Utopia unmasked: In Kigali

LONG READ

You probably don’t know much about Rwanda. Gorillas. Genocide. Don Cheadle. Maybe you’ve heard of Paul Kagame, the president. Maybe you’ve come across the phrase “Africa’s Singapore”, although what exactly that looks like, or what it means, is a mystery.

You need to know more about Rwanda.

In the grand scheme of African development, Rwanda is an experiment, a trial run, a test case for a new type of society. And the experiment is about to be repeated in a country near you.

Rwanda is your future, whether you like it or not.

At least, that’s the plan. In Africa’s air-conditioned corridors of power – in the boardrooms of its banks, in closed-door Cabinet meetings, in donor discussions and interminable governance conferences – it is repeated like a mantra: “The Rwanda model. The Rwanda model. The Rwanda model.”

After decades of searching, Africa’s leaders think that they have found a homegrown, Afrocentric development plan that works, and they are vigorously spreading the doctrine.

The praise-singing cuts across sectors and geography. Here’s Benedict Oramah, president of the African Export-Import Bank, shortly before handing Rwanda half a billion dollars in development financing: “This is a country that was all but written off some two decades ago. But just like the phoenix that died and arose from its ashes, it emerges to become the shiniest star on the continent. The shiniest in terms of governance, in terms of the can-do spirit, doing those things that nobody ever thought was possible.”

The 1994 genocide is observed at a Meeting of Remembering (bottom right), but critics say the tragedy is used by the ruling elite to quell criticism. (Phil Moore/AFP)

Here’s the Africa boss at the World Health Organisation (WHO), Dr Matshidiso Moeti, explaining why she chose Kigali for this year’s first ever Africa Health Forum. “I want to recognise [Rwanda’s] remarkable leadership – its creativity, tenacity and resolve – which have delivered significant progress in advancing health and development for the benefit of all your people. Your achievements in such a short space of time are truly remarkable.”

And here is Olusegun Obasanjo, the former Nigerian president turned elder statesman-in-chief. “Rwanda has made difficult trade-offs. But as an African leader, I tell you that I would make the same trade-offs.”

Kagame – slender, bookish-looking – is so popular among his fellow leaders that the African Union has chosen the Rwandan president to lead the commission to reform the struggling continental institution.

It’s his job to make the African Union more efficient and effective and, in the process, implement some of his ideas on a much grander scale. He has also been elected to chair the African Union at this month’s summit in Addis Ababa: a largely ceremonial role, but one that serves as yet another glowing endorsement from his peers.

Africa’s big men love Rwanda. So does the big money, and the world’s big institutions. But what exactly is the Rwandan model? And why should the rest of us be worried?

The shining city on the hills

Kigali is immaculate, and quite unlike any other African capital. It is a city of well-tended verges, neat houses and quiet roads. Houses cling to the precipitous slopes and the valleys below are reserved for parks, urban farms and a golf course. The views are dramatic: all you see, in every direction, are pyramids of dense habitation floating on a lush green sea.

This is Kagame’s showcase, and it’s hard not to be impressed. For human resources purposes, the United Nations ranks Kigali alongside New York in terms of ease of living. The restaurants are great, there are several world-class hotels and you can walk wherever you want at any time of day or night without fear of mugging or assault.

‘There was nothing like this 23 years ago,” says Magnifique, my tour guide, as he points out yet another high-end housing development. “One day, everyone will have a house with two storeys.” Then he points out the single-storey, low-income tenements next door. “These people know they have to go soon. They must build a new house or go somewhere they can afford.”

For Magnifique, it’s not a question of if, but when. “Come back next year, or in two years at most, and you will see the new houses.”

Kigali. (Peter Moore/AFP)

I don’t doubt him for a second. This is why policymakers love Rwanda. Every country has grand development plans. Every country makes promises. But Rwanda, almost uniquely in Africa, routinely delivers on its promises. It gets things done.

Take as an example improvements in healthcare, which is a cornerstone of Rwanda’s development model. The improvements for the country’s 11.6‑million-strong population are almost unbelievable. According to health ministry statistics, life expectancy is up to 64.5 years from just 49 in 2000. Child mortality is down more than two-thirds. Maternal mortality is down nearly 80%. HIV/Aids prevalence is down to 3% from 13%. There is now one doctor for every 10 555 people, compared to one doctor for every 66 000 people in 2000.

Dr Olushayo Olu, the WHO’s Rwanda director, says the extraordinary statistics are supported by the WHO’s own research and talks me through how Rwanda did it. “The main ingredient is visionary leadership. It’s about having a target, saying we want to be there in the future and understanding obstacles in the way.”

Key to getting there is accountability and a performance-based system where each layer of society must answer to the layer above. “Mayors and top officials sign performance agreements with the president himself,” said Olu.

Accountability is an art form perfected by the Rwandan government. Provinces are divided into districts, which are then divided into sectors, then cells and finally villages.

The village, or umudugudu, is the primary organising block of Rwandan society, and it is key to Kagame’s control. Every Rwandan belongs to a village, even Kagame – the presidency is called Urugwiro Village. There are more than 14 000 such villages in Rwanda, including dozens in Kigali, each with an average of 250 people.

