(Oupa Nkosi)

The previous two #investmentMatters articles gave an insight into retirement: how much you need to save, and the ins and outs of living annuities.

Now we’re moving on to Retirement 2.0. What are some other ways to invest your nest egg?

“For the current group of millennials … who are moving on to a new mind-set of flexibility and choice, the question is: In which product should they consider when saving for retirement?” said Karen Wentzel, the head of annuities at Sanlam Employee Benefits. “Is the traditional pension and provident fund arrangement still appropriate? Is there a better way to save?”

Here is an example to illustrate the risks and possible returns of two other investment options. We’re using a lump sum of R5-million. We’ll look at putting our R5-million into a fixed deposit account with a reputable bank. Then we’ll look at investing all that money in property.

FIXED DEPOSITS

Business confidence is at a low and investors would be forgiven for wanting to take a conservative approach.

Several banks offer fairly attractive returns on fixed deposits, with interest of between 6.5% and 10.5%, depending on the amount of money and the length of time it is invested. Seniors (over the age of 55) qualify for more favourable interest rates.

But fixed deposits are for a stipulated time and, if you wish to withdraw the money before that, the cash is then subject to penalties. For example, Standard Bank offers annual interest of 10.15% to investors who put aside R100 000 for five years and don’t touch it. Those who do draw it before maturity only qualify for 8.7%.

The more flexibility you seek, the less attractive the returns. For example, FNB offers 9.15% interest to seniors who invest R5-million or more for five years. But the interest rate is decreased to 6.55% if you to draw the cash after a month.

What you get out

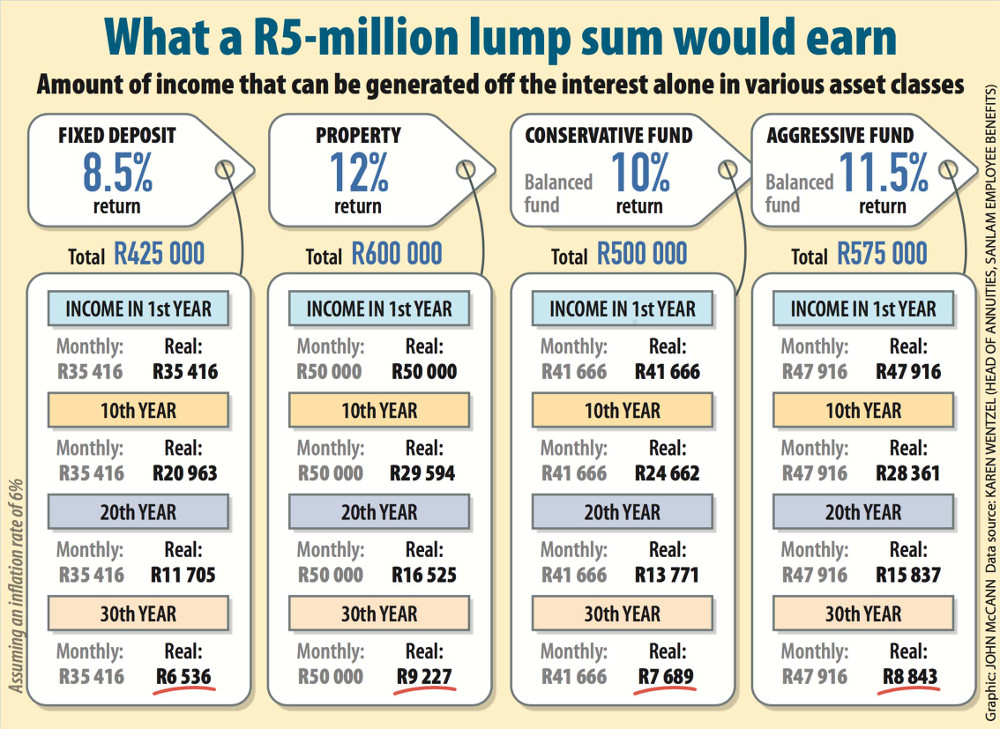

Based on a return of 8.5%, the interest would earn you a monthly income of R35 417 in year one, said Wentzel. But, in real terms, that amount would be decreased by inflation every year. Assuming inflation of 6%, by year 10 the monthly interest of your R5-million would be worth R20 963. By year 20, the value would have decreased to R11 705. By year 30, you would only be earning about R6 536.

