Crown Totem by Bogosi Sekhukhuni

There are more than 17 people in South Africa whose work is shifting consciousness, trading narratives with the future and relieving the damned with beauty and art at the moment. Brilliant filmmaker Terrence Neale should be on this list. Artist Lady Skollie who is slaying us like she is Buffy and we are her vampires could be counted among the people on this list, as could dancers and performance artists Dear Ribane, multimedia artists Fuzzy Slippers and Simphiwe Ndzube. We see you independent publishers Phendu Kuta and Jamal Nxedlana. The creativity in the pathological playground that is our country is as diverse as the landscape is vast. But for now, here is our pick of artists and cultural practitioners who are contributing to the explosive conditions of a cultural scene that has the world looking up.

Elsa Bleda

Photographer and filmmaker

(Neon by night: An image from Elsa Bleda’s series Nightscapes)

Elsa Bleda’s photographs are a display of aesthetic inventiveness that makes the viewer go back and question everything they’ve heard described as “unique”.

Predominantly streetscapes, characterised by their just-almost-overblown but perfectly subtle saturation of artificial colours, her images provide a perfectly non-cliché vision of scenes that might have seemed ordinary to many.

Her recent work started gaining prominence in South Africa’s mainstream art world and on arts blogs globally last year after the publishing of her collection of photos, titled Nightscapes, which capture the empty streetscapes of Johannesburg’s urban sprawl in all its vivid neon glory.

She describes the city as both “Gothic’’ in a way she’d never experienced and “so mysterious”, preferring to explore the city at night when it seems abandoned and can expose parts of its true self.

The images, which sometimes resemble stills from an art-house film, have the effect of glamorising otherwise inconsequentially pedestrian spaces by hinting at the beginning of a gritty, nostalgic working-class romantic drama of some kind.

There is an eerily Lynchian feel to those suggested narratives, prompting the potential to deep-dive into something at once surreal and immediately everyday.

Music and lyrics seem to be intricately woven into her work and the titles she gives them, as well as in the way she describes the moment she captured a particular image, although she cites Japanese art director and designer Eiko Ishioka as her biggest influence, besides a fascination with sci-fi and East Asian cinema.

Bleda’s compelling work as an image-maker has earned her considerable press and this past week saw the release of her directorial debut for the remix to Kyle Deutsch’s radio single Can’t Get Enough, which exhibits her signature eerie drama and rich colouring.

The year ahead is even brighter, with an upcoming Red Bull exhibition, more motion picture projects after signing with Star Films and putting work into a photography book. — Ian McNair

DJ Lag

DJ

(Exporting gqom: DJ Lag has been introducing his bass-heavy beats to Europe. Photo: Kent Andreasen)

At the end of 2016, there were very few South Africans who didn’t know who Babes Wodumo was and what place she occupied in the South African music scene. Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan might be forgiven for being one of those few after Babes Wodumo admitted to not knowing who he was on DJ Sbu’s radio show, famously retorting: “I don’t see anything wrong in that because he also doesn’t know me.’’

A riot of a dancer turned national star and impulsively ordained the “Queen of Gqom” by her legions of fans, what many people missed about her rise is the soup she was cooked in: the gqom culture that birthed her success, originating in Durban with, among a handful of pioneers, most notably DJ Lag.

While Babes has been pushing the blown-out style of dance music into the South African mainstream, DJ Lag has been travelling abroad introducing foreign feet to the bass-heavy, experimental subgenre of house.

Last year saw him release his self-titled EP on the London-based independent label Goon Club All Stars, launching the record at a Gqom Oh! showcase that kicked off a Euro-Asia tour.

Besides touring, which sees him travel to Switzerland next month and to the Donau Festival in

Austria in April, it’s Lag’s productions that place him a head above his peers in contemporary dance music.

The upcoming video for his sleeper hit and 2016 highlight Ice Drop should propel his star further into the national consciousness, as well as a set of “interesting remixes” his management team are excited about getting out. — Mohato Lekena

Angel-Ho

Sound and performance artist

(Angel-Ho: Deconstructing gender. Photo: Jabu Nadia Newman)

The work of Angelo Valerio, AKA Angel-Ho resists easy categorization. Their artistic practice integrates two dominant elements of performance art and sound, each informing the other. Working as a producer and a club-based DJ, Angel-Ho uses sound to explore mood, experiences,and the history of club music itself. Artistic performance also features in their work as a DJ, often appearing behind the decks in elaborate ensembles.Similarly, music is a prominent feature of their performance art practice, with a pulsating track listing accompanying their work.

Through each of Angel-Ho’s chosen media, the artist delves into issues of power, resilience, and actively resists normative understandings of gender and gender presentation. Thinking of performing, they explained: “I always like to play with ideas of being packaged in certain spaces, and how I can deconstruct that idea of what people perceive from the outside.”

While 2016 may have been a difficult year globally, the last twelve months were highly productive for Angel-Ho. Notable accomplishments include their participation in the 2016 Berlin Biennial and a rousing performance at a prelude to PERFORMA 17, a pioneering performance art festival in New York City that starts at the end of this year. At PERFORMA, they and rapper Dope Saint Jude collaborated with artist Athi Patra-Ruga in a performance titled Over the Rainbow.

