Gordhan did not mention additional funds for the technically insolvent SAA.

The latest bailout to SAA has again highlighted the risk that financially strained state-owned entities pose to the national fiscus.

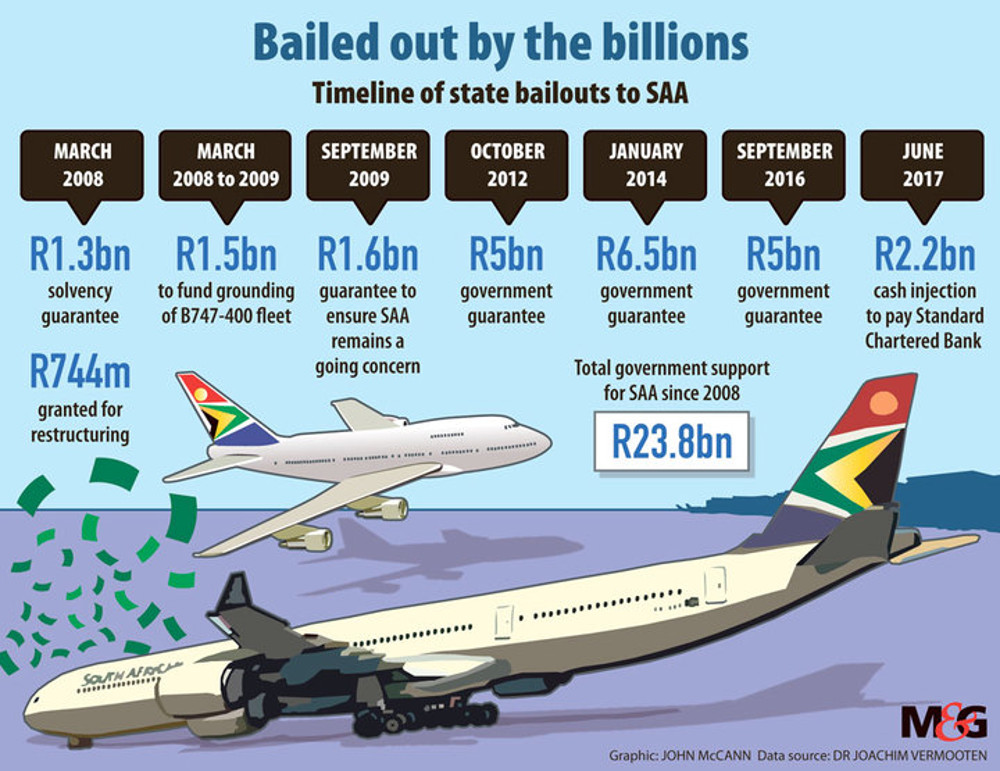

The R2.2-billion cash transfer granted to the airline last week prevented SAA defaulting on its debt and “potential contagion on other [state-owned companies’] guaranteed debt,” the treasury told the Mail & Guardian this week.

The precarious financial state of the airline “remained a risk” to how creditors holding the debt of other state-owned enterprises viewed their investment, it said.

The government’s contingent liabilities, in the form of state-backed guarantees to parastatals and other state agencies, sit at just under R500-billion, or roughly 11% of South Africa’s gross domestic product.

The need for the bailout came after SAA could not repay a loan from Standard Chartered Bank.

The perennial financial instability at the airline has also renewed questions about the need for a state-owned national airline.

The latest bailout brings the total amount of state aid to the carrier — ranging from cash injections to government guarantees on its debt — to almost R24-billion since 2008, according to research by transport economist Dr Joachim Vermooten.

When factoring in the financial support the airline received when it still formed part of fellow state-owned enterprise Transnet, he calculated that SAA has received an estimated R38.5-billion in government financial assistance since 1999.

This is against a backdrop of accumulated losses the airline has suffered over the years, assessed to be in the region of R26-billion by March 2016, according to Vermooten’s calculations. When including the R4.8-billion losses reported to Parliament earlier this year, this brings the figure to R30.8-billion.

