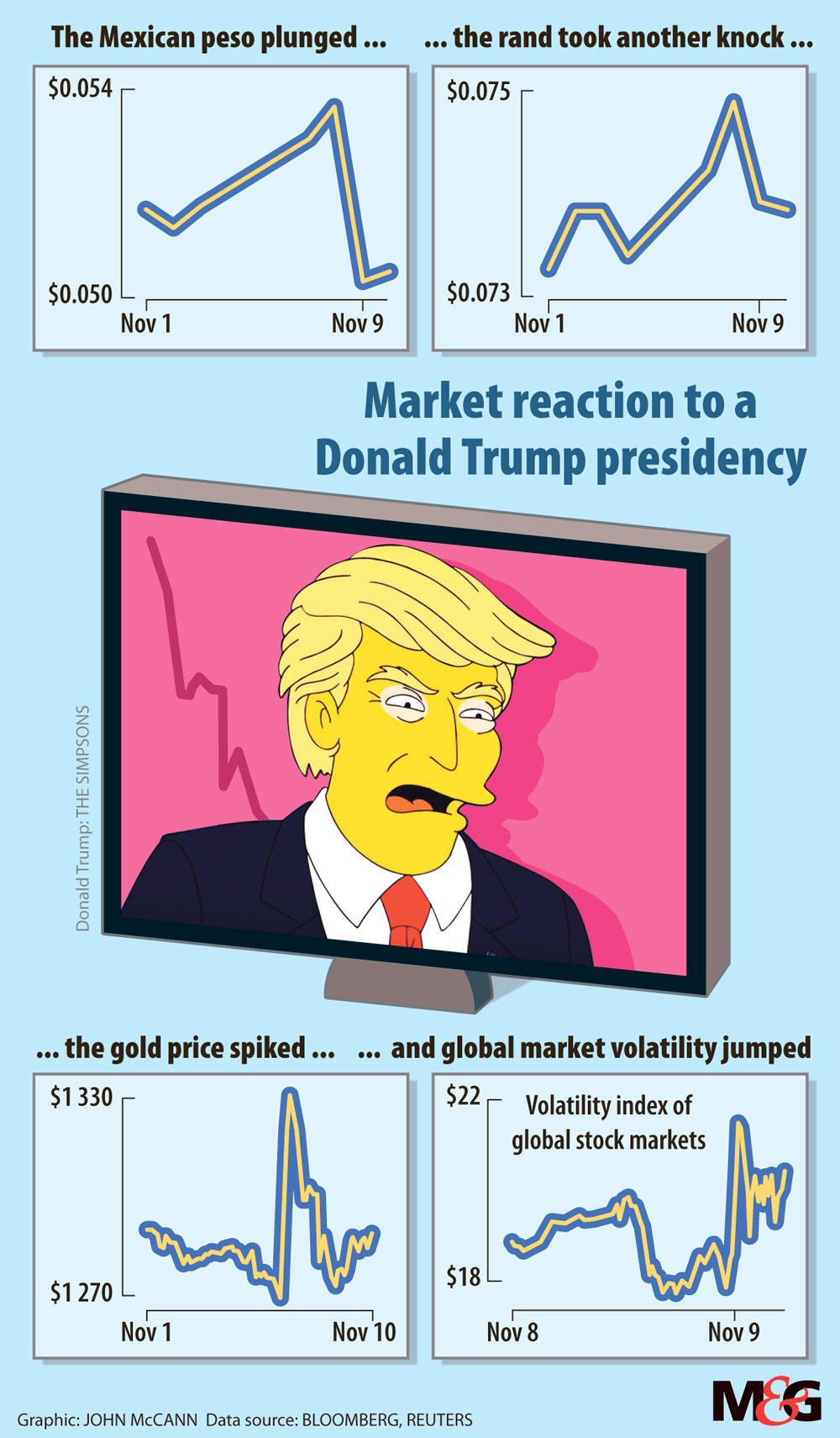

It’s the morning after and the world remains in a state of disbelief: Donald J Trump has been elected president of the United States. Parts of the markets were lifted by the news, other parts dipped, but mostly they appeared paralysed by the quintessential WTF moment.

Money rushed into safe havens such as gold, and resource shares were also lifted. The dollar weakened, as did emerging market currencies. At first the rand lost 50c to the dollar and the JSE shilly-shallied as it tried to come to terms with the implications but ultimately closed higher, supported by a rally in mining stocks.

In the United States, exchanges boomed as healthcare, banks and private prison stocks surged and the Dow Jones industrial average closed at a record high.

“The reaction so far has been surprisingly limited especially compared with the post-Brexit reactions,” said Peter Attard Montalto, the emerging markets analyst of Nomura.

In a note by City Index’s Kathleen Brooks, she said it was likely that traders “have no idea how to price in his victory as we have no precedent for someone like Trump”.

Although he is likely to have the support of a Republican-dominated Congress, it does not mean that his political party fully supports his policy approach. “He is going to have to work hard to unify his party, and will have to accept some compromises in getting his policies approved,” said Kevin Lings, the chief economist of Stanlib.

Trump had an advantage because of a weak opponent, Hillary Clinton, who trounced Bernie Sanders — who arguably had a better grip on growing inequality in the US — as the Democratic candidate. Presumably disenchanted with their options, only 50% of the electorate voted.

But it is likely that Trump’s strident promise of change clinched the deal, and it seems that he will deliver on that. But whether it will be for better or worse has yet to be seen.

“Trump’s victory … is likely to bring a set of policies that diverge sharply from those of the prior administration,” said Robard Williams, a senior vice-president of the US-based credit ratings agency Moody’s.

