Resourceful: Salt evaporation ponds in Walvis Bay.

“Aim for the stars. Even if you miss, you’ll land on the moon,” goes the hackneyed proverb. Namibia is doing neither of those things.

“Namibia does not need to go to the moon or land on distant stars or planets just yet,” writes a disarmingly blunt President Hage Geingob in the introduction of the fifth national development plan, due to be released at the end of May. An advance draft outlines a slow, steady and sober approach to economic development.

Economic Planning Minister Tom Alweendo said in an interview: “I know [South Africans] talk about radical economic transformation, but we’re not talking about that here.”

Instead, Alweendo is hoping that new incentives will attract increased investment in mining and agribusiness, and that this will eventually create jobs. “There was a study that said that 85% to 90% of inputs into the mining sector comes from outside. We think we can reduce that percentage so we can produce those inputs locally. There is already a demand, as long as it is produced efficiently.”

Alweendo, unusually for government ministers, is frank about his government’s failings. “Our economy has been growing, on average, by 4.6% per year, apart from last year. But that economic growth has not been giving the jobs we’re looking for.” He admits that this growth has been based mostly on exporting more of the country’s abundant natural resources and “not because we are creating new opportunities for jobs”.

Around the continent, this is a familiar refrain. Even during the boom years — even as “the hopeless continent” became “Africa rising” — stellar economic growth rarely translated into tangible benefits for people.

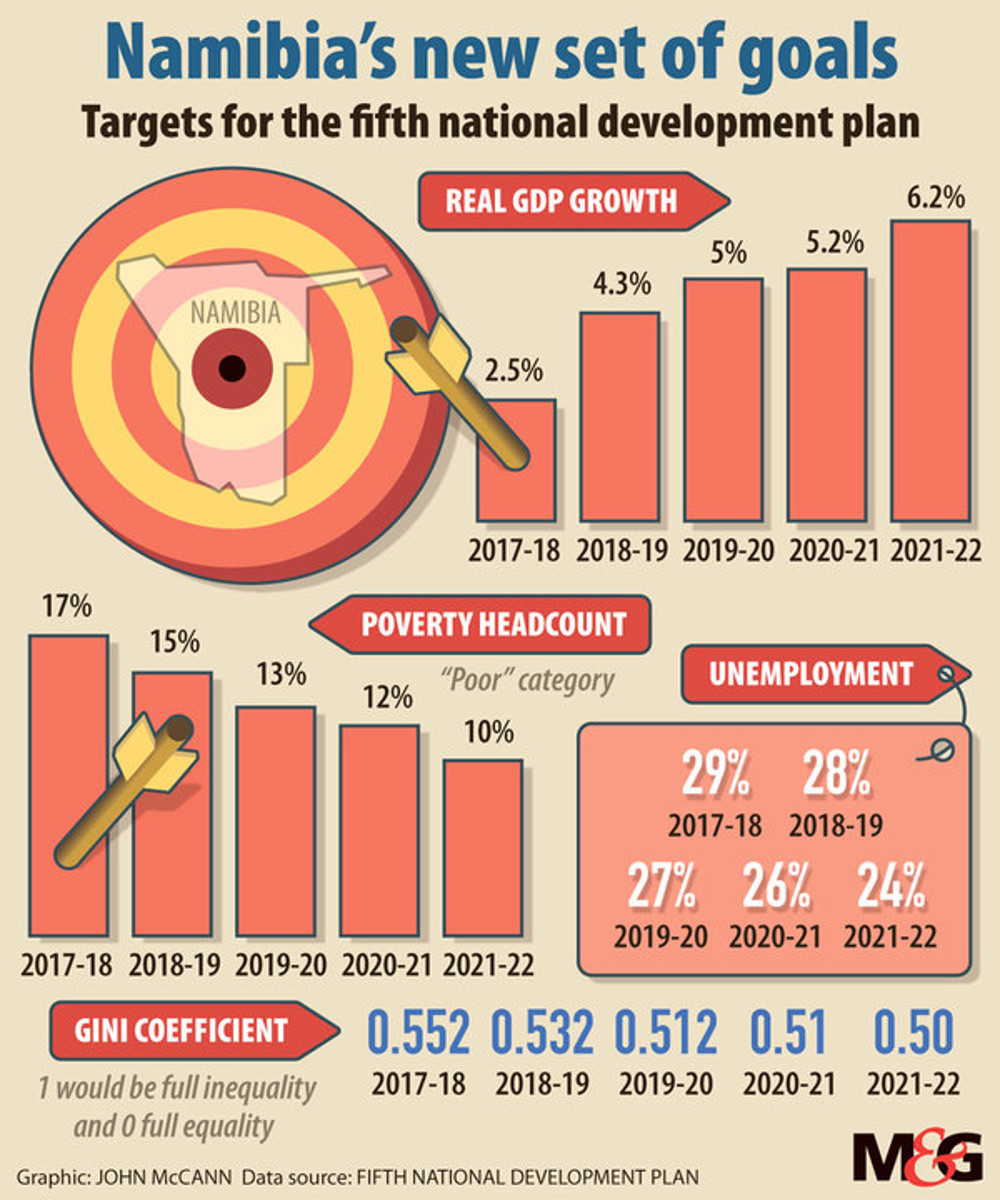

Namibia, despite its resource wealth and political stability, is no exception. With a Gini coefficient (the standardised measure of inequality) of 0.57, it is one of the most unequal societies in the world, and about 18% of its 2.5-million population live below the poverty line. Unemployment is 29%.

It is Alweendo’s job to improve these statistics. “We need to create new industries where we can create new jobs,” he says.

If all goes according to the plan, by 2021-2022, Namibia will be growing its gross domestic product by more than 6% a year, unemployment will be down to 24%, and poverty will have decreased to 10%.

The country will be less unequal, but not that much less: the plan envisages improving the Gini coefficient to 0.5. This would, by today’s rankings, still put it among the top 20 most unequal countries.

The pace of the envisaged changes is slow. One of the plan’s housing goals is to upgrade informal settlements at a rate of just two a year.

Alweendo is all too aware that the success or failure of the plan is not entirely in Namibia’s hands. As a relatively minor player in the region, its fortunes are inextricably linked to those of its much larger neighbour, South Africa.

“We are a very small economy sandwiched between two large economies, Angola and South Africa. But because of our history, we still import most of our goods from South Africa. When things don’t go well there, we are worried … we’re hoping that those bigger than us get it right, because our future prosperity depends on it.”

Not everyone agrees with Alweendo’s cautious approach. Last month, The Economist reported that a draft Bill, the New Equitable Economic Empowerment Framework, would introduce “racial quotas”, requiring companies to be at least 25% owned by previously disadvantaged persons.

This idea was a response, apparently, to pressure from within the ruling party to hasten the speed of economic change, although critics suggested it would only benefit black Namibians who are already wealthy and influential.

The government has dismissed The Economist’s report and insists that the provisions in the draft Bill are still being debated.

But the pressure for a more radical strategy is real. Yet, with all its modest, relatively achievable goals, that is one demand Namibia’s new national development plan is not planning to fulfil.