(John McCann)

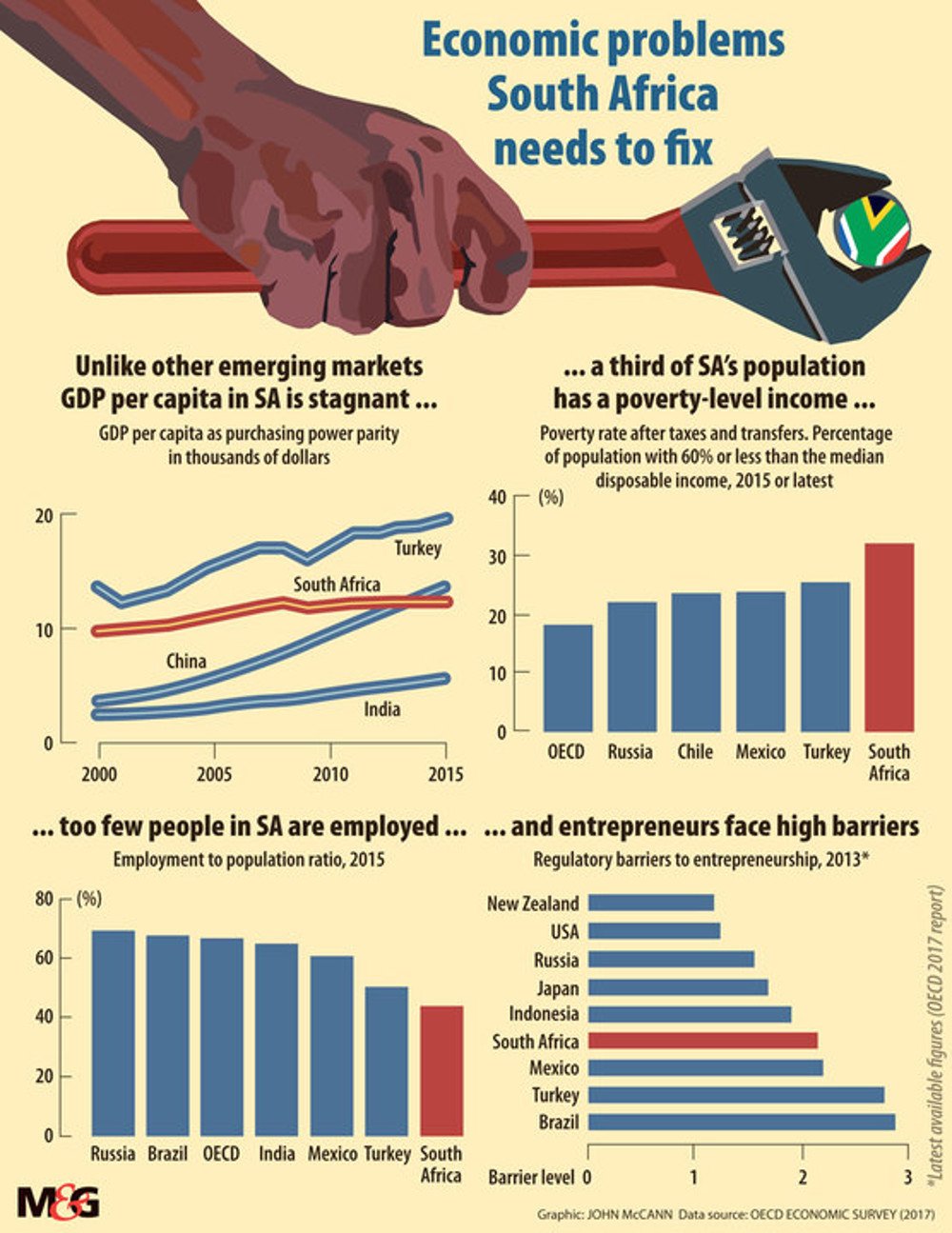

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) this week released its 2017 economic survey on South Africa, which includes data comparing us with other emerging markets.

It found that slow growth — which is likely to continue — and high unemployment will weigh on social progress and cohesion.

Growth has disappointed in the past few years. Weak consumer demand, persistently falling business investment, policy uncertainty and the prolonged drought weighed on activity.

