass so they sounded like a drum. And the drips were going at different rates, one was at three seconds, one was at 2.5 seconds and one was every minute.”

The vessels accumulate liquid mass at an excruciating pace. Gradual, unhurried, but definite. One thinks of Chinese water torture. Of drops of water dripping on to the forehead, resulting eventually in a break of the conscious. In insanity.

“The dripping then was also drumming. Drumming as a call to action. As summoning. There’s a Macy Gray song I like called Oblivion and that song spins you around and spits you out. And that’s what I wanted with the drips, or drum beats at different rhythms. When you lose your mind, it can be a gift. You can be detached. You can be free. You can be loose.

“In the Macy Gray song, the walls collapse and the madness gives one possibility. I’m thinking about the buckets filling up, slowly, drip by drip, and eventually overflowing, spilling out and filling the whole space. And then the walls crack and suddenly it’s open. Suddenly, there’s light and possibility.”

“I’ve been thinking a lot of mental instability, which is an ongoing theme in my work. I’ve been looking at Fanon’s writings on the causes of madness. Madness as the result of socioeconomic and political factors.”

This madness. WEB du Bois’s double consciousness. Tsitsi Dangarembga’s nervous condition. Ralph Ellison’s invisibility. Bessie Head’s question of power.

What does it mean to lose your mind? To take leave of your senses? To be so full of life, so full with it, that its spills out from inside you and drowns you, submerges you? What does it mean for a people (whose reality has been dispossession, violence and oppression) to break from reality? Is it an act of rebellion? A righteous riot? Is it a step towards a freedom that only has room for one, and even then only sometimes? It is perhaps taking things to their logical conclusion; a rational response to an unreasonable world. Or is it what it always has been, madness this time like the madness before it?

“Even in the South African context,” she adds. “When it comes to our history… and how it has been written. How does one grapple with it? How does one attempt to be sane?” In this country, the pop version of our history, the palatable one begins and ends in forgiveness.

“But what does that mean?” asks Bopape. I am unable to answer. I struggle with the term and its trappings. I’m not sure I know what it’s supposed to feel like.

“What does it mean to forgive politically and what does it mean to forgive personally? My father has Alzheimer’s so he forgets. And I have to forgive. To forgive him for forgetting. Forgive him for forgetting me. But what does it mean? Is it just wanting things to continue? What about recognition? What about adjustment? Chis Hani’s wife [Limpho Hani] comes to mind in her refusal to forgive, her refusal to just comply. Because fine, time has moved on, but what does it mean to still be in this body? To be the one left with the memory? What does it mean to remember?”

Her 2013 work, but that’s not the important part of the story, is an installed sculpture of mirrors. “…big mirrors, small mirrors, car mirrors, pocket mirrors. I had built a sculpture before and burnt it. The burning was recorded, and a video of the recording was installed in a new structure built similar to the burnt one.

“So it contains the memory of the other structure, of the burning. And this is reflected on to the mirrors, which reflect it on to another mirror, but maybe losing something each time. Maybe not losing, but omitting. It seems continuous but each time you move, it breaks your position of encountering the story. You’re given one particular angle, but as soon as you move, it collapses.”

Is this collapse in the singular, this break? Is this where the madness seeps in?

How does something new come into the world?

Through fire, water. Through ash.

“Sun Ra spoke a lot about the place and position of blackness. About what is means to exist as a shadow. To exist as nothing. I read somewhere that during one of his shows, he went around the audience screaming at them ‘Now give me your death!’ and I thought it was crazy. To demand this from people. To demand their lives.

“It was madness, but this beautiful delirium in which he advocates killing yourself. Killing yourself as in breaking down the thing that holds you back. When you’re no longer the thing that people say you are, you’ve successfully killed yourself. That you no longer exists, but now you are free. So what do you have when all you have is nothing? Nothing can be beautiful. It can be liberation.”

Dineo Seshee Bopape is the Standard Bank Young Artist of the Year for Performance Art, 2016. She co-owns NGO — Nothing Gets Organised, an experimental project space founded by Johannesburg based visual practitioners and artists Dineo Seshee Bopape, Gabi Ngcobo and Sinethemba Thwalo. Located in the Johannesburg CBD, NGO is interested in un/conventional processes of self-organising — those that do not imply structure, tangibility, context or form. It is a space for (NON)SENSE where (NON)SENSE can profoundly gesticulate towards, dislodge, embrace, disavow, or exist as nothingness! Research is ongoing, malleable and open ended. NGO pursues that which becomes publicly visible as always already processes in motion — to which we confer context, name and identity.