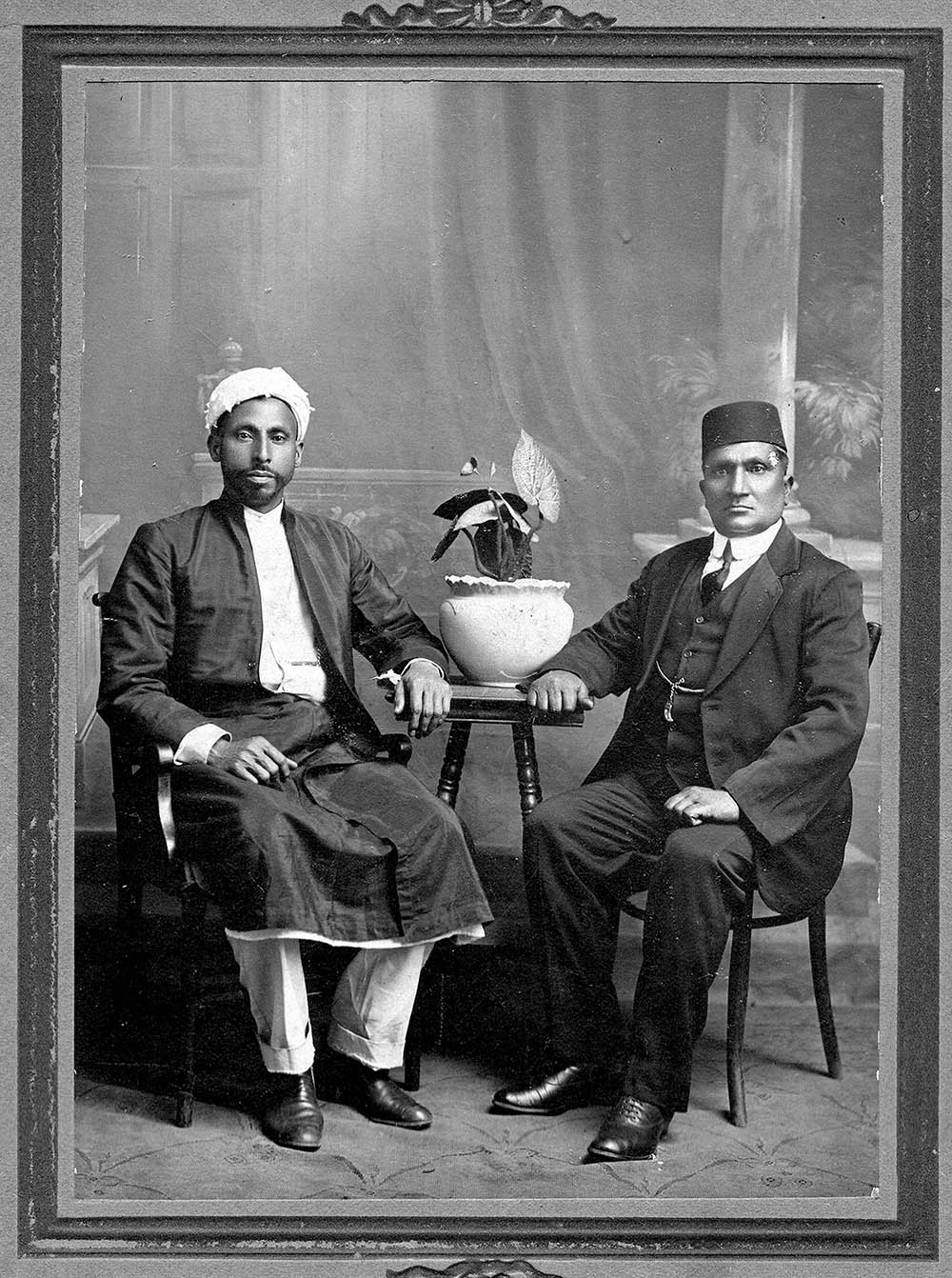

Roy and Ama

When I first meet up with the Naidoo-Pillay family at the Apartheid Museum in southern Johannesburg, panels are still being installed in a circular exhibition room to the South of the building.