Although power production has improved, important bottlenecks remain in infrastructure and costs of services, which increase the cost of inputs for firms.

The economic slowdown has pushed up unemployment and income inequality is wide. Reviving economic growth is crucial to increase wellbeing, job creation and inclusivity, the survey found. As there is limited room for monetary and fiscal stimulus, bold structural reforms, supported by social partners, are needed to unlock the economy.

Deepening regional integration offers substantial opportunities for South Africa. Despite its large growth potential, economic integration in the subregion has not advanced much. Intraregional trade in the Southern African Development Community is only 10% of total trade compared with about 25% in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations or 40% in the European Union.

South Africa’s weak infrastructure and institutions and barriers to competition limit industrial development. More ambitious and effective infrastructure and investment policies are needed at the regional level.

Boosting entrepreneurship, which is low compared with other emerging economies, is crucial to boost job creation. the survey noted. But slowing growth has compounded an already difficult environment for new and small businesses, and red tape hinders the starting of a business.

The quality of the education system and lack of work experience contribute to gaps in entrepreneurial skills.

There is scope to broaden the sources of finance and government policies should provide more financial and nonfinancial support for entrepreneurs and small businesses. However, a lack of co-ordination and evaluation hampers effective policymaking, the OECD said.

Growth has trended down markedly since 2011 because of constraints on the supply side, in particular electricity shortages, falling commodity prices and policy uncertainty.

Unemployment rose from 25% to 27%. The youth are particularly hard hit, with an unemployment rate of 53% in 2016.

Persistent low growth has led to the stagnation of gross domestic product per capita compared with other fast-growing emerging market economies.

Low growth and high unemployment adversely affect the wellbeing of South Africans, the survey found. The country lags behind the OECD emerging market average in the better life index, in particular in income and wealth, wellbeing and jobs.

Despite increased spending to broaden access to education, its low quality is limiting access to jobs. High crime rates and health problems are also weighing on wellbeing.

But social connections rank high and illustrate the robustness of social institutions and family ties in a difficult economic context.

Also, South Africa performs well in many gender metrics, though there is scope for progress in women’s access to economic opportunities and assets (land, for instance) and in ending violence against women.

Poverty reduction has been limited in recent years. The poverty rate, at about a third of the population, remains high compared with many emerging economies.

The level of inequality also remains high despite important social transfers (16% of government spending in 2016). Grants are the main source of household income for the bottom three quintiles and represent a sizeable share of household income for the fourth quintile. The top quintile earns 40 times more than the lowest.

In addition, continued low growth with rising population growth poses a challenge for government finances. Widespread unmet needs in education, health and infrastructure are also feeding citizens’ frustration, as are perceptions of corruption, the OECD found.

Amendments to the Labour Relations Act, picketing regulations and a Code of Good Practice on collective bargaining, industrial action and picketing are to be promulgated to enhance labour market stability and effective dispute resolution.

To minimise any potential negative effects of the proposed national minimum higher wage, the survey stressed that it is important to pursue structural policy reforms that increase productivity and create jobs. Employment remains the most effective way to reduce poverty and inequality, and increase inclusiveness.

Developing an effective vocational system will help in addressing skills shortages and redirecting the youth back into training, the study said. Only 12% of South African students in upper secondary education were enrolled in vocational programmes in 2013.

Generalising apprenticeship and internship as part of the education curriculum in technical and vocational education and training colleges and universities will favour youth entry in the labour market, said the OECD. Second-chance programmes for adults that build on the existing matric should also be expanded to enable students to re-enter the school system through technical and community colleges.

The economy faces many structural challenges, said the OECD. High inflation limits room for monetary policy support, high public debt constrains public spending, and the high costs of doing business and political uncertainty affect investment and confidence.

Ultimately, South Africa needs structural reforms that would boost the potential of the economy, said the OECD, whose economic surveys of South Africa in 2013 and 2015 pointed to reforms to broaden competition in the economy, limit the size and grip of state-owned enterprises on the economy, and improve the quality of the education system.

This is an edited extract fromt the OECD’s Economic Survey of South Africa 2017