Last year also saw the spontaneous release of Red Devil, which the artist describes as a “soundscape of unconventional rhythms and gripping fantasy”. Later this year, Red Devil will have a physical release on vinyl, released through the African Diasporic collective NON, of which Angel-Ho is a member. 2017 looks bright. Alongside the vinyl release, Angel-Ho looks forward to the fruition of a number of projects, including a collaboration with fellow artist Quaid Heneke, and fashion designer Lukhanyo Mdingi. — Amie Soudien

Koleka Putuma

Poet

(Something to say: Koleka Putuma is capturing audiences with her powerful wordplay. Photo: Andiswa Mkosi)

“I’m sitting downstairs in my lounge. On the table I am working on are books, a wine glass, keys, coasters and random grocery slips. There are two bookshelves on my right. On top of the one bookshelf are candles, a typewriter, incense and a book about the life and work of Frida Kahlo. On the walls are mirrors, paintings and photographs. There is some sunshine coming through the sliding door. Which is rather lovely.”

Multi-award-winning poet Koleka Putuma writes to us from Cape Town, a place whose city bowels know they don’t deserve her ilk, but have produced those like her because it so desperately needs them.

It might have been after winning the PEN SA Student Writing prize in 2016 for /Water, her eviscerating homage to the relationship black people have to water and the seas, that the poet, writer, performer and theatre practitioner rose to the public’s consciousness as an intrepid envoy for the fallist generation’s collective will to #Fall everything oppressive as it stands. But her name was already synonymous with winning before that.

She spent most of 2016 refining the skills of capturing audiences, darting between stages, planes, trains and writing tables, preparing the words for her ascent in real life and on the internet.

Next month, she will stage her first theatre production, a play called Ekhaya, created specifically for three to seven year olds, about home, migration and belonging.

She’s also working on her first book, Collective Amnesia, based on a collection of poems.

It’s not difficult to become a visible creative person in the internet age. What requires skill is holding the attention of followers and critics when words are your currency and intersectional activism is the mountain you have chosen to climb without losing them with didactic raging.

Last year, Putuma sporadically started test performing and posting verses on social media written by a part of her repertoire she calls Parafeen, a misunderstood “pohet” whom Putuma says “will spark some interesting conversations around the ideas of language and representation in the spoken-word scene”.

Parafeen’s jarring English word and sentence construction is at first glance unnerving, then familiar, then extremely timely in the cultural atmosphere of decolonisation.

Parafeen’s first one womxn poyetry show is called Mothertongue Malfunxion and will debut in 2017, a year Putuma hopes to get people “to understand and respect that poetry is a craft that is time and energy consuming and that is must be paid for” with the money poets deserve instead of with “exposure”. — Milisuthando Bongela

Kelly-Eve Koopman & Sarah Summers

Filmmakers and activists

(Journey of discovery: Sarah Summers and Kelly-Eve Koopman explore their identities as coloured people in Cape Town. Photos: David Harrison)

Although they are involved in different things individually, together Kelly-Eve Koopman and Sarah Summers, a lesbian couple in their twenties, have created a six-part web series and documentary project to explore their identities as coloured people in Cape Town.

As part of this, they are embarking on a 1 000km walk led by a group of Khoi activists from Fort Beaufort in the Eastern Cape to the Castle in Cape Town, documenting the footpaths, stories and convoluted histories of this mixed ancestral heritage.

Their web series, Coloured Mentality, has become an online oasis for a conversation that has largely been inadequate on public platforms.

Coloured identity, often misunderstood as a nebulous concept or denied altogether as a legitimate identity despite being lived by millions of people, is a subject that Summers and Koopman want to unpack by questioning its faculties from inside the lived experience of being coloured.

“We believe that because millions of people recognise themselves as coloured, this identity exists,” they say.

In addition to answering the question: “What is coloured?”, asked of actors and other prominent coloured individuals who feature in the first episode of the web series, the work seeks to deepen understanding by coating this search with questions that aren’t intended to provoke conclusive answers.

These include: “What does it mean to occupy this identity? How does this identity grow? Do we understand the implications of the history of the term? Do we understand that the people that occupy this term are descendants of ancient societies? How do we correlate all the information that hasn’t been popularised to understand ourselves in empowering new ways?”

So far, the response on their 11 000-strong Facebook page and the internet in general has been “critical, celebratory, diverse and thought-provoking”, say the pair, who don’t want to be seen as the authorities on coloured or any type of identity but rather want to share their journey in the hope of inspiring and mobilising others — “because we are not alone in our search”.

Summers says she has never not thought of herself as coloured but has struggled against the stereotypes. “I didn’t want to be considered uneducated and vulgar. I didn’t want to be considered as ‘gham’. I saw myself as better than other kinds of coloured people. I was young and unsure of myself. I wanted to be defined by qualities that I am proud of, and we haven’t been taught to associate positive qualities with colouredness. This has been a process of undoing and relearning for me.”

Koopman considers herself coloured and black in the Black Consciousness sense, but has also struggled with the class differences that exist between those two socio-ideological strata. “I realise that there is a constant process of both decolonising our identities and fighting against the classism that stratifies black and brown communities,” she says, further emphasising the necessity of exploring identity in the aftermath of slave, colonial and apartheid South Africa.