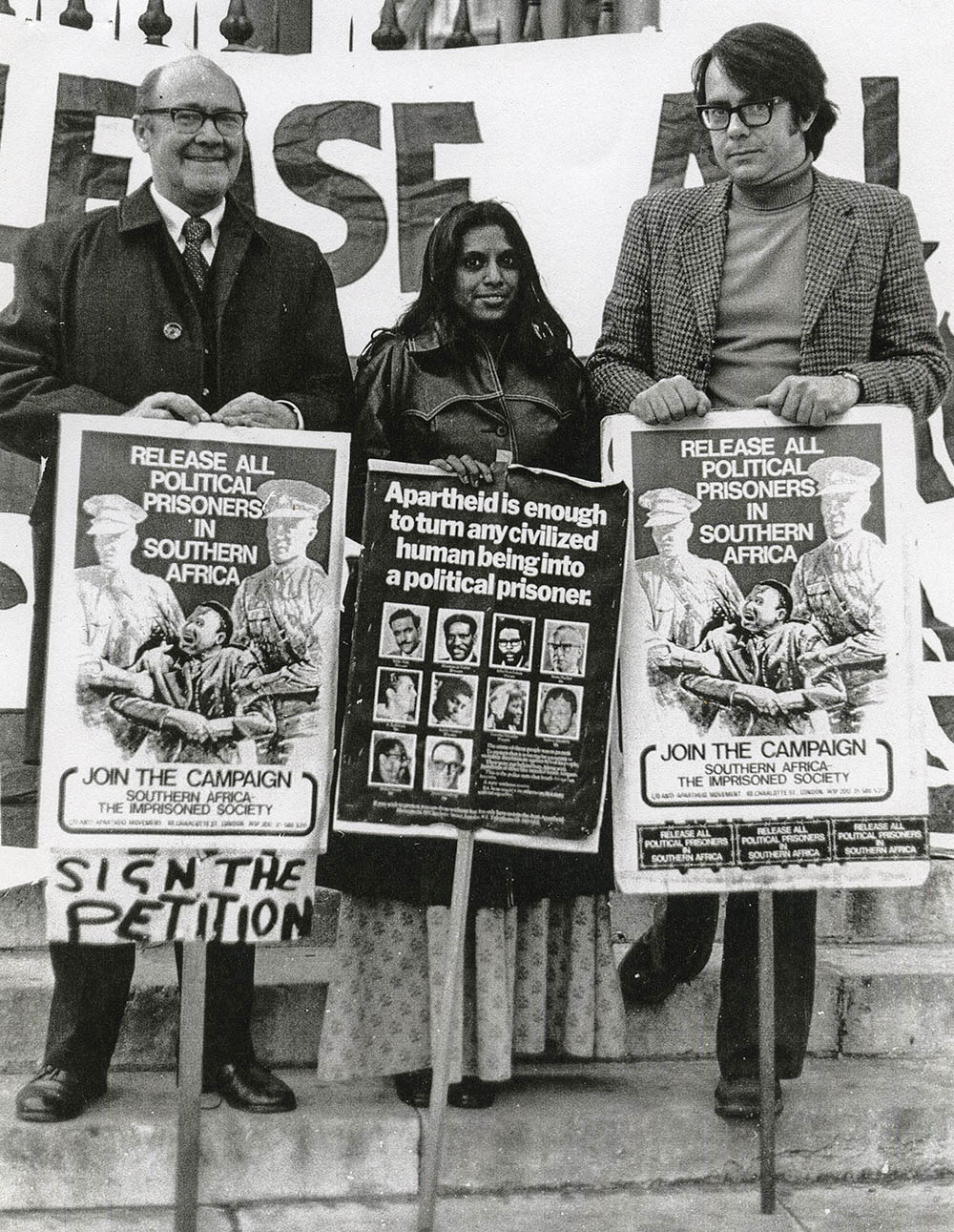

Amid the drilling by workmen readying the room for the launch of the exhibition Resistance in their Blood, subtitled The Naidoo-Pillay Family: Pacifists, Protestors, Prisoners, Patriots, Ramnie Dinat, the formerly exiled daughter of Narainsamy “Roy” Naidoo and his wife Manonmoney “Ama” Naidoo, tries to orientate me.

It is a family whose history of struggle stretches back to the beginnings of Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha philosophy of passive resistance, through the armed struggle to the United Democratic Front and then South Africa’s democratic dispensation, she says.

