Through world wars, economic depression, apartheid sanctions and global financial crises, the South African equities market has offered investors the best returns over the past century.

This is according to research published by the Credit Suisse Research Institute and London Business School professors Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton.

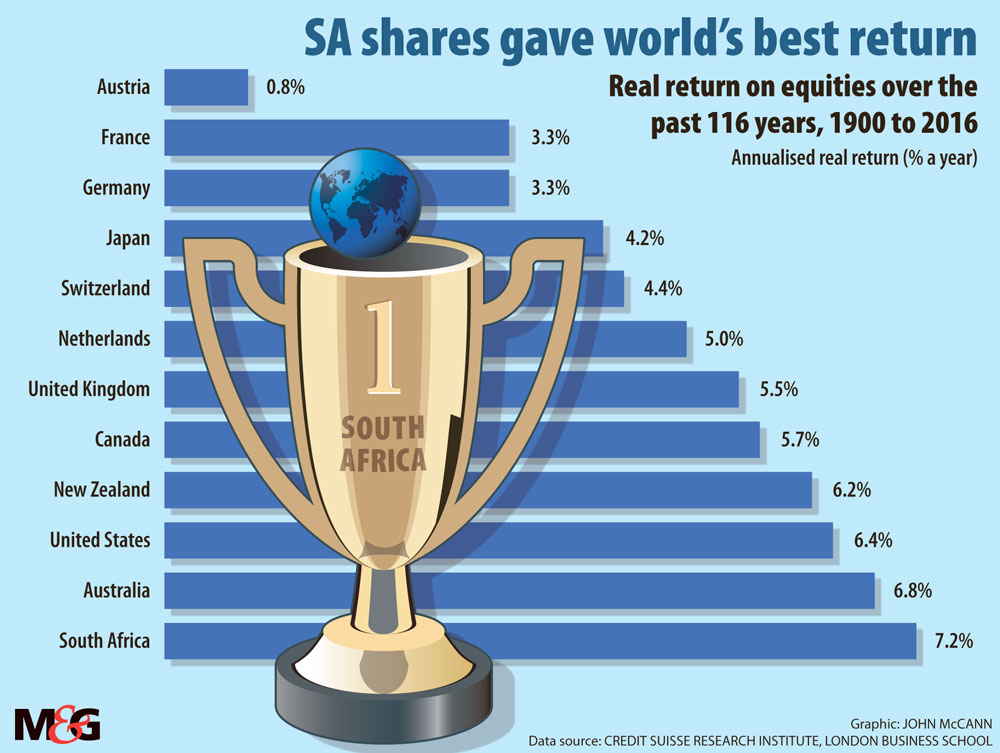

The report found that, between 1900 and 2016, the annualised real return on South African equities was 7.2% a year, beating 23 other countries surveyed.

But this momentum may not be retained into the future, say analysts.

South Africa’s performance outdid the likes of nations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan. By market capitalisation, however, other stock markets dwarf South Africa’s JSE, with the US share of the global stock market at 53.2% in 2016.

Other resource-rich countries such as Australia and Canada have done comparatively well, according to the research, chalking up returns of 6.8% and 5.7% respectively in the past century.

In more recent times, between 2000 and 2016, local equities did even better, providing real returns of 8.2%, topping Denmark, which comes in a close second at 8%.

There are a range of reasons why South Africa has performed the way it has during these periods, according to local analysts.

A century is long time and any number of factors, crises and events could shape investment performance, said Citadel investment analyst Nishlen Govender.

The key driver of stock returns in South Africa, at the start of the 100-year period and its end, has been resource shares, he said.

“The index was created as a way to provide liquidity and capital to, among others, gold, platinum and diamond producers. So the start of the 20th century was a period of fantastic growth for both the South African economy and equity markets,” said Govender.

This carried the country for some time, but things came undone when the gold standard was abandoned and during the turmoil of sanctions imposed under apartheid in the latter part of the century, said Govender. Nevertheless, this early period of strength bore the country into democracy and the significant boom of the new millennium, he said.

Others say the performance of the JSE over the past 100 years is the result of companies beyond the resources realm.

