Nuclear energy is 16% more expensive than the most expensive type of coal electricity production

NEWS ANALYSIS

South Africa’s credit rating downgrades to junk status are a blow to the government’s nuclear ambitions.

This is according to economists and international nuclear industry experts, who said it was highly unlikely that the state, under the purview of beleaguered utility Eskom, could afford to build nuclear plants at the 9 600 megawatts it has planned.

If nuclear procurement went ahead regardless, the likelihood was “very high” that the South African economy “would be badly hurt”, said Mycle Schneider, the lead author of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report (WNISR).

Despite concerns about the state’s ability to finance nuclear power initiatives, President Jacob Zuma’s recent Cabinet reshuffle has been seen as clearing the way for accelerated nuclear procurement. The reshuffle prompted ratings agencies S&P Global and Fitch to act, whereas Moody’s has placed the country on review for a further downgrade.

In its decision Fitch noted that, under “the new Cabinet, including a new energy minister, the [nuclear] programme is likely to move relatively quickly”.

Russia is believed to be among the frontrunners in South Africa’s procurement plans.

But the financial muscle of vendor states such as Russia to help the government finance nuclear expansion has also been questioned.

Russia has, through its state nuclear conglomerate Rosatom, helped to fund other nuclear projects internationally. But in 2015, as the Russian economy sank into recession, credit ratings agencies downgraded it.

The likelihood that two junk-rated economies would engage in a multi-billion dollar investment was “virtually zero”, Schneider said.

In the case of Russia’s rating from Moody’s, the outlook on its sovereign debt improved early this year to stable, but its rating remains sub-investment grade.

This also applies to the likes of JSC Atomenergoprom — Rosatom’s nuclear construction firm — which Moody’s has rated at Ba1.

“Russian proposed financing schemes for nuclear power projects in South Africa and many other countries would stretch Russian state finances way beyond its capacities and are therefore hardly credible,” said Schneider.

This is in light of the scope of Rosatom’s announced projects, about which Schneider said he and nuclear industry analysts were sceptical.

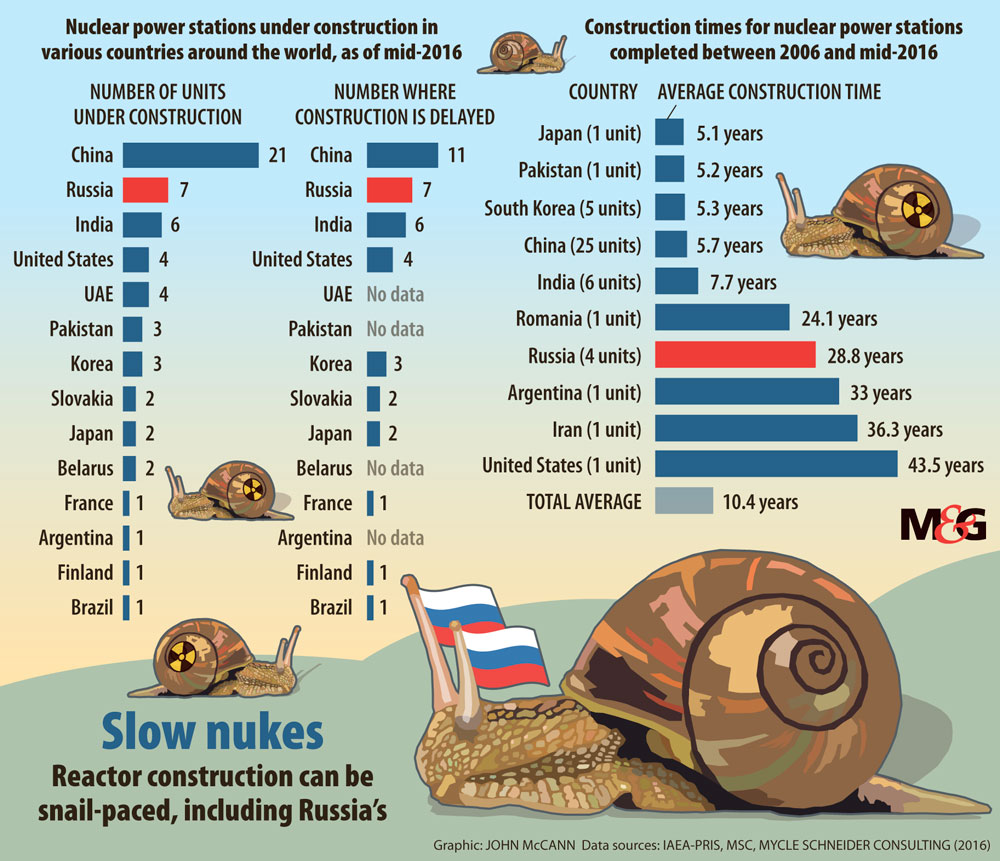

As with numerous other nuclear vendors, Russian nuclear construction projects both internationally and in Russia have faced delays.

According to the latest WNISR, released mid-year last year, all seven nuclear reactors under construction in Russia are delayed, with two units stalled for more than 30 years.

Schneider said that, although one additional reactor has started up in Russia in the interim, it was the exception, and had a construction period of eight years. All the remaining units under construction are behind schedule.

Moody’s said in February that JSC Atomenergoprom’s rating was constrained by, among others, “the challenging operating environment expected for Russian companies” and the “execution and political risks” from the company’s growing nuclear unit construction business overseas. Moody’s added that positive pressure on the rating was unlikely in part because of inadequate liquidity.

