People must be reconnected to their natural heritage for conservation to create jobs.

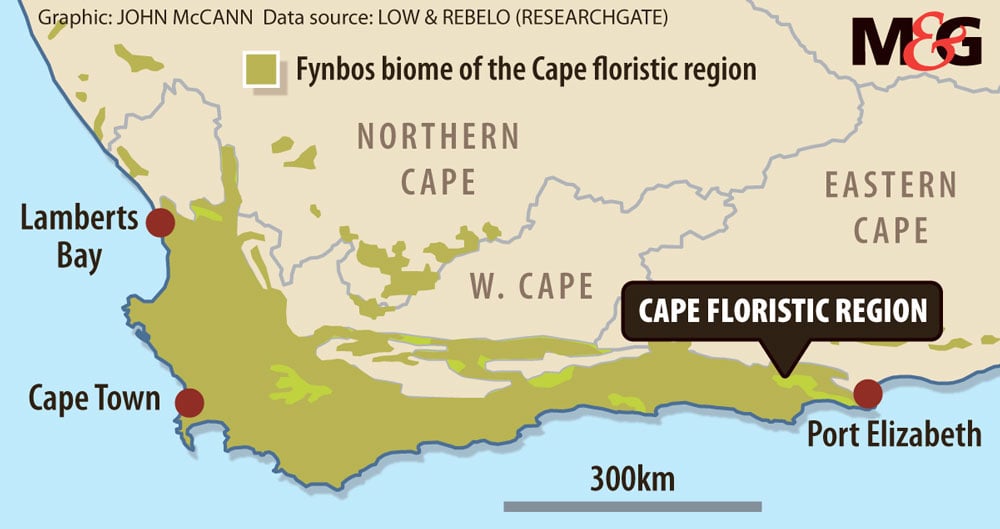

The small strip of land along the Cape coastline is home to one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth: fynbos. Stretching from Port Elizabeth to Clanwilliam, some 8 500 species make up the most dense of the world’s six floral kingdoms. At the heart of this kingdom is the windswept Table Mountain National Park, home to some 1 500 species of fynbos.

Park status has meant the ecosystem – listed as a global biodiversity hotspot – has been kept safe from its principal enemy: the urban sprawl of Cape Town, which has swallowed up other patches of fynbos. It has also allowed officials to combat the invasive Australian acacia, which threatened to outgrow and replace indigenous plants.

But the park and its native fynbos are facing a new threat – a rapidly warming world. This is according to new research from the South African Environmental Observation Network, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The study looked at 54 plots in the park that were cordoned off in 1966, and had experienced fire since then. At that time, the density and type of plant species on each plot were recorded and captured in black and white photographs. A follow-up survey in the 1990s added to these records, before a final survey in 2010.

Put together with weather data, these surveys show that the park is now 1°C hotter than it was nearly 50 years ago. This has meant more frequent droughts.

Fynbos has evolved to survive very specific conditions. Growing mostly underground, many of these plants hide away in the dry summer before sprouting new growth in the Cape’s wet winter. Wildfires, which happen every 10 to 50 years under normal conditions, burn away the vegetation and allow the ecosystem to start afresh.

But increasing temperatures and more frequent droughts have thrown the fynbos survival formula out of the window. The research team found that “the duration of hot, dry, summer weather has increased since the 1960s”.

Random and frequent wildfires – witnessed in the flames that have engulfed the Cape Peninsula in the past few years – keep killing off the new fynbos species that start growing in winter. Across the 54 plots, the researchers found evidence of vegetation density decreasing. Worst affected have been graminoids (grass-like plants) and herb species of fynbos. The researchers predict that the most sensitive species will struggle to survive. But the climate change is so extreme that they do not know exactly which species these will be.

The future is bleak for unique and drought-resistant fynbos species. Along with the increasing heat, droughts and wildfires, projections by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research show that the cold fronts, which bring winter rain to the Cape will retreat further south. This will result in less rainfall in winter. The semi-desert Karoo and dry Kalahari will expand southwards.

Evaluating this future, the researchers said: “This is akin to a game of Russian roulette, and as climate extremes continue to intensify, fewer chambers of the gun are empty.”