JSE performance has not been linked simply to the performance of the South African economy, said Patrice Rassou, head of equities at Sanlam Investments. It is also the result of good performance “across the board from resources, industrial and financial companies”.

“Many of these companies withstood periods of economic slump and performed well with sanctions in place. They built globally competitive businesses and were able to compete internationally once sanctions were lifted,” said Rassou. A good example was SABMiller. Founded in 1895, it grew to become one of the world’s largest brewers before being bought out by Anheuser-Busch.

But the period between 2000 and 2016 “is a truly interesting one”, said Govender.

A number of scenarios have played out during this time, he said, including the dotcom or technology bubble, the commodities surge, the great financial crisis and a significant bull market in equities after the recession, as central banks used accommodative monetary policy to assist financial markets.

With the exception of the financial crisis and the dotcom bubble, these events had a positive effect on South African equities for different reasons, resulting in a truly phenomenal period for South African equities, according to Govender. Even considering the tech bubble and financial crisis, South Africa was relatively well insulated from both, leading to somewhat muted effects on returns, he said.

The commodity bull market allowed South African firms to benefit from rampant increases in the gold and platinum price, among others.

Accommodative monetary policy following the recessions led to a significant hunt for yield, which benefited emerging markets, said Govender. This was particularly good for South Africa, which benefited from bond and equity inflows from international investors owing to its sophisticated financial institutions and markets, he added.

“In a variety of ways, South African financial markets have been extremely fortunate over the past 16 years and this is apparent in equity market returns,” he said.

Another key factor, if not the best explanation for the performance of South African equities in the past 16 years, is company valuations, according to Rassou.

In the early 2000s, local firms were valued on price to earnings (PE) multiples of about six to seven, whereas their developed country counterparts’ PE ratios reached stratospheric levels during the height of the tech bubble, said Rassou. South African firms were about 75% cheaper than their developed market peers.

The JSE has performed relatively well in recent years, even as the South African economy more broadly has struggled to grow, as a result of major firms with dual listings.

The JSE’s stock market is three times the size of the domestic economy because of dual-listed companies and the fact that many domestic companies have sizeable businesses elsewhere, said Rassou.

There has always been a large proportion of the index that has benefited from what has been happening outside of South Africa’s borders, said Govender.

Dual-listed and rand hedge stocks, or firms that receive a large part of their earnings offshore, dominate the FTSE/JSE All Share Index. These include the likes of Naspers, BHP Billiton, Anglo American and Old Mutual.

“The recent past has been a poor period for South Africa from an economic perspective and this merely magnifies the weight of non-South African companies in our index, making them the vast proportion of index returns,” said Govender.

Future returns will not mirror the real returns enjoyed over the long term, said Rassou. Valuations are not as depressed as seen in the past, he said. With global growth below par and interest rates yet to normalise, “more muted returns” are likely, he added.

But there are parts of the market able to grow faster than the economy over the long term, he said, such as small caps or companies with an expanding global footprint. An example is Steinhoff, which listed internationally last year and began making acquisitions in the UK, Europe and US.

How to tap into JSE perfomance

A cost-effective way for retail investors to tap into the JSE’s performance is to buy an exchange-traded fund that tracks the FTSE/JSE All Share Index, says Citadel investment analyst Nishlen Govender.

But this strategy comes with risks, notably market risk, which an index fund is unable to manage, he added.

“In other words, you would be invested in the particular fund or index through crashes, style swings and so on, unless you took active decisions to disinvest at certain points,” said Govender. There are a variety of ways to represent an index based on the way the constituents are made up, he added, and the choice of methodology used will directly relate back to the investment’s performance.

Instead of wondering how billionaires such as Patrice Motsepe or Christo Wiese are investing their wealth, you could invest in their companies alongside them, suggested Sanlam Investment’s head of equities, Patrice Rassou. But he warned that there are always risks involved; it’s better to invest in a number of stocks rather than one or two.

A unit trust or pension fund should give investors this necessary diversification, allowing an individual access to a portfolio of quality businesses, he said.

“The biggest mistake an investor can make is not to save regularly and benefit from the power of compounding,” he said. In all cases it is advisable to enlist the help of a professional.