Every month, on the last Saturday, villages are legally obliged to come together to participate in Umuganda, a nationwide community service day. Afterwards, villages will meet to discuss community issues, often in the form of directives handed down by the national government, and take decisions. People who don’t toe the line – who have not signed up for mandatory health insurance, for example, or who haven’t delivered on personal behaviour pledges – may be reprimanded or, on occasion, kicked out of the community.

There are elements here of the peer shaming that was so central to chairman Mao’s China, or the totalitarian governments in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. And that, perhaps, is the point – it certainly does allow for extraordinarily direct governance.

But it’s easy to see how such an efficient system can be abused. It offers near-perfect surveillance, and a level of control at an individual level that is nearly unparalleled in the modern world. Big Brother is watching, and no one is talking back.

The undesirables

Anjan Sundaram’s Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship details Rwanda’s suffocation of free press. It ends with a 12-page list of journalists who have allegedly been beaten, tortured, exiled or killed by Kagame’s government. It is not, Sundaram says, an exhaustive list.

The book also touches on other things that Rwanda would prefer to keep quiet. Sundaram follows one story to a rural province, where he finds that people are living in huts without roofs. He says the scene looks like the aftermath of some great tragedy, but when he asks villagers what happened, they tell him that they removed the roofs themselves in response to a government edict forbidding thatched coverings (thatched roofs apparently do not fit in with Rwanda’s modern self-image).

He speaks to one woman as she sat in her newly uncovered house: “She said the president was a kind man for thinking of the poor.”

A local journalist tells Sundaram that the key to understanding Rwanda is not to look at what is there, but at what is not there. Truth is in the gaps. It lies in the unlit dirt paths that commuters still prefer to use; it lies in the lack of meaningful criticism of the president; it lies in the near-complete absence of beggars or homeless people.

Even Singapore has beggars and homeless people.

With no free media or independent civil society to raise the alarm – more glaring absences – it is left to Human Rights Watch to explain where all the poor people are.

“Scores of people, including homeless people, street vendors, street children and other poor people are being rounded up off the streets and detained in ‘transit centres’ or ‘rehabilitation centres’ for prolonged periods. Detainees have inadequate food, water and healthcare; suffer frequent beatings; and rarely leave their filthy, overcrowded rooms,” the rights group said in a July 2016 report.

It said detainees are rarely, if ever, charged, and several have died as a result of their poor treatment.

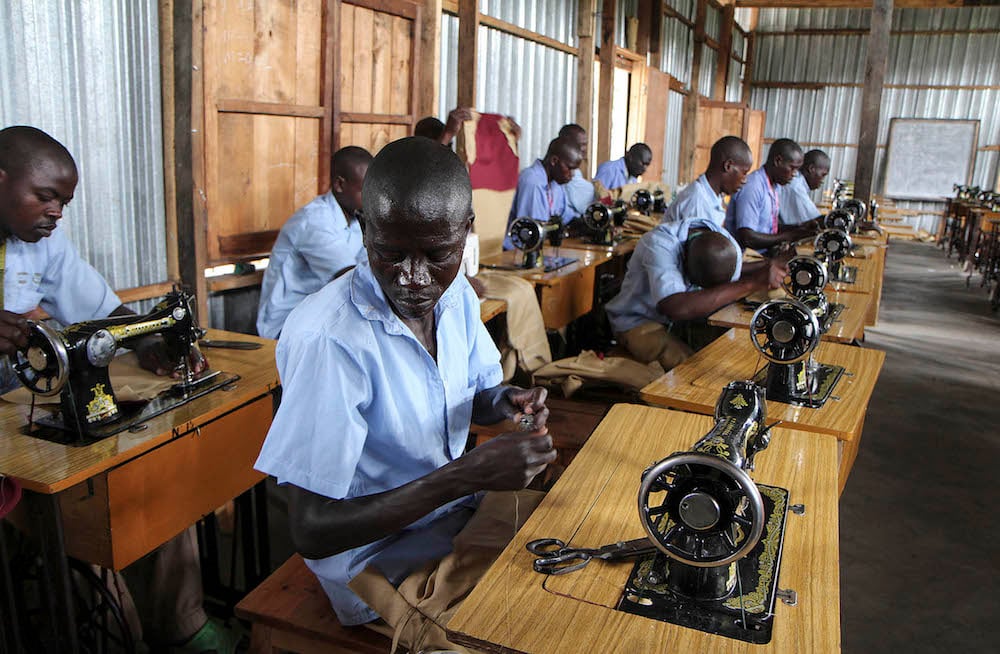

Those deemed unsuitable for society are locked away on Iwawa Island.

(Stephanie Aglietti/AFP)

“The arbitrary arrest of poor people is part of an unofficial government practice to hide ‘undesirable’ people from view, and contrasts with the Rwandan government’s impressive efforts to reduce poverty,” said Human Rights Watch.