As we walk from the exhibition space to a boardroom near the rear entrance of the museum, we walk past snatches of a school choir singing Nkosi sikelel’ iAfrika and a snippet of a Nelson Mandela video, all part of the museum’s permanent exhibition. “When you say, ‘I am a man,’ ” Mandela says to an invisible interviewer, “they wanted to see it themselves. So your body language …” As his voice trails off, I think about the typically masculine ways in which the anti-apartheid struggle has been framed. Most histories present the struggle largely as the domain of wise old men communing with young lads eager to pick up arms.

The Naidoo-Pillay family story also begins with that of a patriarch — Thambi Naidoo — but is counterbalanced by the involvement of a large number of women as subsequent generations assumed the mantle.

As Dinat takes a seat in the quiet boardroom, she is joined by her siblings Murthie, Shantie and Prema, as well as his wife Kamala.

“Rockey Street, Doornfontein, is where we [our generation of siblings] were all born and lived for 40 years,” says Dinat, of the famous People’s House.

People who came into contact with the family remember the house as important in maintaining morale during and after the Treason and Rivonia trials. “My father Bram [Fischer] was close to Roy,” says Ilse Wilson.

“That house in Rockey Street was where people of all colours met. People would go there to be fed, looked after or just meet other people. Roy died young, he had a bad heart, but Ama [Naidoo] kept this extraordinary house going. The important thing about this family was that they kept their beliefs.”

Wilson, who played an important galvanising role towards this exhibition’s fulfilment, says, even though the women in this family were not always visible, the role they played in the struggle was crucial.

“Ama was not always upfront, but she was active in the women’s federation. In the [1956] women’s march [on the Union Buildings], Ama went but so did Ramnie, who must have been quite young at the time.”

Beyond its political importance, Wilson says, the house was an important site of social activity. “If you were going to a party, you could stop over to get dressed in a sari by Ama and Shantie,” says Wilson.

Shantie received one of her banning orders while attending the trial of Fischer, who, in 1966, was accused of sabotage and the contravention of the Suppression of Communism Act.

This family story starts with Thambi Naidoo, who was born in Mauritius in 1875. Alongside his brother and sister, Naidoo travels to South Africa, first to Kimberley before moving to a Johannesburg in the throes of a gold rush.

A trader, Naidoo hawked produce and grew his business to encompass cartage and wholesaling. By the age of 19, Naidoo was politically active, leading a delegation to the city’s municipal council and another one to Paul Kruger, then president of the Transvaal Republic in 1895.

Trade restrictions and taxes imposed on Indians were making economic life unbearable and some of the earliest campaigns were mounted to address these issues.