The documentary, made in collaboration with Gambit Films, will begin production when they start the walk later this year. On February 4, Koopman and Summers will be hosting a fundraiser for Indigenous Liberation, an organisation of Khoi activists, as well as for the walk at Unknown Union in Cape Town. Many of the activists are artists who will be exhibiting their work at a silent auction. There will also be performances by artists Khoi Connexion and a live draw by graffiti artist Mak1. — Milisuthando Bongela

Visit the Coloured Mentality page on Facebook or watch the web series on the Coloured Mentality channel on YouTube.

Masande Ntshanga

Author

(Chain reaction: After the success of The Reactive, Masande Ntshanga is working on two more novels. Photo: David Harrison)

Author Masande Ntshanga had a busy 2016. A part of his year was spent editing his book, The Reactive, for a United States release through Two Dollar Radio publishers and then travelling to that country to promote it.

Before that was the Caine Prize workshop in Lusaka, where Ntshanga wrote a follow-up to /Space, his 2013 Caine Prize shortlisted story, and, more recently, the Ba re e ne re Literature Festival in Lesotho.

No doubt a result of its stylistic bent, primarily being more concerned with exploring human interaction than plot, The Reactive has had more legs than many recent South African novels, with publishing deals in Germany and the Commonwealth.

Two Dollar Radio also holds the film rights. Ntshanga says: “We’re looking for a director we could attach to the project. I was impressed by Necktie Youth’s Sibs Shongwe-La Mer last year — that cab scene! — and the producers at Two Dollar Radio are keen on getting in touch with him too, but we’ll see.”

In addition, 2017 should see Ntshanga completing two novels. One looks at the collapse of the homeland system, in particular Ciskei, while relying on “science fiction and an experimental structure to explore ideas around time and contemporary sexuality”.

The other, set in Cape Town, “explores the idea of the metropolis as machine”, focusing on “an impoverished urban community that awaits the return of a messiah figure — who may or may not be a false prophet — to liberate them.” — Kwanele Sosibo

Yonela Mnana

Pianist

(Emotion and rawness: Yonela Mnana transcends genres. Photo: Oupa Nkosi)

A Yonela Mnana gig is an unpredictable affair. That’s not to suggest that the singer and pianist is erratic but to illustrate the sum of influences that he draws from.

This is an artist rooted in jazz as much as he is in other musics of the black experience. Immediately clear is that he is an artist who finds the notion of genre tiresome. Having said that, there are deep traces of the avant-garde tradition in his work; impassioned bursts of emotion, original vocal phrasing and an invigorating rawness to his playing.

While Mnana may profess to have been raised on kwaito and R&B — soul, in his hand, is a roughly hewn diamond, a direct channel to the listener’s heart that almost bypasses the need for lyrics. The fact that Mnana cannot see means that he channels sound without the filter of sight.

Speaking about the title track of his 2016 album, Baba, Mnana waxes philosophical, saying it represents a three-pronged search for family, political leadership and spirituality — emotively encapsulating South Africa’s sociopolitical quagmire.

This year, Mnana is planning to produce an album for Soul Tee, a trio of voices he is mentoring, as well as master and mix his second album, a two-disc project whose recording he has almost completed. “The double album will be a solo album on one side, and the other, a trio album,” he says.

Of his trio, which includes Ariel Zamonsky on double bass and Siphiwe Shiburi on drums, he says: “We navigate all around but we still have this jazz tag on us. It informs us, in a way, it’s our point of departure.”

The solo side of the album was inspired by the work and outlook of Dumile Feni. In 2015, Mnana produced the score to accompany a series of Feni’s scrolls exhibited at the Wits Arts Museum. “I had to do a lot of research and I found out that he’d sacrificed a lot to paint in the United Kingdom in very chilly weather,” says Mnana. “And after the effort he wouldn’t even want to sell the painting, which meant that it was a very expressive approach, than just a commercial thing, which is the very same thing I’m saying that jazz is straddling — these two aspects [the commercial and the expressive].” — Kwanele Sosibo

Catch Mnana in a trio format on January 27 and 28 at Nikki’s Oasis in Newtown, Johannesburg

Paul Shiakallis

Photographer

(Debbie Baone Superpower from the series Leathered Skins Unchained Hearts — The Queens of Marok by Paul Shiakallis)

Paul Shiakallis is drawn to photographing places and objects that are “lost in time, so that if you look at the image now or 10 years from now, you won’t be able to place it”.

The feeling of being removed from reality is one the photographer holds dear. It permeates much of his work, enabling him to bring a lyricism to common social dysfunctions.

In Something So Familiar, a 2012 series Shiakallis compiled in the Unites States and South Africa, he uses the potent motif of the TV’s glow as a conduit to convey the isolation of suburban domestic life.

In Portraits of a Still Life, Shiakallis’ subjects are almost not present, their rearranged ornaments functioning as a stand-in for their personality and humanity. The photographs raise questions: What does it mean to possess material items (in this series, much of it is antiquated) and what does it speak of our relationship to time?

A Tshwane University of Technology photography graduate, Shiakallis was born in Johannesburg in 1982 to Cyprian parents.

Although he’s an accomplished commercial photographer with clients such as Coca-Cola, MTN and Mercedes-Benz, it is his creative documentary work that towers above all else.

