After a postponement of the highly anticipated general assembly

The National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) funded 466 000 students this year. But 46 000 others who met the qualifying criteria have been left out in the cold, even after the government put an additional R8-billion into the pot as a result of pressure from the #FeesMustFall student movement.

While the Presidential Fees Commission mulls over whether higher education should be free for all and, if so, how it would be funded, there are already at least two seemingly achievable models on the table.

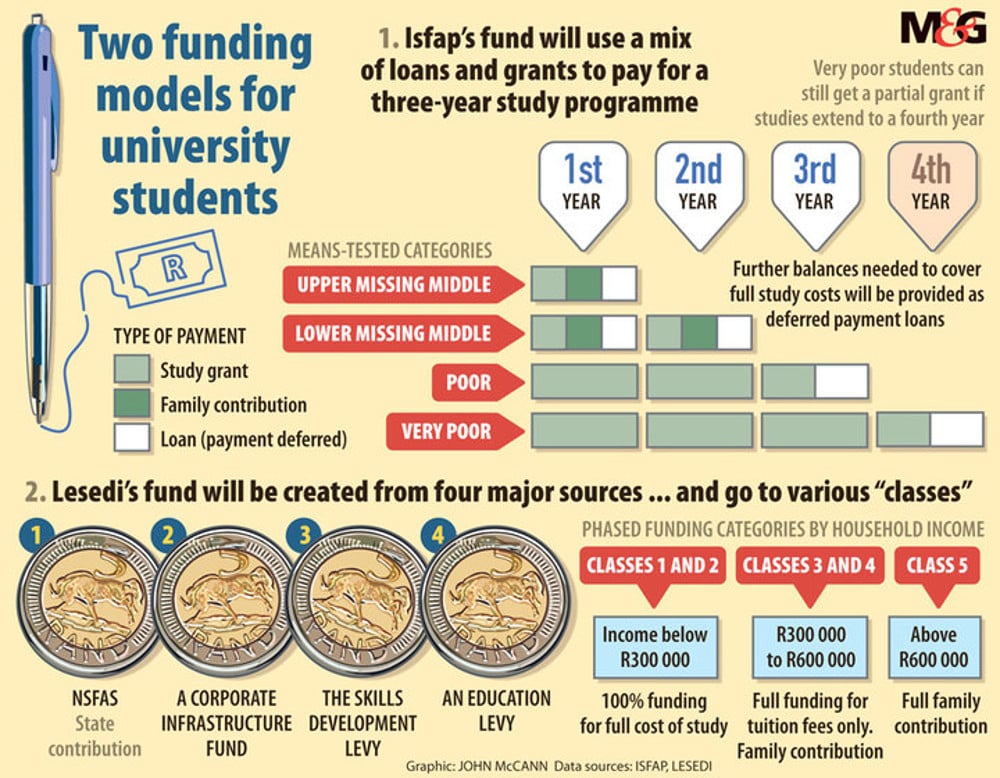

One funds the poor and so-called missing middle students through both grants and loans. The other proposes free higher education for all. Both would require an enormous amount of additional money — estimated to be as much as R27-billion a year respectively — to fill the funding gap. The current NSFAS budget is R10-billion for the year.

The Ikusasa Student Financial Aid Programme (Isfap)

A ministerial task team headed by NSFAS’s chairperson, Sizwe Nxasana, has produced a blueprint to fund poor and the missing-middle students through the Ikusasa Student Financial Aid Programme.

Its aims are fourfold: to give the majority of students from poor backgrounds free higher education; to reduce the high dropout rates of poor and working-class students; to improve the employability of the funded graduates; and to improve the skills profile of the country.

Nxasana said the model would be based on a partnership between the government, NSFAS and the private sector.

Despite growing demand, government subsidies contribute proportionately less to the funding of higher education institutions each year.

Currently, NSFAS gives students study loans, up to 40% of which can converted into a grant, which does not have to be repaid depending on academic performance. The loan amount is capped at R76 000 a year per student. Any other costs must be covered by the student. The main qualifying criteria is that the student must come from a household that earns less than R122 000 a year.

The task team’s model will assist all students from households earning less than R600 000 a year. It breaks down these students into different groups, based on household income, and proposes the use of both grants and loans.

