NEWS ANALYSIS

Funding for parastatals is shrinking as concerns over their governance and financial performance begin to hit home amid credit rating downgrades.

The treasury said this week it is concerned about the recent poor result of parastatal bond auctions, “which may be an indication of some risk aversion or liquidity drying up in the market”.

The beleaguered power utility Eskom has not issued bonds on public auction for more than a year, according to people in the industry, and others such as the South African National Roads Agency (Sanral) have postponed auctions.

Logistics parastatal Transnet recently battled to raise its targeted amounts. In April and early May, during three consecutive auctions, Transnet garnered only R45-million, far less than the R100-million it raised at each auction before President Jacob Zuma reshuffled the Cabinet, according to Nazmeera Moola, the co-head of fixed income at Investec Asset Management.

This week’s revelations by investigative journalism unit amaBhungane that the Gupta family and their associates allegedly received kickbacks of some R5.3-billion from Transnet’s locomotives contract are unlikely to reassure worried investors.

The “governance gaps” at most state-owned entities (SOEs) were a serious concern and something that had to be sorted out urgently, the treasury’s spokesperson, Yolisa Tyantsi, said in response to questions from the Mail & Guardian.

“Without any doubt, these problems will invariably filter to funding pressures,” she said.

It was for this reason that the treasury was actively involved in the reform of state-owned companies, which is being led by Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, she said.

There is growing concern that the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), which invests on behalf of the Government Employees Pension Fund, has been called on to pick up the tab because of the private sector balking at taking on parastatal debt. The government denies this.

The PIC manages about R1.8‑trillion in assets on behalf of public servants.

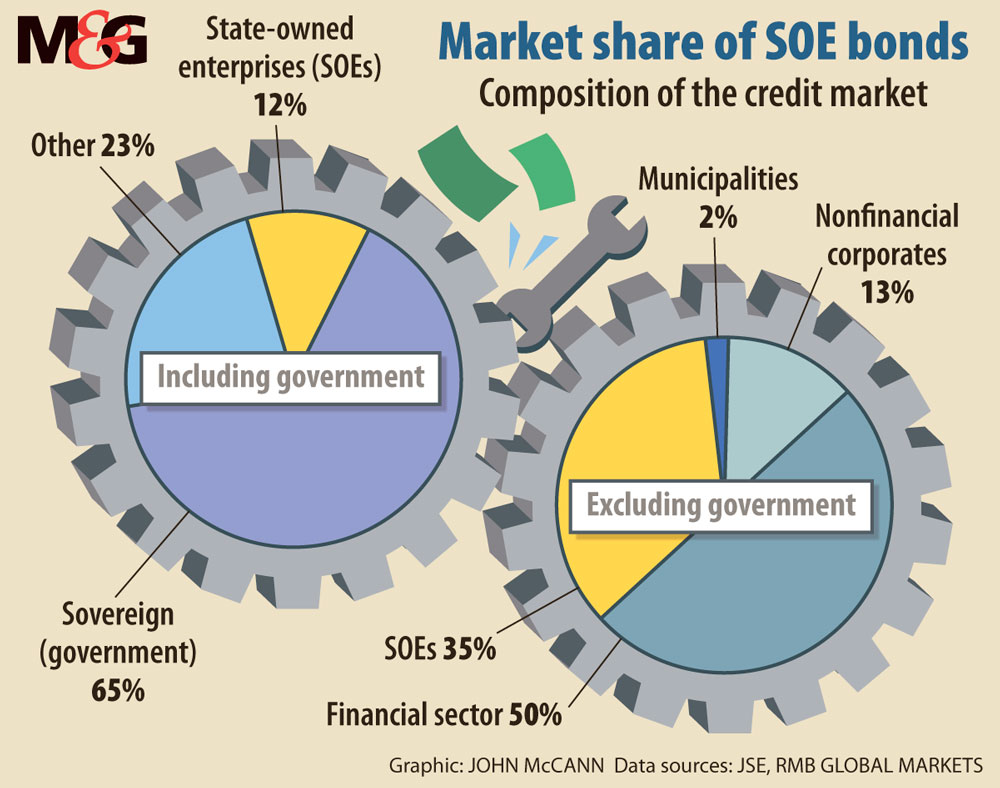

At the end of March, parastatals made up 12%, or R289‑billion, of South Africa’s credit market, which is currently at about R2.4‑trillion, according to data from the JSE and research by RMB Global Markets. This figure includes commercial paper-debt instruments that mature in less than a year.

Eskom, Transnet and Sanral are the largest state-owned enterprise bond issuers, and Eskom and Transnet are both involved in major investment programmes that depend on their ability to raise money in capital markets at affordable rates.

“Over the past 18 months, there have been increasing concerns about the corporate governance at SOEs, in addition to long-standing concerns about the financial performance of some of the SOEs,” a credit analyst who did not want to named said.

“As perceived risk increases, investors need to be compensated for the risk they take; therefore, returns have to increase. If the return on investment does not compensate for the risk, it will not be prudent to undertake such investments.”

According to an analysis by Moneyweb, the PIC now owns more than 56% of Eskom bonds, more than 64% of Transnet bonds and 48% of Sanral bonds.

But the treasury said it was not concerned about the PIC’s large holdings of parastatal debt.

“They [SOEs] are the second-largest nongovernment bond issuers on the JSE, and PIC is the largest money manager,” Tyantsi said.

The government did not interfere with PIC investments processes or attempt to influence the PIC to fund SOEs, she said.

The government and parastatals tend to issue long-dated bonds and are the largest issuers of inflation-linked bonds. These are preferred by pension fund managers and it “was not a surprise” that the PIC would be the largest holder of such instruments, she said.

Moola said international investors traditionally have not played a major role in South Africa’s corporate and state-owned enterprise bond market.

Following the Cabinet reshuffle, local investors have been increasingly concerned about governance risks and have steadily become net sellers of these bonds, she said.

“It’s not surprising that state-owned companies have been struggling to issue. Foreigners were never part of that market,” she said.

Parastatals had been struggling to issue debt even in an environment in which a recent increase in the uptake of government bonds by international investors had helped to keep yields relatively low, she added.

Tyantsi said the issuance of bonds through private placements had been taking place for some time now and Eskom had opted for this approach in an effort to avoid “unfavourable pricing in the market while ensuring success in its issuances”.

It had introduced new debt instruments, which were not government guaranteed, suggesting that it “was making every effort to reduce its reliance on guarantees”.

But unguaranteed bonds are pricier for parastatals to issue. According to a recent debt management report, during the 2015-2016 financial year, the average spread for guaranteed bonds with a five-year tenure was 65 basis points above the government benchmark, and bonds with 10- and 15-year tenures had an average spread of 73 basis points and 101 basis points, respectively.

The average bond spreads for state-owned enterprises’ unguaranteed five-year, 10-year and 15-year tenure bonds were higher at 131 basis points, 147 basis points and 143 basis points, respectively.

Eskom and the PIC did not respond to requests for comment.

Transnet said it did not believe that the downgrade and the impact of liquidity in the domestic bonds market would have a major impact on its financial position and operations.

In the past three months, it had received bids of up to R400-million, but it had to reject bids that were above its benchmark pricing range.

It added that there was less demand for longer-dated fixed bonds that Transnet is auctioning. The company believed these were better than short-dated bonds, which would create refinancing risk.

It met ratings agencies’ liquidity requirements and retained solid relationships with financial institutions, which enabled it to secure more than R16-billion in unused short-term credit facilities, which were available within 24 hours.

In addition, the company said it could tap into liquidity of R114‑billion, including R32‑billion in committed facilities to meet its funding commitments.