“Removal from reality is my gravity,” says Shiakallis of his documentary practice.

“I like to stage real-life documentary, so that it momentarily removes me and the viewer from our own realities when we view the work. My lighting tends to isolate areas of a scene — though I would say that lighting is only 10% of an image. If anything is eliciting emotion, it would be the subject matter itself.”

There’s a sci-fi edge running through Shiakallis’ Leathered Skins Unchained Hearts — The Queens of Marok, a series that documents women in the Marok (metal band) scene in Botswana.

The photographer enhances this edge by allowing his subjects to turn away from the camera, or by photographing them away from the context associated with their choice of music.

Even the associated landscape photographs of Batswana villages slipping into modernity has a futuristic glint when run through Shiakallis’ outlook.

Leathered Skins has emerged as his signature work after being published in Europe and in the US by more than 35 publications.

This project will be exhibited in India later this year, alongside the work of other artists focusing on feminism at the Focus Photo Festival.

“I am looking at promoting it more locally in South Africa,” he said, “as I believe it is a socially relevant topic in the areas of freedom of speech, thought and empowerment of the individual.”

Shiakallis is currently working on a project around Hillbrow nightlife, which he says “is an exploration of how people and the structures influence the dynamic between sex, love and companionship”. — Kwanele Sosibo

Gabi Ngcobo

Curator

(Radical proposals: Gabi Ngcobo has recently been appointed curator for the 2017 Berlin Biennale. Photo: Masimba Sasa)

Despite her soft-spoken manner, Gabi Ngcobo’s curatorial and artistic practice is guided by a fierce yet considered sense of activism. This is why her recent appointment as the curator of next year’s 10th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art should come as no surprise to those who know her.

Having worked in institutions and environments steeped in apparently immovable colonialism and having witnessed the backlash that resistance to this status quo can engender, over time Ngcobo has cultivated an approach that seeks to break through the existing constraints of South African art practice.

Her singular sense of lyricism and ability to tap into and harness the zeitgeist has been apparent since her first solo and collaborative shows as an artist.

In Homecoming, her first solo show more than a decade ago, Ngcobo wove a cohesive language (using her own and her family members’ hair) to explore ideas about familial ties and wider interconnectedness.

In a pivotal group show she was involved in at that time, Ngcobo inspired 3rd Eye Vision, a collective of black artists in Durban, into a sustained state of hyperawareness and a reckoning with ancestry that culminated in the seminal Thwasa group show.

Outside the confines of the white cube, she has always examined the effect of language and the privilege of naming on the psyche of the colonised, which resulted in public debates about the etymology of Durban’s supposedly isiZulu name, iTheku. Ngcobo and her colleagues argued that it was actually called iThweke (isiZulu for a bull’s testicle).

As a curator, Ngcobo remains focused on how art practice can be made more reflective of life as it is lived by people rather than how it is theorised by a few.

“In terms of what the idea of curating can be, she presents us with some of the most imaginative and radical proposals,” says Rangoato Hlasane, Ngcobo’s colleague at the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of arts, where she maintains a teaching post.

“Her platforms have posed important questions about institutions of knowledge production and what they can look like. Her approach is about constant re-evaluation and she is always finding a new language of what we can create, to quote one of her exhibitions, ‘without panic’.

“In her work there is an awareness that we work within disciplines that have histories — but we are here in the now.”

Having cofounded the Johannesburg-based contemporary collaborative space Nothing Gets Organised with artists Dineo Seshee Bopape and curator Sinethemba Twalo, Ngcobo is proud of how it has become an open space for a new generation of South African artists.

The initiative follows other projects Ngcobo has spearheaded, such as the Centre for Historical Re-enactment.

About her upcoming role as Berlin Biennale curator, Ngcobo says: “I’m curious as to what I can effect, being someone who is interested in how institutions work. It is still early to speak about the structure [of the team I want to assemble], but I am interested in collaboration and having conversation partners.” — Kwanele Sosibo