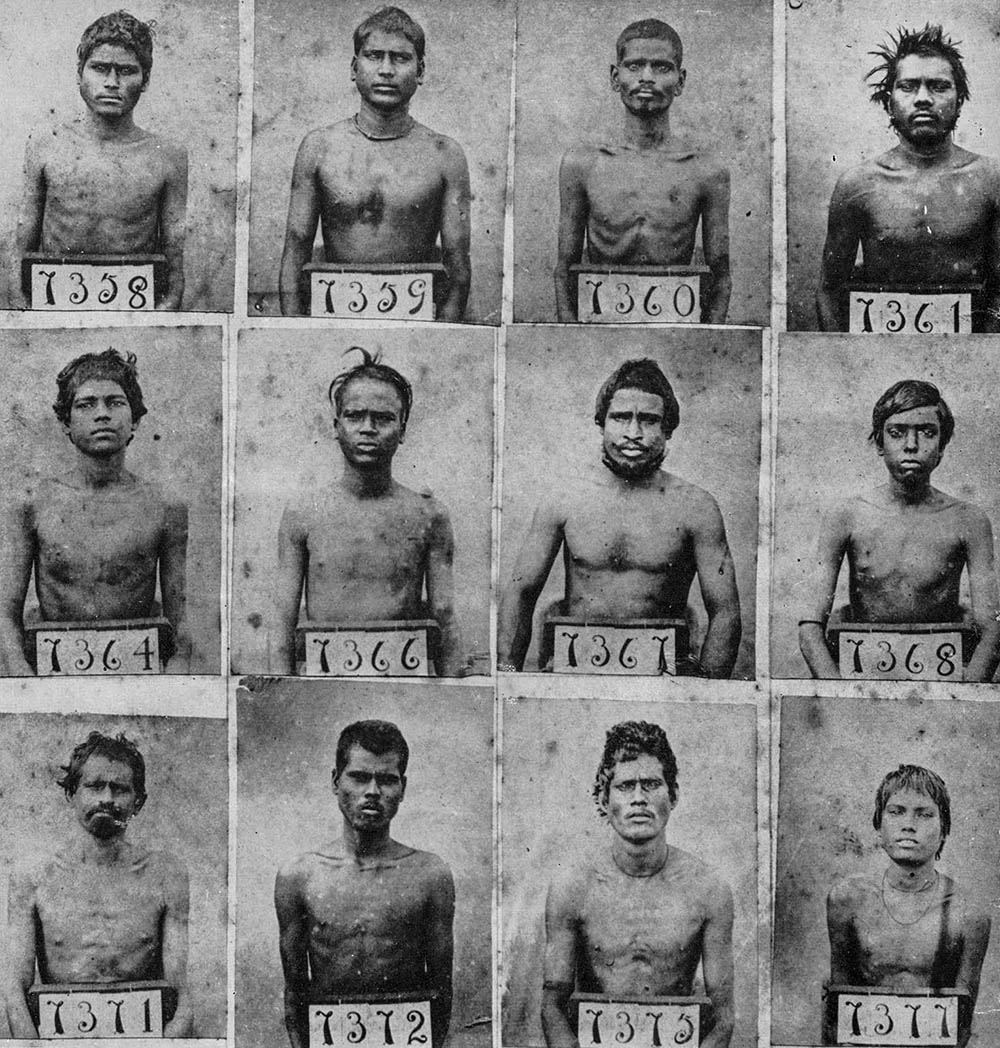

Contextualising the conditions, ES Reddy writes: “In 1906, when the provincial government of the Transvaal passed an ordinance for the registration of Indians to force them to carry certificates to be shown on demand by the police, Gandhi decided that there was no choice except to defy the law.

“He led the resistance of Indians in the Transvaal in which well over 2 000 people, out of a population of about 10 000 went to prison. The struggle was extended to the whole of South Africa in 1913.”

By 1907, aged 32, Thambi Naidoo became a member of the Transvaal British Indian Association, an organisation in which Gandhi served as secretary. Naidoo, a charismatic organiser who was fluent in many languages, was first arrested in 1910 as a satyagrahi and, after that, on more than a dozen occasions.

Thambi’s wife, Veeramal, was arrested during the 1913 passive resistance campaign and went to prison while pregnant, taking with her her infant daughter Sashamal and giving birth to her son, Meetlan, a day after being released.

By the 1940s, when the Natal and Transvaal Indian Congresses were organising passive resistance campaigns against the Ghetto Act, Thambi’s son, Roy, and his wife, Ama, were earning their stripes through involvement in the struggles of the day.

In 1954, Ama was elected as an executive of the Federation of South African Women and the following year she took her children to the Congress of the People convention.

Ama and Roy’s children, Murthie, Indres, Prema, Shantie and Ramnie joined the ANC, with Indres joining the ranks of uMkhonto weSizwe soon after it was established. Indres was captured alongside his MK commander Reggie Vandayar and Shirish Nanabhai after blowing up a railway station shed and attempting to dynamite a signal relay case. Shot, captured, operated on to remove the bullet and then taken bleeding to Rockey Street for a raid, Indres was eventually sentenced to 10 years on Robben Island.

Although not all family members shared this view, Indres took up arms in the struggle was for the purpose of achieving peace.

For such a storied family, following their history takes a fair amount of study. Resistance in their Blood functions as a conveniently compartmentalised beginners’ course.

Curated by Apartheid Museum’s Emilia Potenza, the exhibition is divided according to important family sites — such as Tolstoy Farm, the HQ of the satyagraha campaign and where Gandhi started a community; Walmington Fold, London, where some family members lived in exile; Rockey Street and Marabastad, Pretoria, — struggle involvement through the generations (including exile and return) and the shift from passive resistance to the armed struggle.

Looking at the panels augmented with archival photographs, one begins to get the sense of how the struggle was, beyond a physical journey, also a journey of reckoning with philosophies and ideas.

There are also artefacts — such as Thambi’s daughter Thailema Pillay’s milk canister, used to feed trialists during the Treason Trial — which is a timeless reminder that ultimately, the struggle was not only about brawn but also about service.

Resistance in their Blood runs until the end of August.