In isolation, the R2.2-billion transfer from the national revenue fund to the ailing airline was a “relatively small amount” when compared to South Africa’s overall budget, said Nedbank economist Isaac Matshego. But, he said, it was of “huge concern”.

In the statement announcing the cash injection, the treasury said a default by SAA would have triggered a call on the guarantee provided to the airline, an outflow from the national revenue fund and elevated perceptions of risk regarding the rest of SAA’s guaranteed debt.

But Matshego argued that this was merely semantics and that the bailout could be seen as a call on the guarantee.

“That is basically what happened,” he argued. “Government paid because it had signed a guarantee and SAA could not pay.”

This was “not just about a loan being recalled”, said Matshego, because it raised questions about whether SAA was going to be able to raise commercial debt.

The Standard Chartered Bank loan was part of a total of R9-billion in loans to SAA that matured at the end of June.

But SAA spokesperson Tlali Tlali said the airline was able to renegotiate the terms of the maturing loans and all lenders, except Standard Chartered Bank, had extended their loans. He added that SAA has been able to continue to raise capital in the form of loans with commercial banks.

Treasury, however, confined the financial aid granted to SAA since its transfer from Transnet to a much lower figure of about R4.5-billion. This amount does not include the various guarantees provided over the years, because they do not represent cash given to the company.

The most recent bailout would be budget-neutral but the details of the transaction would only be provided in the upcoming medium-term budget policy statement, it said.

The possibility of merging SAA with smaller regional carrier SA Express, as well as introducing a minority equity partner into SAA as a way to turn its fortunes around, was announced in the 2016 budget.

A “comprehensive assessment” by advisory firm Bain & Company of the options for the optimal ownership and corporate structure for the state-owned airlines had been finalised, treasury said. The next step “is for government to review the options and recommendations to allow an informed decision to be taken on how to proceed”.

International experience showed numerous countries no longer had state-owned national carriers, Vermooten said. In Europe the 25 largest carriers were no longer state-owned and there were instead a number of privately listed flag-bearing airlines, such as British Airways, Lufthansa and Air France.

Airlines, like many businesses, often get into trouble through over-expansion, he said. In the case of airlines this was typically by operating or carrying seats far in excess of their real average demand in the market.

Vermooten said successful airline restructuring programmes had one thing in common: to “reduce the scale of operations and cut costs accordingly”.

At the start of 2012 SAA announced it was launching a “bold new growth” strategy, including a fleet overhaul and several new long-haul destinations such as Beijing. By 2015 the airline had cancelled this loss-making route, which was reportedly costing it R1-billion a year.

Vermooten stressed that at the heart of problems facing SAA was the continued efforts to “expand the loss-making operations of an inefficient, high-cost carrier”.

Concerns have been raised over what the loss of a national carrier would mean for the tourism industry in South Africa. But Vermooten pointed to the example of the Budapest airport after the collapse of Hungary’s national airline, Malev. The airline was the major operator at the airport but it was able to recover — and then exceed — traffic volumes after the entry of other airlines offering services out of the airport.

Domestically, despite SAA ceasing international flights from Cape Town, Cape Town’s airport has seen double-digit growth over the past three years in international traffic.

“The reason for that is that new overseas airlines started to operate directly to Cape Town,” said Vermooten. He added that a number of African airlines have followed suit, and other locally based airlines had started operations from Cape Town to longer distance destinations, bypassing Johannesburg.

“The advantages of larger airlines and the fact that you don’t have to fund them implies that the more you can develop your tourism by getting regular services from foreign airlines, the better,” he said.

In the domestic market it was very clear that the private sector had developed a low-cost market. He said the challenge has been to sustain operations against a competitor that is state-subsidised.

In the domestic realm the probability is new airlines would form, and some of the existing airlines would expand, if SAA were no longer in the picture.

SAA is in the midst of implementing the recommendations of consulting firm Seabury as part of the most recent turnaround plan put in place at the airline.

Tlali said there were a range of short-, medium- and long-term interventions being considered, with some having been implemented as of May. These included “network changes”, as well as the deployment of right-sized equipment to better respond to demand and promote efficiencies, he said.