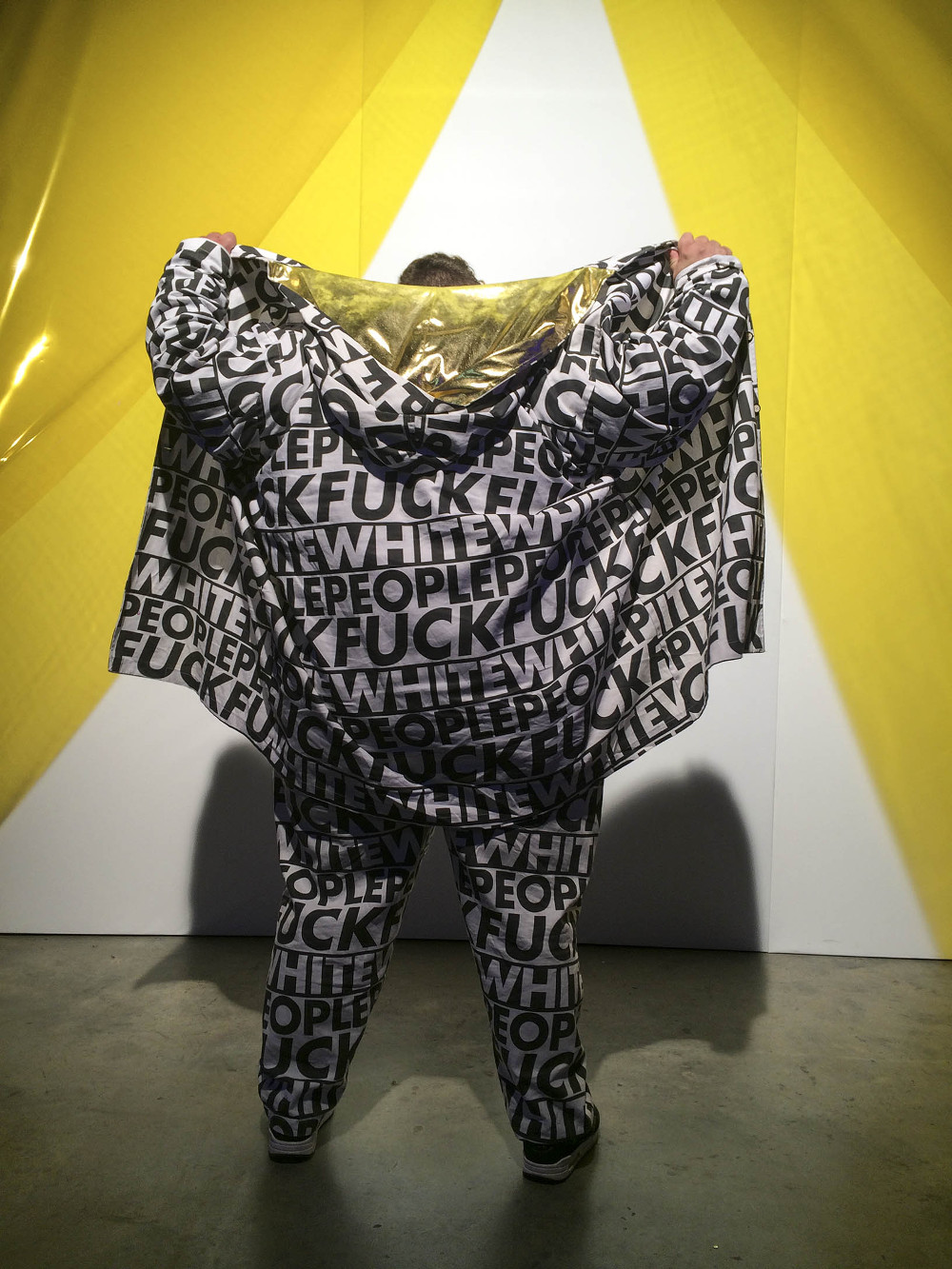

Dean Hutton

Artist and photographer

(Provocative: Dean Hutton addresseses whiteness in a work that has sparked conversations about race, art and vulgarity. Photo: Copyright Dean Hutton)

First, Dean Hutton came up against the Freedom Front Plus or VF+ who has accused them of ‘reverse racism’. Then they received angsty criticism from a former Grand Wizard of the KKK. And last week, their work, which is hanging at the IZIKO South African National Gallery in Cape Town, was defaced by conservative separatists, the Cape Party, who illegitimately pasted a red and white square sign written ‘’Love Thy Neighbour’’ over Hutton’s work.

The cause of the tension is a work that seeks to directly address the artist’s own whiteness and the toxic whiteness of society at large in the context of a local and global society that always centres the feelings, needs and wants of white people. In the work – inspired by a t-shirt that was worn by Zama Mthunzi, a black student that Hutton photographed during the #FeesMustFall protests in 2016 written ‘’Fuck White People’’ on the back and ‘’Being Black is Shit’’ on the front – the artist boldly plasters the phrase ‘Fuck White People’ on the wall and on any objects within the installation.

In a statement they released last week in response to the defacement, Hutton says the various works that use the phrase serve “as both a catalyst to start everyday conversations around white supremacy, racism and privilege and as decolonial gesture with an aim to destabilising predominately white spaces, to make whiteness visible, to reveal it’s centralised position and to perform visible allyship to anti-racism efforts to advance social justice.”

Hutton’s career before taking on the challenge of making cultural work in SA, has involved over 18 years in photojournalism, predominantly working on stories concerning society’s most underreported individuals and groups.

It was in this industry that Hutton was made angry enough about the social dynamics evident in the social structures of the country and, over the course of almost 20 years as a journalist, angry enough to take up the fight formally. Their work developed organically from still images into performance art, installations, video work and interventions, such as in their disruptive presence at Cape Town’s notoriously racially exclusive Pride celebration wearing a ‘’Fuck White People’’ three piece suit. On top of that, they have been an integral part of community organising and arts display projects, such as the #notgayasinhappy #QUEERasinfuckyou Film Festival in June 2015, and collaborations to “make work that engages beyond aesthetics,” and to “imagine creative strategies for healing so we can shift learning into care-based practices that build people rather than structures.”

