Klaas Priega tells the story of the man who cursed the wind at Vanwyksvlei.

The Man Who Cursed the Wind and Other Stories from the Karoo by José Manuel de Prada-Samper (African Sun Press).

One of my favourite South African books is Specimens of Bushman Folklore by Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. Published a little over 100 years ago, Specimens is a delightful collection of stories narrated to Bleek and Lloyd by former Bushmen prisoners in Cape Town in the late 1880s.

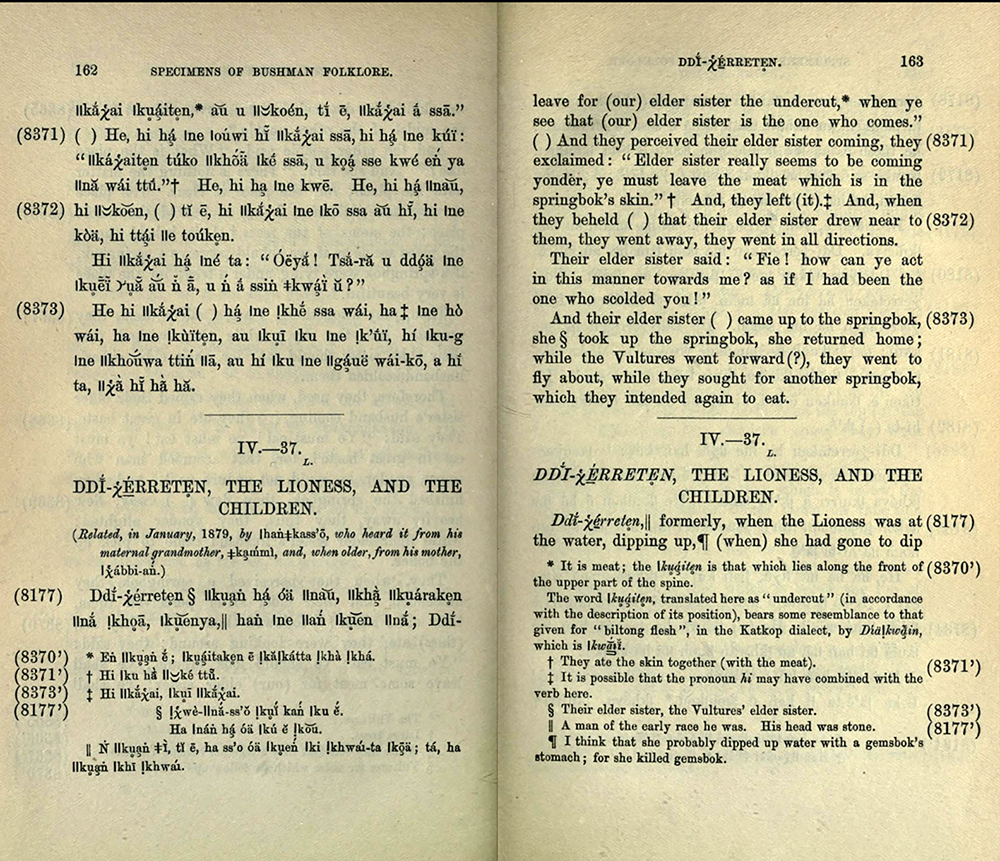

But, as enchanting as the stories are, there is something that always stops me when I open the book. It is written in two languages, side by side, /Xam on the left and English on the right. To be able to collect the stories of //Kabbo, Dia!kwain and others, linguist Bleek and his sister-in-law Lloyd first had to devise a system to write /Xam, including its complexity of clicks.

But it is extraordinary that the /Xam text came to be included in Specimens. There were never more than three people who could read /Xam: Bleek, Lloyd and Dorothea Bleek, Wilhelm’s daughter.

I asked José Manuel de Prada-Samper, the author of the recently published The Man Who Cursed the Wind and Other Stories from the Karoo, about this. He confirmed that Dorothea is known to have been able to read /Xam as she translated some of Lloyd’s notes in /Xam into English.

De Prada-Samper and I were drawn, albeit at different times, to the Bitterpits, somewhat south of Kenhardt in one of the harshest parts of the Karoo, a landscape already defined by harshness. Here //Kabbo, Bleek and Lloyd’s principal interlocutor, had grown up, collected and told his stories.