It identified five key areas where the new administration’s policies will most likely have an effect: international trade, financial regulation, healthcare, immigration and corporate taxes.

Trump’s plans to renegotiate trade relationships with its largest trading partners — China, Canada and Mexico — and to impose severe tariffs on imports from some countries to force concessions on existing trade agreements could disrupt US trade and could be negative for sectors such as vehicles, oil and technology. But it could be positive for industries such as steel, which face severe import competition, Moody’s said.

There is also concern about how Trump might view South Africa’s inclusion in the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which gives the imports from those included preferential access to the US market. But of greater concern is that a protectionist approach to trade from the US could spark a global trade war, which

would be disastrous for South Africa as more than half of its gross domestic product (GDP) is either imported or exported, said Lings.

It’s unclear whether the election outcome will affect interest rates in the US. It’s expected Trump will appoint a more hawkish (generally in favour of higher interest rates) Federal Reserve chairperson when the incumbent’s term is up in 2018.

It’s thought that Trump’s policies will result in “later but faster” rate hikes by the central bank, and the prospect of a faster pace of rate hiking would hit South Africa in particular, said Attard Montalto. Rand volatility throughout this period should prevent the South African Reserve Bank from cutting rates.

Trump has suggested scrapping the Dodd-Frank Act, brought in to avoid a repeat of the 2008 financial crash, and has advocated a temporary suspension of all new financial regulation.

“Reducing regulatory compliance costs would support US banks’ profitability but threatens to chip away at the credit benefits of the Act — the strengthening of banks’ balance sheets and reduced risk-taking,” Moody’s said.

Trump also wants to repeal the Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare. This would be a positive for US health insurers in the long term, but an increase in uninsured citizens will be bad for healthcare service providers and medical device suppliers and will have a mixed outcome for pharmaceutical companies, Moody’s said.

Trump wants a tighter grip on immigration to increase employment among US citizens.

“His proposals would reduce the applicant pool for companies in sectors including technology, automotive and aerospace, and raise employment costs,” Moody’s said, adding that US universities would see declines in foreign student enrolment and revenues if reforms discouraged applicants.

He has also proposed lowering corporate tax rates, which he said would neutralise the benefits of holding cash overseas. “Broadly speaking, lower corporate taxes are credit positive because of the net effect of higher cash flows,” said Moody’s.

But the main beneficiaries of his tax cuts would be the very rich, said self-styled Marxist economist Michael Roberts. “Under Trump, most people would see their income tax bill reduce by about 7%, but savings for the top 1% would be about 19% of their income. To balance the federal budget, government spending would have to be cut by about 20%, hitting welfare, education and health.”

Lings said there were checks and balances that would hamstring Trump’s ambitions and the US Constitution grants only a few specific powers to the president. He can withdraw from trade policy negotiations, restart exploration on the Keystone pipeline (proposed to run from Canada to Nebraska), sign executive orders to deregulate energy prices and, as he has threatened, open trade cases against China.

“Crucially, the president needs congressional support to implement economic policies and, ultimately, the supreme court has the power to overrule any laws if they are deemed unconstitutional,” said Lings.

Repealing Obamacare, cutting taxes and building a wall along the Mexican border will require approval from Congress. He said the people Trump wants to nominate to government require Senate approval and only Congress has the power to declare war, although the president can send troops without a declaration, or issue an executive order, to undertake military action.

“Using a very simple debt model and assuming Trump got all his fiscal policy proposals approved [a somewhat unrealistic scenario], the US public net debt would increase to above 95% of GDP from about 75% currently,” Lings said.

Remember Agoa? The Donald will do things differently

COMMENT

So Donald Trump is United States president-elect. Brexit V2, only this time with nukes and a side order of sexual harassment. Nothing about this is good, unless you voted for The Donald. Let’s unpack my hysteria and try to get a grip on what this means for South Africa.

For those who have lived under a rock for the past year, let me remind of you of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) and the fireworks that were the negotiations. Flowing out of that are a few important issues that suddenly become far more relevant than before.

Out-of-cycle reviews are a thing now. They are likely to become even more of a thing, which has the potential to turn Agoa into an instrument of 50 Shades of Grey-type discipline.

Will this happen? Perhaps not, but we should not forget that the reason this particular nuance was built into the agreement was so that there would not be onlytwo options available to the US (being in or out of Agoa).

The management of the relationship has become more subtle and consequently a lot more powerful. If US industry is threatened by South African imports, we may see more of these actions.

South Africa is a lot less likely to be part of Agoa when it is next renewed. This risk could be mitigated by negotiating a full-blown trade agreement with the US, but I doubt either the US or South Africa has a huge appetite for this now. And, if we want to see such an agreement implemented, we need to get busy on that pretty soon.

I think, overall, the US will become more protectionist (although I also think this would have happened with Hillary Clinton as well). This means we could be seeing US duty increases as well as other actions such as antidumping and safeguard applications.

Even if these are not targeted at South Africa, they will still affect us. With every large market that closes, that product needs to find another home and, if the US starts to close its markets, some of that overflow will arrive in South Africa.

In turn, will this mean that South Africa then ends up bringing more protective actions?

Possibly. The recent madness regarding steel has revealed that there does appear to be some

sort of limit to how much protection the South African authorities are prepared to provide to a given sector and certainly the higher up the supply chain the industry is the less likely it is to see high duties (I may still swallow my words if the steel safeguard duties are imposed).

What will The Donald do? Only time will tell. A really short amount of time, I suspect. — Donald MacKay

Donald MacKay is director of XA Trade Advisors