For now and in the future, the self-described dissident is careful to differentiate insular art-world rhetoric and emotional activism from real-world change, “To [just] feel is inadequate, what we must strive for is a complete dismantling of the systems of power that keep white people racist, and on a daily basis reject privilege until we unlearn oppressive behaviour in ways that make us more human…” — Ian McNair

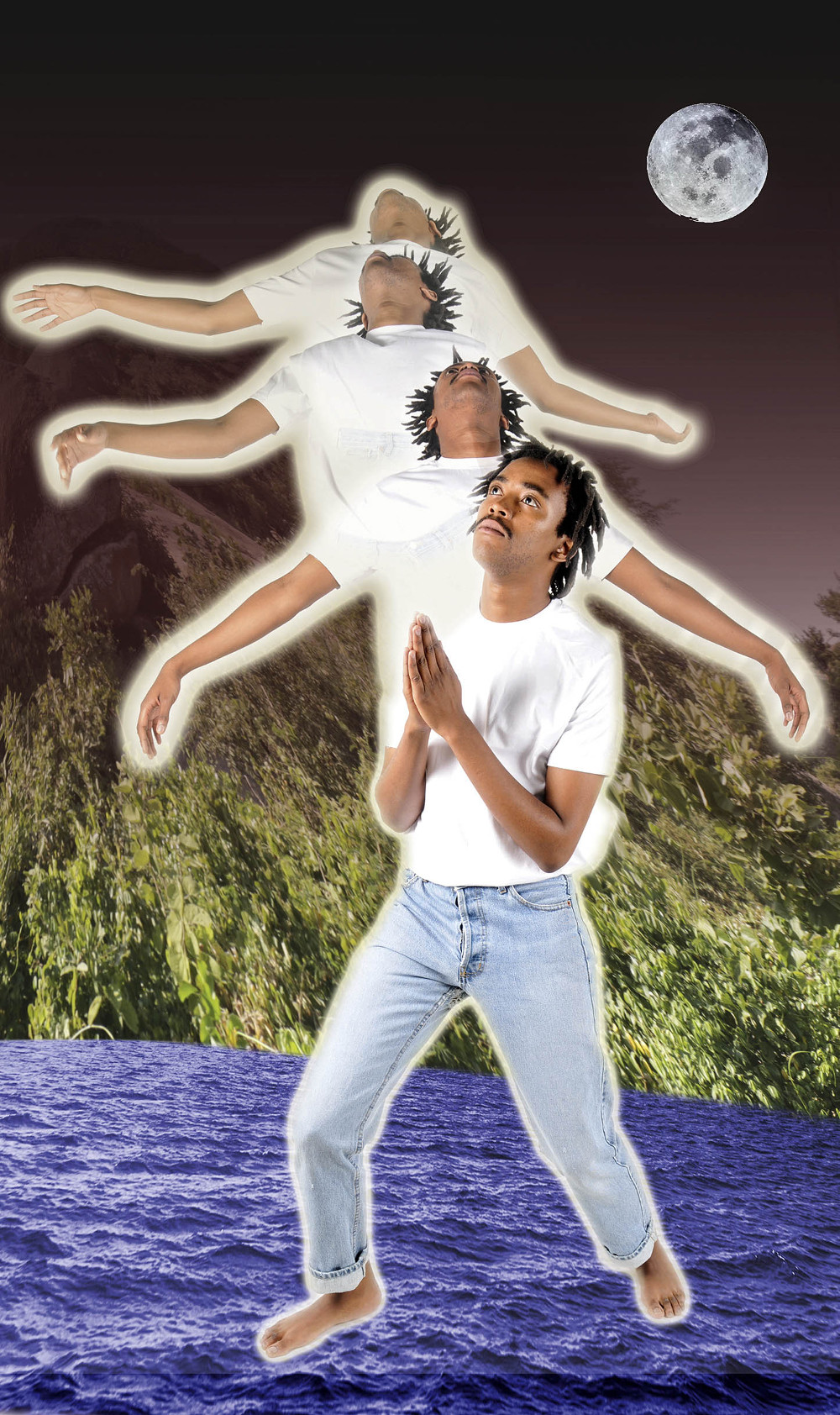

Imraan Christian

Filmmaker

(Spiritually politicised vision: Imraan Christian. Photo: Haneem Christian)

As a filmmaker whose major work is rooted in activism, Imraan Christian succeeds in visualising a future in which the oppressive structures of today have been overthrown and also depicts the pains of those with whom he identifies.

Using a deeply personal spiritualism, he has created work across the spectrum of near-future sci-fi, conceptual and documentary photography and narrative-based film photography.

He hopes for “specifically young people of colour to dream wildly, freely, beyond constraints of oppression, so that we can rebuild the truth of ourselves that has been forgotten and erased”.

Christian’s star began to rise with his globally published coverage of the #FeesMustFall student protests in late 2015.

In early 2016, he found critical acclaim and widespread audience uptake of a searing exploration of exclusion and a refreshing portrayal of skateboard escapism among Cape Town’s much-ignored youth in a co-production of his titled Jas Boude.

For the rest of 2016, he set to work creating visually affronting conceptual photography of state violence against student protest in a series titled Death of a Dream and created a multiple narrative-focused photo series reimagining portrayals of Capetonians of colour, sometimes involving Tone Society, a transformative-style collective he helped to found.

On top of that, he managed to inject his spiritually politicised vision of transformed representation and storytelling into a variety of brand content, to the obvious benefit of the subject matter and the quality and positive effect of the material.

Even as a relatively young culture-maker, Christian has a clear focus on ploughing whatever he has gained in insight, skills, access and experience straight back into other young creators of colour like himself.