José Manuel de Prada-Samper. (Joaquín de Prada)

De Prada-Samper, a folklorist from Barcelona, had come to the Bitterpits after discovering the Bleek-Lloyd archive, 12?000 pages of narratives, personal stories and descriptions of rituals, beliefs and customs, which the pair compiled from 1870 over a 12-year period. Housed in one of the libraries at the University of Cape Town (UCT), it is recognised by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) as one of humanity’s essential archives.

My own quest, from frequent trips through the Karoo, often on a bicycle, had become to find people who still at least part-owned the identity of the first people of the country. But I didn’t even really know how to phrase questions to find this out.

I came in time to think that perhaps the approach was to ask whether anyone knew stories from the old times, when lions and other wild animals still roamed. I would be told yes and pointed to likely storytellers, but both on my bike and in follow-up trips by car, never actually managed to get anyone to tell such a story.

The reason is simple: you cannot just pitch up and ask to be told stories. De Prada-Samper, I gathered from the stories of Nak Reichert, the owner of the farm that incorporates //Kabbo’s Bitterpits, had aeons of time. He could spend the whole day on one of the rocky outcrops, some glistening with animal engravings, just lying looking into the sky, Reichert told me.

Where Reichert knew every bush and plant and delighted in sharing his knowledge, De Prada-Samper could offer a story that referenced this fauna.

Reichert had found //Kabbo’s living site, this later being confirmed by archaeologist Janette Deacon, who did the definitive research work in the area.

Reichert showed me where makeshift huts had been secured by a circle of stones. A set of grindstones — large stone for the base, smaller stone on top — were still in place from when the last stories were told here nearly 150 years ago. Then //Kabbo’s people had upped and left.

“Can you feel it?” Reichert related that De Prada-Samper had said at the site, a reference perhaps to spirits past. I couldn’t, but I knew I was in a sacred place.

De Prada-Samper writes that on a March 2011 trip to the area he decided there was no harm in trying to conduct a few interviews with “farmers and farm labourers, especially the latter, since many of them, even if they speak only Afrikaans, are almost certainly direct descendants of the /Xam”.

There was little reason to think that the interviews would produce results connecting the present to the past. Dorothea Bleek visited the area in 1910-1911 and found people who could speak /Xam but “not one of them knew a single story … the folklore was dead, killed by a life of service among strangers and the breaking up of families”.

But 100 years later, De Prada-Samper listened to a storyteller, Magdalena Beukes in the township of Brandvlei, tell stories including one she called Ouma and the Lion.

Ouma had got stuck to the floor because she really didn’t want to get up. Her body grew stuck to the ground. They could not pull her up because, by doing this, her body might break in half at the waist. They decided to move, to leave Ouma, to see whether a lion would come and eat her.

The lion came. Ouma grabbed the beams of the roof, but her legs remained stuck. The lion ate her legs. Then he ate the rest of her.

Brandvlei: Magdalena Beukes (left) tells the story of Ouma and the lion.

De Prada-Samper recognised the story as one previously recorded by Bleek and Lloyd, variants of which were narrated by //Kabbo, Dia!kwain and two others.

“There before us was living proof that Dorothea’s tidings of the demise of the /Xam storytelling tradition were quite premature,” he writes, saying this “challenges our perception of the stories and testimonies in the Bleek and Lloyd collection as the closed corpus of a vanished literature”.

That he was to recognise the story at all is evidence of his encyclopaedic knowledge of this material. I have read extensively in the archive, all of which has been digitised and is online, as well as a host of secondary material, but if Beukes had told me the story of the Ouma and the Lion, to me, I would not have recognised it.

The Man Who Cursed the Wind takes its title from a story told by Klaas Priega at Vanwyksvlei, which marked the southern end of //Kabbo’s territory. A man made a fire to harvest honey to make beer. The wind came up, and the smoke made him cough. He cursed the wind. It turned him into stone.

“Well then, my grandfather told me then, as my grandfather told me then, that rock still stands on that farm, in the veld,” Priega said. “It still stands there.”

De Prada-Samper sent me a photograph of the personlike rock jutting out from near the top of the otherwise rolling Kareeberge, just south of Vanwyksvlei. He records in Cursed that in 1875 Dia!kwain told Lucy Lloyd a different story about the rock person. A man was playing a goura, a traditional instrument. A maiden in ritual seclusion looked from her hut to see who was playing the music; the man was instantly turned to stone.

