(John McCann)

Fintech in Africa is generating some of the loudest buzz and attracting the brightest minds and most generous budgetary allocations the continent has to offer. It’s part of a global wave of innovation to meet and shape the changing banking needs of the digital consumer. But many experts say financial technology in Africa is vastly different from fintech elsewhere.

“The way people bank and go about their financial lives in Africa is fundamentally different from other parts of the world,” said Marcello Schermer, who heads up expansion in Africa for fintech company Yoco. “So the way people innovate needs to be different, too.”

It’s limiting to refer to an “Africa” narrative, but most experts agree there are sufficient similarities between countries on the continent to allow for a collective analysis.

“There’s a need to understand both the legal and social idiosyncrasies in each country, but there are certain strong commonalities,” said David Geral, head of the banking and financial services regulatory practice at Bowmans attorneys.

“The level of the banked population is far lower than the rest of the world, the demographic is far younger and the rate at which the middle class will grow is higher.”

Taking these factors into account, Geral said that “the standout successes of fintech in Africa have been needs-driven”. Whereas fintech in other parts of the world might meet consumers’ desires for things such as convenience, much of the innovation in Africa has come about to meet more basic, fundamental needs.

A 2017 Disrupt Africa report, titled Finnovating for Africa: Exploring the African Fintech Ecosystem, shows that payment and remittance startups dominate the market, with 41.5% of startups focused on this space. The report says lending and financing are also “a popular priority for Africa’s fintech innovators”.

African fintech ‘not disruptive’

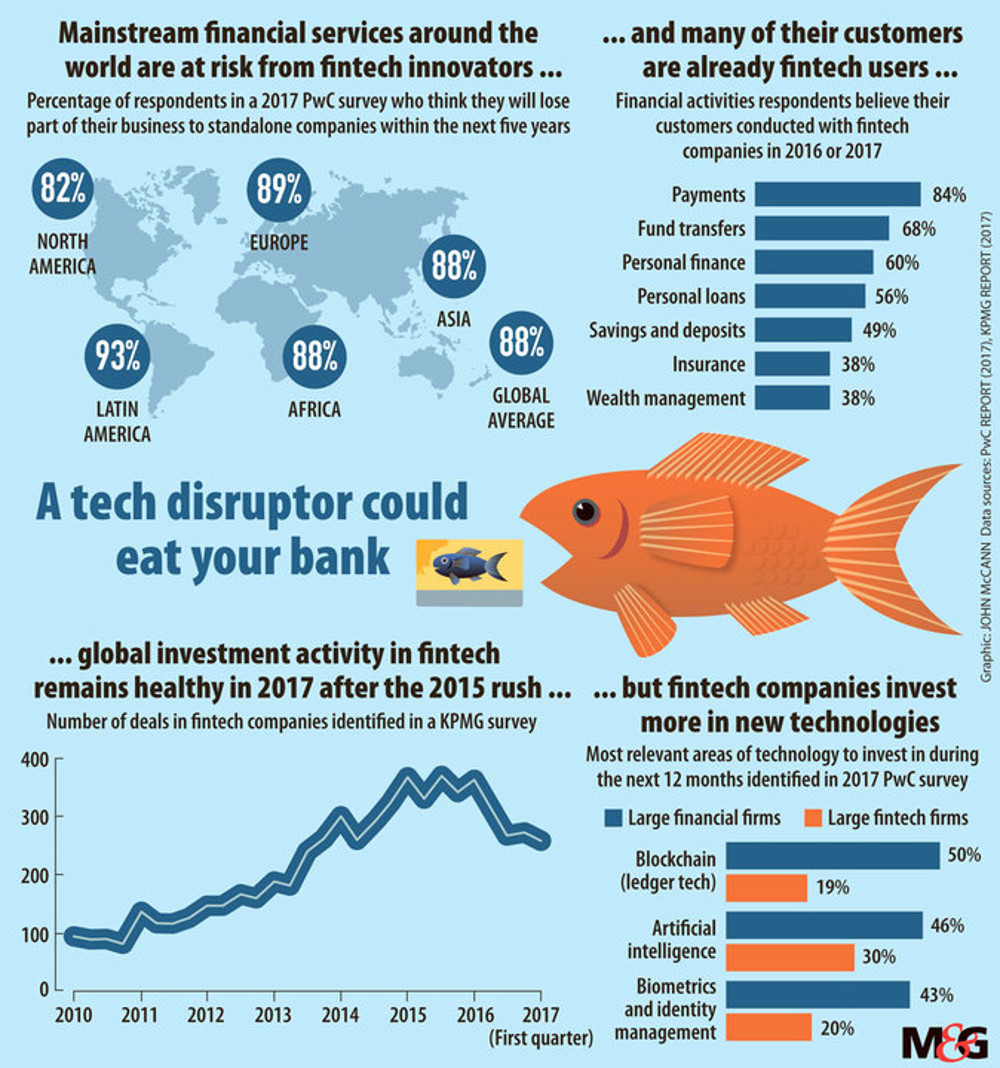

This calls into focus a seemingly sardonic observation by Wim van der Beek, the founder and managing partner of Goodwell Investments: “Whereas in developed economies, fintech is disrupting traditional banks and financial institutions, in most of Africa it is disrupting nothing at all,” he wrote on LinkedIn.