The “very poor” group will be given grants for the first three-and-half years of study. The balance of the fourth year will be covered by a loan.

The “poor” group will be given grants for the first two years of study and the cost of the third year will be split between a grant and a loan.

The “lower missing-middle” group will be given a grant to cover the cost of study for the first year only. “Upper missing-middle” students will be given a grant for half of the first year.

The families of lower and upper missing-middle students will be expected to contribute to their costs, according to their income.

All students will be able to get loans for the completion of their studies.

This model proposes a higher allocation of funds to those who will acquire scare skills.

Nxasana said a key component of this model will be comprehensive support. It will include academic, social, medical and psychosocial support, life skills training and mentoring.

The cost of the model will be about R45-billion in the 2018-2019 year and various sources of funding will have to be tapped, he said.

The task team describes the loans as an “income contingent deferred payment facility” — a graduate will only begin repaying this when they begin earning. The repayments will be collected by the South African Revenue Service (Sars) and the task team has proposed a change to the Tax Administration Act to allow this.

Black employment empowerment legislation could be another funding option, Nxasana said. It could offer incentives to companies that offer internships or workplace based programmes to graduates. In the 2018-2019 year, this could raise R10-billion.

Social impact bonds, a pay-for-success model, could also help to raise funds. For example, private funders could contribute to the costs of support for students and the government or an industry with vested interests in their skills could pay the funders back based on the success rate of the initiative.

The Ikusasa model is being piloted at seven universities. But this model falls short of student demands for universally free higher education.

The Lesedi Education Endowment Fund

In September last year, the government announced that university fee increases would be limited to 8% in 2017, which resulted in widespread student protests.

At a mass meeting at the University of the Witwatersrand, students resolved to draw up their own funding model and enlisted the help of an accountant and academic, Khaya Sithole.

“They said to me there are two non-negotiables: it must be free for everyone and we refuse to pay for it,” he said.

The student-mandated model, created with Sithole’s help, and dubbed the Lesedi Education Endowment Fund, proposes sustainable ways to fund higher education and rejects the idea of loans entirely.

Sithole puts the potential funding gap at R27-billion a year.

The model proposes four funding sources: The NSFAS, the skills levy, a new education levy and a corporate infrastructure fund.

First, Sithole said, the government must provide half the income required by higher education institutions. In the year 2000, government funding contributed almost 50% to the income of higher education income but it has dropped and was only 38% in 2014. But, since 2000, the total cost of study has increased by 72% and university enrolments have grown by 96%.

Sars currently deducts an existing skills development levy. It is 1% of a company’s salary bill and is channelled to the sector education and training authorities (Setas) and the Skills Development Fund to pay for training. Of that, 40% goes back into the university system.

But Sithole said some Setas are totally dysfunctional and there is leakage. “Last year, the Setas collected R18-billion, [and] 40% of that is R7-billion that could have gone straight to NSFAS,” he said. “It’s a solution that doesn’t require anything be done differently. Everyone is already paying it.”

Alternatively, the levy could be increased to 1.5%, with the difference being used to fund free higher education.

The Lesedi model also proposes an education levy of between 1% and 2%, which, like the skills levy, could be deducted from employee income. This would be the students’ contribution into the system, Sithole said.

“University students, rich or poor, all benefit from a subsidised system, but it only seeks to recover funds from the poorest students who tend to have the worst graduation rates,” he said. “If everyone has benefited from subsidised education, then an education levy should be collected from everyone who exits the system.”

Lastly a private-sector corporate fund could pay for much-needed infrastructure upfront with the government granting them tax rebates in return. The funds would go towards clearing historical debts and insourcing staff at universities and colleges — a key demand of the #FeesMustFall movement.

The funding of students would be phased in, with the costs of those coming from households earning less than R300 000 a year being paid in full. The tuition costs of those from households earning between R300 000 and R600 000 a year would be paid, with their families paying their other costs.

“We are saying, start off with the poor — the amount of poor people who actually get to university is not that great a number — and, once the system is self-sustaining, let us expand the net,” Sithole said.

Ultimately, the final model will be decided by the government based on the outcome of the Ikusasa pilot and feasibility study, public suggestions and the recommendations of the presidential commission.