He hopes the audience sees that his work is “merely at the forefront of an awakening generation”.

The work of this generation, and his own work, is clearly a deeply personal “process of catharsis and self-exploration” that “is replacing colonial constructs with something that is true to ourselves”, driven by a desire to imagine “what we would create if we were truly free”. — Ian McNair

Sbucardo da DJ

Gqom producer

(Gqom innovator: Sbucardo at his home in Inanda near Durban. Photo: Matt Kay)

In current gqom discourse, Sbucardo occupies something of a liminal space that has nothing to do with the music’s success in Europe and its reformatting locally.

Widely considered as one of the genre’s stylistic innovators — perhaps the single most notable Sbucardo contribution to the genre is his trademark spliced vocal sample, a trick he invented using the distinctive voice of Durban kwaito legend Mampintsha.

In a sense, this was Sbucardo’s signal to the world just how the underdogs would overturn Goliath’s reign by using his own tools.

So if you observe the concerted moves Mampintsha’s West Ink Records is making to gain a foothold in gqom, know that to a degree this is Sbucardo’s legacy.

These are the fruits of his tireless criss-crossing of small-town KwaZulu-Natal and, increasingly of late, the entire country.

Listening to some of his recent uploads, Sbucardo da DJ seems to have been tinkering with his own formula, moving away from the edgy syncopated sound of his past into a more four-to-the-floor aesthetic, as if chasing his own tail.

“That’s not entirely true. I have been upgrading my studio and to put out the gqom sound I am known for, I have to be able to hear those kicks loudly and clearly. 2016 was a little difficult in the sense that I was working in other people’s studios, while putting together the capital for the upgrade,” he says.

For 2017, Sbucardo lists a host of talent he will be working with, including producers and even R&B singers. Mark this year as the return of the shadowy Sbucardo. — Kwanele Sosibo

Bogosi Sekhukhuni

Artist

(Crown Totem by Bogosi Sekhukhuni)

Bogosi Sekhukhuni has always made work that appears to be sci-fi, constructing near-future visions of how localised culture and interpersonal dynamics might look if the politics of the near-past or current epoch were allowed to persist or be destroyed.

To Sekhukhuni, science fiction is “less about predicting the future and more about acknowledging the extreme present, but also fantasising and imagining. Innovation can come out of that.” Much of his work uses cutting-edge technology or networks and aesthetics popular on the left-of-centre web.

Through powerful, humour-tinged internet-driven works from 2014 onwards, Sekhukhuni has made a refreshing impact on an unsatisfying and technically archaic conversation around identity politics and South Africa’s contemporary cultural condition.

Part of this work included developing dad bots, critiquing white South Africans’ underhanded insultliments (an insult disguised as a compliment) to people of colour and drawing on cultish religious symbolism and Tumblrisms to install his ideas of himself and those he identified with into globalised virtual worlds.

Through his work with artists’ collective CUSS, 89plus (an international platform that fosters artists born in, or after, 1989) and NTU, he has pushed his work into a certain kind of futurism, but never at the risk of being ahistorical. His research group, Open Time Coven, purports to do the ostensibly disconnected work of “investigating emergent technologies and repressed African spiritual philosophies”.

This has, it seems, been building up and refining towards a richer, more refined and congruous narrative that will no doubt be demonstrated in his first Stevenson gallery solo show next month, titled Simunye Summit 2010, something he describes as both “the closing of a chapter and a new beginning” in his work.

This new work has been driven by an exploration into South African Defence Force “covert operations into biochemical warfare that developed in the 1980s, in particular the chemical warfare laboratories under Project Coast”.

He has continued to explore many of the narrative threads of his earlier work, but explains: “I’m trying to unpack some of these concepts in real applicable ways to my practice. I’ve been in a process of healing and recovery and that’s something I feel needs to be recorded, to generate more conversation around this state of being a lot of people go through.” — Ian McNair

Simunye Summit 2010 is on at Stevenson Johannesburg from February 2 to March 4

Mbali Dhlamini

Visual artist

(Artist Mbali Dhalamini uses church uniforms’ colour palettes to explore African Christianity. Photo Oupa Nkosi)

Since 2014, Mbali Dhlamini, a fine art master’s graduate from Wits, has been looking at the role of colour in the Africanisation of missionary Christianity, with a particular focus on the African independent churches.

Over the years Dhlamini has produced work that looks at the liminality of these churches, juxtaposed with the omnipresence of church uniforms from various groupings.

In Non promised Land: Bana ba thari entsho, which she exhibited in 2015 as part of her master’s programme, she presented pastel drawings depicting the garments framing headless and limbless bodies, in an exploration of how the garments were used in the creation of personas.

“The women and men wearing these garments would do so differently,” says Dhlamini, “like they were supreme beings. It gave them isizotha (a quiet dignity). I didn’t grow up in a church where people wore the dresses so I was always curious about the designs, the colours and some of the symbols that they attach to the garments. My first interest was in the colours.”

She has also presented installations of clear plastic approximations of the attire, with related drawings, pointing to their importance, even as their owners escape the physical plane.

“I’m moving on,” she says. “I want to look at colour among different language groups within the Ki’ntu classification. With different languages there would be different names to call colours and different meanings.