“There is nothing there for it to disrupt. In developed countries, the formal banking system is very widespread, with physical bank branches available in every city, town and village. This is not the case in most of Africa, where it has not been financially viable for banks to offer last-mile services.”

A 2010 McKinsey report pitched the “unbanked” population of sub-Saharan Africa at 80%. Although this number has decreased since then, it is safe to say there are more people who don’t make use of formal or semiformal banking opportunities in Africa than those who do.

“The banking penetration is really low in most of Africa and a lot of people bank on their phones,” said Schermer. “Their wallet is literally their phone.”

In this regard, South Africa is in stark contrast to the rest of the continent. The 2016 FinScope survey on financial inclusion found that, in a nationally representative sample of almost 5 000 adults, 89% of respondents had some type of financial account, formal or informal.

The survey concluded that 38.2‑million adults in South Africa (aged 16 or older) are financially “included”. The remaining 11% of adults, an estimated 4.3-million, are considered financially “excluded”. This figure has remained relatively stable over the past three years, indicating what may be a “saturation of the financial sector”, according to the survey report.

But closer inspection possibly refutes this. The report found that 77% of South Africans had a formal bank account, but when grant recipients were excluded that figure decreased to just over half.

Nevertheless, it’s unsurprising that South Africa is attracting the most fintech start-up activity. According to the Disrupt Africa report, South Africa is home to 31.2% of the continent’s 301 active fintech startups. Nigeria and Kenya are second and third, respectively.

Cultural approach to money

Schermer, who travels extensively across the continent, interfacing with banks and fintech innovators, said he has observed that people “approach money differently from a cultural perspective” in Africa.

“For example, one of the favourite ways to save is in stokvels,” he said. “They use different words for it in different countries, but the concept of community banking exists across the continent. People often choose to save and lend in community groups rather than formal banks.”

Fintech innovations in Africa are springing up to respond to this preference. “You’re now starting to see startups innovating along the stokvel principle,” said Schermer. “They add services to stokvels, for example, offer groups of savers health insurance.”

Locally, entrepreneur Tshepo Moloi has founded StokFella, an app designed for running and growing your own stokvel.

Uniquely placed regulators

Because of the immaturity of the market, Geral has found that regulators in Africa face different challenges to those in other parts of the world.

“Governments in places like the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States have been looking more at issues around competitiveness, data privacy and consumer protection,” said Geral.

“In Africa, it’s often been more about the stability of the financial system, the macroeconomic impact [of a new product] and financial inclusion to some extent.”

As in most parts of the world, innovators have consistently outpaced regulators. Some say this has been a good thing.

“In Kenya, the central bank wasn’t interested in regulating fintech such as M-Pesa,” said Geral, referring to the cellphone-based money transfer product that is used extensively across the country.

“That opened up a space to create a responsive product. In Nigeria, the regulators have been quite strict and we have seen very little fintech innovation take place there.

“It’s appropriate to regulate to protect consumers in that environment,” Geral continued. “But where the regulation is outdated or clumsy, it may impede innovation.”

Geral said South African regulators are moving towards a principles-based approach called sandboxing, which could strike a happy harmony between allowing creativity to flourish and curtailing misbehaviour or abuse in the industry.

“Sandboxing creates a regulatory framework that creates the space for innovators to break the rules — and then demonstrate that breaking the rules is not detrimental in that case,” he said.

It’s one example of how South African regulators are changing the way they regulate to better respond to innovation on the continent.

Regulators in Africa have the opportunity to shape the landscape positively in a way other areas of the world might not. Take Tanzania as an example. In a country where many citizens rely on mobile wallets, the country’s regulators decreed that each “wallet” product should interface with the others, regardless of which bank owned it. This meant consumers could transfer money to users of other products regardless of which wallet they chose to use.

“Mobile wallets aren’t interoperable in a lot of countries. There’s no incentive for the providers to do so,” said Schermer. “But they forced them to interoperate, thereby making it more useful for consumers.”

Space for disruptors

As the banks, telecommunications companies and messaging platforms engage in an energetic battle to capture the “great unbanked” in the rest of Africa, South Africa’s more mature banking environment creates different fintech opportunities to those of its neighbours.

It’s clear the traditional banks are trying to own the fintech space locally, the most obvious sign being the millions of rands they are pouring into their innovation hubs and incubators.

There’s the Alphacode Club, a network started by Rand Merchant Bank aimed at helping fintech entrepreneurs come up with the next big idea for the banking group. Another example is the Barclays Accelerator programme, run by Techstars for fintech start-ups. Standard Bank’s Incubator recently partnered with Silicon Valley-based Startup Grind, a global startup community for entrepreneurs.

“The banks are best positioned to tap into the unbanked market in South Africa,” said Schermer. “But with such a relatively low portion of the population [falling into this category] I’m not sure if they will, because from their position it’s not necessarily worth their while.

“The telcos have burned their fingers too many times trying to get into financial services. That really leaves a massive space for disruptors and innovators who can find a model to serve this part of the market with a much lower cost structure,” he said.

“If they get it right, the banks won’t be able to compete.”