One of these detention centres is the notorious Iwawa Island. Officially, it’s a rehabilitation centre for drug addicts, set in the glittering blue waters of Lake Kivu. Unofficially, it’s often described as Rwanda’s Alcatraz, where enemies of the state, along with its poor and homeless, are kept in prison-like conditions.

Illuminée Iragena is another undesirable. She is a nurse and also a member of the United Democratic Forces, an unregistered political party whose members have been repeatedly arrested and intimidated. She left for work at Kigali’s King Faisal Hospital on March 26 2016. She has not been seen since.

“Sources close to the case believe that Illuminée was tortured and died in custody, but have no official information on her fate,” said a spokesperson for Amnesty International. Again, the responsibility for documenting the dark side of Rwanda’s development story falls to international rights groups, because so few inside the country are able to speak up.

Iragena would not be the first opponent of Kagame’s to go missing or die in mysterious circumstances. Even in exile, Rwandans on the wrong side of the regime are not safe: like Patrick Karegeya, the former chief of intelligence who was murdered in a Johannesburg hotel room, or General Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa, the former army boss who has narrowly survived multiple assassination attempts.

The result is that not many are brave enough to take on the regime or to challenge its narrative. August’s upcoming presidential vote is less election and more coronation, and will guarantee Kagame power for another seven years in office.

In private, Rwandan officials and diplomats rarely deny the human rights abuses, but insist that they are necessary to maintain peace and stability.

And in public, Kagame is equally bullish. “Rwandans will not tolerate voices that promote a return to the ethnic divisionism that precipitated the genocide 18 years ago. To that extent, we place limits on freedom of expression in a similar way to how much of Europe has made it a crime to deny the Holocaust. Aside from that, Rwanda is a very open and free country,” he said in 2010.

It has been 23 years since the genocide that killed more than 800 000 people and ripped the country apart, but its memory lives on. On every public building and outside most major businesses are billboards that say: “Kwibuka [Remember in Kinyarwanda] 23. Remember, Unite, Renew. Remember the Genocide against the Tutsi. Fight Genocide Ideology – Build on Our Progress.”

The genocide – against not only the Tutsi people, but also moderate Hutus – was one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century. But it has also become a tool of modern Rwanda’s ruling elite, largely drawn from the Tutsi minority, to suppress criticism and discontent and to justify their continued rule.

Kagame led the force that ended the genocide and therefore to question him is to question the genocide itself. Never mind that Kagame’s forces were also implicated in atrocities – and, later, were to contribute to a devastating war in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo that left millions of civilians dead.

Amid all the publicly organised remembering, plenty more is being forgotten.

In an art gallery in an upscale Kigali suburb, I ask an artist what it’s like to work in this climate of fear. Beautiful paintings hang from the walls. They are mostly pastoral scenes, or abstract. But again, something is missing: there is none of the fierce social and political critique that is such a feature of art elsewhere on the continent.

“We paint pretty things here. We don’t paint politics,” he said.

The trade-off

So this, then, is what Africa’s future looks like: a near-perfect dictatorship that delivers on its promises. A development miracle, achieved at the expense of civil rights.

For Rwanda’s supporters in the African and international community, it is an acceptable trade-off. I suggest to Dr Olu, the WHO’s Rwanda boss, that Rwanda’s development gains are undermined by its notoriously poor record on human rights. He thinks for a minute.

“Let me make clear that I am talking about Africa more generally, not Rwanda specifically. I believe that sometimes the government needs to be a bit firm and decisive. I believe that government needs to take that initiative to act. Sometimes people call these human rights abuses. I disagree.”

And perhaps he has a point. Rwanda is far from perfect, but at least something is going right. The same can’t be said for many African countries that do, superficially at least, support freedom of expression and freedom of opposition but struggle to guarantee these civic and political rights while failing dismally to deliver meaningful development.

One suspects that many Rwandans too, who look back at the country’s history and marvel at how far it has come, accept the trade-off that has been made in their names. Kagame’s popularity is not entirely manufactured. Nor is the progress Rwanda has made, which even his fiercest critics acknowledge is impressive (although some dispute the scale of his achievements, saying that official statistics cannot be relied upon).

It’s easy to see why other African leaders look enviously at what Kagame has achieved. He can not only boast development statistics that his peers can only dream of, but he also gets away with the kind of routine human rights abuses that everyone else is so regularly censured for.

But questions remain: Is Rwanda-style development possible because of its disdain for civil rights, or despite it? Can Kagame, showing every sign of becoming a president for life, keep it up, and can the development outlast him? And, most importantly, is it really applicable elsewhere? The danger is that the repressive elements of the Rwanda model are much easier to replicate than anything else.

Rwanda is an enigma. Whether Kagame is right or wrong, whether he’s a ruthless dictator or visionary saviour, or both, is a debate that won’t be solved for a long time. But given Rwanda’s obvious appeal to the continent’s major power brokers, it’s a debate that Africa needs to be having.

President Paul Kagame is credited with making Rwanda a shining example of a developmental state. Whether he is right or wrong, whether he’s a ruthless dictator or visionary saviour, or both, is a debate that won’t be solved for a long time. (Finbarr O’Reilly/Reuters)