“There are so many vocab notes that are related to it and they carry different meanings, like how they [colours] are used in Zulu love letters, and how they are still used in independent African churches.”

To this end, Dhlamini is working on a series of silkscreen prints at Artist Proof Studios in Johannesburg with the printer Charles Kolobeng.

Currently unburdened by ties to a specific gallery, in 2017 Dhlamini nonetheless has clear aspirations for more visibility.

“I want to show in all of the fairs that are happening this year, be it in Jo’burg or Cape Town,” she says. “And I am looking at getting a studio and doing more projects from my studio.” — Kwanele Sosibo

Phumlani Pikoli

Author and filmmaker

(Writing in many formats: Phumlani Pikoli just wants to express himself creatively. Photo: Tseliso Monaheng)

When not photographing food or themselves, millennials have spent the finest years of their youth being the punchlines of jokes by older generations who just don’t get their darned ways.

Often-used lines of attack focus on a perceived inability to focus, an annoyingly intractable belief that anything they put their minds to is possible, and a proliferation of the offspring of these two notions: the “side hustle”.

Phumlani Pikoli’s résumé reads like a hyperbolised example of this. He’s been credited as a journalist across a variety of subject matter, a playwright, an author, a digital platform manager and editor — with all gigs performed with a cohesion of style and rigour that quickly debunks any characterisation of millennial laziness.

Pikoli is, foremost, a creative mind whose main output involves writing and from that basis he can, and does, take his craft anywhere.

His latest project began as the remarkably considered self-published book The Fatuous State of Severity, which has began morphing into something more.

The collection of short stories, a well-received collaborative work with illustrations by close friends such as 2016 FNB Art prize-winner Nolan Oswald Dennis, was written as a form of therapeutic catharsis while Pikoli was undergoing treatment for depression.

This year the book has spawned a film, shot and scored by affiliates in the same collaborative manner as the book.

The project, in his own words, is a “multidisciplinary anthology, more than a book released by one person”.

The book and movie have so far included work with contemporaries Fuzzy Slippers, Skhumbuzo Vabaza, Tseliso Monaheng, Dennis, Pola Maneli, Nas Hoosen and more.

Pikoli has similarly large-scale plans for 2017. First, he plans to complete his novel /Born Freeloaders, about “black kids growing up in middle-class suburbia in Pretoria, and the influence of different forms of privilege”.

Then he has plans to stage the sequel to a play he wrote at age 22, titled /Imperfect Draft 1, which was performed in 2010 at the Amsterdam Fringe Festival, and also to produce digital features on a range of pertinent local themes.

Pikoli sees each thread of the work he’s involved in as tied to one central idea: “I just wanna write and express myself creatively, whether that be on paper, on stage, in film or in digital.” — Mohato Lekena

Buhle Ngaba

Actor, author and theatre activist

(Buhle Ngaba: ‘The lens through which I work is telling the stories of women of colour.’ Photo: Neo Baepi)

Like many of her contemporaries, Buhle Ngaba is immersed in multiple modes of creative expression that produce a visibility and voice concomitant with the age of the rise of the modern black woman practitioner.

This combination of attributes means one can’t and usually doesn’t just do one thing. This 25-year-old’s hands are full.

Ngaba studied acting and contemporary performance at the University Currently Known as Rhodes (or what some prominent academics call Cecil’s College), the process of performance at the University of Leeds and was the first black woman recipient of the Brett Goldin Bursary, which resulted in a residency at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, England.

But it wasn’t her stage endeavours that beamed Ngaba into the scene of the virtually visible — it was a children’s story that she accidentally wrote and published in 2016, The Girl Without a Sound.

“Accidental” because she meant to write a five-page children’s book to give to her aunt as a birthday present. When she told her friends about the story she had written, they also wanted copies and the rest is a downloaded-45 000-times tale.

Perhaps the reason for the book’s success is the intentionality of the writer’s approach. “The lens through which I work is focused on telling the stories of women of colour, as our voices are not heard and finding echoes of ourselves in history books is impossible,” she says. There are plans to translate the book into several indigenous languages.

For the 2017 theatre festival circuit, Ngaba is in the process of developing The Swan Song, a one-woman show she wrote on odd afternoons when she would stare at the swans on the River Avon. It’s a story that plays on the meaning of swan song both as an elegy to Goldin (a promising actor who was murdered in Cape Town in 2006) and as metaphor for pain and love lost. The show premieres at Klein Karoo National Arts Festival in Oudtshoorn in April. At the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in June, she will present a two-woman show that she is developing with another director.

In the spirit of wringing out all that she absorbed in Stratford, Ngaba is piloting workshops called Shakespeare Grounded with the aim of making William Shakespeare’s writing accessible to children who have never been exposed to his work. This she is doing through her production company KaMatla Productions.

“My feeling is once kids can comprehend the elements of a story through experiential learning, then they can begin to comprehend how all great classics are only named as such because they tell a basic story of what it is to be human. Flawed and all,” she says.

“Once you grasp this, you begin to realise that Romeo and Juliet are the equivalent of Sipho and Jabu who live in a township, fall in love but can’t be together because their families have been in taxi wars for centuries.”

Ngaba says she works from a place “of wanting to contribute to a movement (led by women of colour) to a world where we are seen and heard”. — Milisuthando Bongela