Specimens of Bushman Folklore (1911) has /Xam text on the left-hand page and English on the right.

Cursed has an extensive introduction co-written with UCT archaeology department head Simon Hall to contextualise the stories, but otherwise is mainly a showcase of the material collected by De Prada-Samper both where the Bleek and Lloyd storytellers lived and wider afield. A short note accompanies each story giving details of the storyteller — there are 29 in all — and where it was recounted.

The stories reach back in time. Most of these storytellers are not young; their stories in some cases were learned from their grandparents. They are grouped into people of the past, a long time ago, the time of the lions, not so long ago, animal tales, jackal and hyena stories, stories about animals and people, water snakes and ghost stories.

There are also stories of the master outlaw, accounts of Dirk Ligter and other famed, sometimes fabled, sheep thieves who were always at least one step ahead of the law.

There are stories about foot-eyes, people who do not have eyes in their heads, just in their feet — they stand upside down to be able to see anything; of animals that can talk (of course); lions are well represented, but so are hyenas, jackals, wolves, baboons, as well as the odd porcupine, tortoise and owl.

“The language of the /Xam people interviewed by Bleek and Lloyd is now, at best, only a vague memory, although some of the storytellers told me that their grandparents or great-grandparents still spoke it, and that they themselves remembered the odd word or phrase,” De Prada-Samper writes.

“In spite of the loss of language many, although certainly not all, of the stories they tell belong to the larger Khoisan tradition that encompasses the /Xam narratives recorded in the 19th century.

“A number of stories show a strong European influence, even if they have been, to a large extent, adapted to local circumstances and mores.”

De Prada-Samper lets the material speak for itself, but provides context where similar stories have been recorded. Some are widely known in Southern Africa, many are known in Europe but have been Karoo-ified into the local vernacular of sheep stations and skerms (a windbreak made from bushes).

De Prada-Samper says Cursed is but a sample of the stories he has collected and continues to collect. They number in the hundreds. “As Lucy Lloyd did in 1911 when she published Specimens of Bushman Folklore, I too aim to offer a representative selection of what I have gathered in the four years of intermittent fieldwork. Unlike Lloyd’s book, however, this one is not only meant for scholars, but above all aims to reach the storytellers themselves and the communities in which they live.”

To facilitate this, Cursed is written in two languages with facing pages in English and Afrikaans.

True to his word, as part of De Prada-Samper’s book launch he drove around the Karoo to give copies to his storytellers, recording a YouTube slideshow of this trip.

Unhappily, he was to learn on the trip that Reichert, the caretaker of the Bitterpits for many decades now, had died.

I had mentioned aspects of the /Xam story to fellow cyclist Steve Pike while riding in the Cape. Pike and I had something besides cycling in common; we had spent a year, although at different times, at Harvard University as part of the Nieman programme.

Archaeological digs were under way in Harvard Yard while Pike was there, and he found himself intrigued by the project.

The university had originally been founded as a multicultural institution, its founding document from 1650 being dedicated “to the education of the English and Indian youth of this country in knowledge and godliness”.

An Indian College to house 20 students was built in 1655, and the digs in Harvard Yard found the remains of the college and numerous artefacts from the period.

A printing press had been set up in the Indian College and a method to write the indigenous Algonquin language devised by John Eliot, a Massachusetts missionary who published an Algonquin version of the Bible in 1663, the first Bible to be published in North America.

Algonquian is a broad grouping. The tribe inhabiting what became known as New England was the Wampanoag. The tribe members were decimated by diseases brought by the settlers, the English-Indian war of 1675-1676 and being sold into slavery, their numbers reduced by as much as 90%.

Pike told me about a Native American, Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk, who graduated from Harvard Indian College in 1665. “The next Wampanoag to graduate was Tiffany Smalley, who was in my class in 2010!”

For 150 years the Wampanoag did not speak their language, but starting about 20 years ago they have been reclaiming it, constructed from historical documents written in Algonquin, including the Eliot Bible and title deeds from the time of the first settlers. This story is told in the uplifting documentary We Still Live Here. Today, the Wampanoag can once again speak their language.

De Prada-Samper has activated a process that in time could see a similar reclamation of /Xam, a day when descendants of the /Xam storytellers could read the story of Ouma and the Lion on the left-hand page, the one written in /Xam.

Kevin Davie will co-teach a course in South African narrative non-fiction as part of the Wits Journalism programme in the second semester of this year.