Ups and downs

The upsides: your risk is low and your assets are liquid. The downsides: you’re likely to earn lower interest rates than more risky investments. You need to weigh up having easy access to your cash or better returns.

PROPERTY

Let’s posit you took R5-million and bought residential apartments, which you then rented out to generate an income for your retirement.

Richard and Debbie Angus are property investors who have done that. They own and rent out several flats, and their aim is to have all the properties paid up by the time they retire in roughly 20 years’ time.

The return on such investments vary according to the property, the area, rental incomes, maintenance costs and interest rates. But the real differentiator in what kind of returns you will receive comes in how you finance the bond, said Richard.

He cites two scenarios, both of which take into account the bond repayment, levies, rates, collection costs and maintenance, and the costs of a rental agent, and assume a two-bedroom residential rental unit at a cost of R820 000.

In the first scenario, the property is unbonded (paid for upfront). Over 20 years, assuming that interest rates remain unchanged and that the

rentals and property prices increase at 9.86% — the same rate as they have over the past 20 years — an investor selling the property in the 21st year would make a real return of 8.14%.

In the second scenario, the same property under the same set of circumstances but bonded at R810 000 would yield a real return of 17.17%.

The reason there is a higher return on the bonded property is you can buy many more properties (on credit) than you could buy if you owned them all outright. In the first scenario you would need all the capital upfront to pay for the house; in the second scenario you need only a small portion of the capital, and can acquire more properties while you pay back the debt.

“You will notice that the property owner is paying into the bond until about year eight, before break-even is achieved,” Richard said. “By using the bond, the effect on the return is significantly higher at 17.17% real return. Effectively it’s a return on the R10 000 invested upfront.”

The Anguses have adopted this approach. They have bought “several smaller units that we funded initially on the premise that this would be our retirement fund in 20 years’ time”, he said.

His calculations show his property portfolio will outperform the local equities market, which showed an average real return of 11.19% between 1996 and 2015, according to a study conducted by PSG Asset Management.

“I think this rate of return is pretty decent,” Richard said. “First, property is less volatile than equities — the pricing is more predictable and is based on supply and demand, rather than perception. Second, property by its nature is a long-term hold, so a 20-year investment horizon works. Equity is an active asset class and needs to be constantly re-evaluated.”

What you get out

A general rule of thumb is to assume a 6% capital gain on the value of your property and 6% return from rental income.

Wentzel provided calculations based on R5-million and working on 12% interest with inflation of 6%.

You would take home R50 000 a month on the interest alone in the first year. By year 10, that amount adjusted for inflation would have decreased to R29 594; by year 20, it would be R16 525, and by year 30 it would be R9 227.

Ups and downs

You can expect the returns on property to outstrip fixed deposits and possibly even outstrip (or keep pace with) equities. The downsides: your assets are not liquid.

“It can take you six to nine months to exit a property — not great if you need to cash out in a hurry, ” Richard said.

Second, your individual tax position could affect returns. “Additional taxes imposed at any time in the 30-year cycle can have a material impact on the returns,” he said. “For example, the wealth tax being suggested on properties, the changes in the way rates and taxes were handled, and so forth.”

Third, a high-gearing portfolio such as the Anguses’ is “extremely risky”, he said.

“A small change in interest rates has a massive impact on the entire portfolio and can literally result in one going insolvent. So, whilst equities face volatility of the markets,

a high-gearing scenario has the risk of increasing interest rates,” he added.

Leonard Kruger, the manager of the Allan Gray Stable Portfolio, said would-be retirees should use their risk capacity rather than their risk appetite to guide their choice of asset.

Your risk appetite is the risk level that appeals to your personality but “your risk capacity is the risk you can afford to take”, Kruger said.

If you have a surplus of cash saved up, you can afford a low-risk option. But if you need your cash to grow aggressively during retirement, a riskier option often becomes prudent.