These changes in the plans for nuclear procurement are in line with public statements by Eskom’s nuclear head David Nicholls, who told EE Publishers in January that the utility would like to have a request for proposals (RFP) for nuclear procurement out by mid-2017 and the evaluation of vendor offerings completed by the end of the year.

Eskom spokesperson Khulu Phasiwe confirmed this, saying the release of an RFP would depend on approvals being obtained.

The sovereign downgrade by S&P and Fitch has financial implications for Eskom.

Eskom’s credit rating is closely related to the sovereign. Fitch downgraded Eskom’s rating to junk to bring it in line with government’s rating. Eskom is highly reliant on the

R350-billion in government guarantees to raise capital and it was issued with a R23-billion cash injection in 2015.

The downgrade “is the single largest blow to the nuclear project”, said Iraj Abedian, chief executive of Pan-African Investment & Research.

It was financially “near impossible” before the downgrade but since the ratings action was “more than impossible”, he said.

Despite political pressure to push it through it would be “simply stupid” for any foreign funding agency to “bank [on] getting paid over the next 30 or 40 years,” Abedian said.

He believed that in South Africa’s nuclear programme Russia, France and Japan could play different roles but, irrespective of this, the game had now changed. He was sceptical that the government would find funders for the project “even on geopolitical grounds”.

Abedian argued that Russia was “in no shape” to finance a long-term project of this nature.

“Furthermore, with the credit lines of the banking sector downgraded, our banks are in a much weaker state to get involved in such long-term and indeterminate funding,” he added.

In the aftermath of the downgrades Enoch Godongwana, the head of the ANC’s subcommittee on economic transformation, said an economic recession was “a possibility”. He added that the government and the ANC had adopted a policy of expanding nuclear energy by 9 600MW under the 2010 integrated resource plan (IRP2010) — the road map for South Africa’s energy mix into the future.

But “conditions have changed, which may necessarily mean we may have to relook at that”.

He noted that the ANC has said more recently that nuclear procurement must happen at a pace and scale that was affordable.

In its recently published policy documents, which the party released ahead of its policy conference in June, the ANC said nuclear power generation should be “based on the requirements of affordability, as well as procedural fairness and transparency”.

Nuclear energy plans entering tender processes now were from “before we had entered junk status”, said Godongwana.

“Surely in the light of junk status, we will have to sharpen our pencils and revise our expenditure patterns as government,” he said.

Eskom has issued an initial request for information (RFI) which closes at the end of April, and may issue an RFP by mid-year — but this is being done on the basis of the IRP2010.

The policy document is notoriously outdated and does not cater for major economic changes in recent years, such as plummeting electricity demand or the rapidly declining costs of renewable energy technologies.

Late last year the department of energy released a new draft — the IRP2016 — and public comments on the document closed on March 31.

Even though the draft IRP2016 delays the timelines for nuclear expansion, the plan has been

widely criticised by industry and energy specialists — most notably for using untransparent and flawed costing methodologies for nuclear and other energy technologies.

Previous updates to the IRP2010, which have also been less supportive of nuclear, have never been adopted by Cabinet. This has led to fears that the newest version will be treated similarly and government will push ahead with nuclear procurement based on a policy that is almost a decade old.

A decision to base nuclear procurement on an outdated IRP would be subject to judicial review, according to Gordon Mackay, the energy spokesperson for the Democratic Alliance.

“The plan has been shown to be inaccurate, its demand forecasts are completely off and the demand forecasts are being used as the basis for nuclear acquisition,” said Mackay.

Eskom’s plans to issue an RFP should be placed on hold until a new IRP was finalised, he said.

With the Cabinet reshuffle and the appointment of Mmamoloko Kubayi as energy minister, there was “a huge question mark” over what version of the IRP would be presented to Cabinet, or whether the current version would be presented at all, Mackay said.

Mackay believed that a joint venture mechanism with a nuclear vendor country, despite a poor credit rating, could make it possible for Eskom to pursue nuclear power. He was also doubtful that Russia’s economic conditions would dampen its enthusiasm to facilitate nuclear investment in a country like South Africa.

Russia was recovering from its own recession and had a substantial sovereign wealth fund, he noted.

Eskom considers its options

Eskom spokesperson Khulu Phasiwe said that various scenarios for nuclear funding would be explored and the state- owned company hoped that responses from the request for information would help it to refine its request for proposals (RFP).

As part of the RFP, Eskom intended to obtain information from respondents “on the various funding models for the proposed nuclear reactors”.

This will assist Eskom in ascertaining the commercial viability of a nuclear new build programme that “is affordable for Eskom and the country”, he said.

“The actual cost implication would, however, only be properly ascertained by Eskom during the RFP process,” he said. Eskom would embark on “a competitive bidding process” that is “fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective”.

Russia’s Rosatom ready and waiting

A senior Rosatom official said that Russia’s state atomic energy corporation remained an “interested bidder” for the proposed nuclear programme and would reply to the request for information.

It was premature to comment on financing, because the request for proposals was yet to be published, the official said.

“We therefore do not know any details about the financial model and level of financing the owner operator is considering and expecting.”

Rosatom had noted and respected the government’s decision to move ahead with nuclear power “at scale and pace that the country can afford”.

“Rosatom has a vast amount of experience in working with various project implementation models and various sources of financing,” the official said, which had allowed it to “successfully implement numerous international projects and enabled us to commission a number of units over the past decade”.