Simon Raubenheimer

Participating in the Barclays PLC sale of more than one-third of South African-listed Barclays Group Africa (BGA) catapulted BGA into a top 10 share across most of our client mandates. Simon Raubenheimer discusses the investment case.

Earlier this quarter our clients had the chance to participate in a rare opportunity: on May 31 2017, UK-based Barclays PLC announced the sale of 33.7% of BGA for R37.7-billion. The placement price of R132 per share was at an almost 10% discount to the closing share price on the day before the announcement and the average price over the preceding month. At very short notice our clients got to invest a substantial sum of money in a decent asset, at a great price.

Barclays PLC’s history with Barclays Group Africa

The lion’s share of Barclays PLC’s investment in what was then called Absa was made in 2005 at R82.50 (or £8 per share from their perspective). A further investment was made in 2013 (share price £9.50), coinciding with a name change to BGA. By March 2016 Barclays PLC — now under a new chief executive — reversed course and announced its intention to sell the bulk of its 62.3% in BGA. A chunk was sold off in May 2016 at £5.80/share and the recent sale at £7.80 will leave Barclays PLC with around 15% of BGA (which may soon be called Absa).

From Barclays PLC’s perspective their investment in BGA has been disappointing: in British pound terms, we estimate that Barclays PLC generated marginal positive returns after accounting for BGA’s generous ordinary and special dividends and R12.8-billion of separation fees.

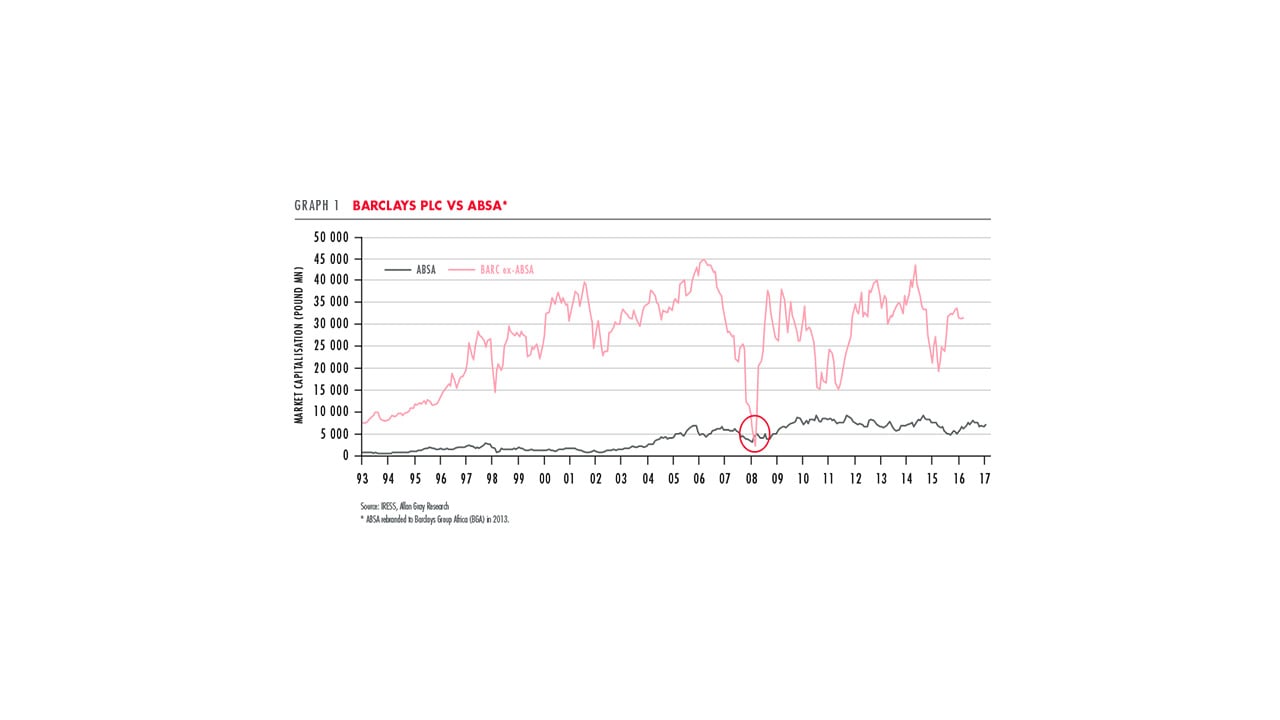

Barclays PLC’s investment would have lagged the South African FTSE/JSE All Share Index by at least 5% per annum. It is staggering that in early 2009, at the trough of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the 320-year old Barclays PLC (excluding its stake in Absa) — with over 100 000 employees around the world and assets of £1.3-trillion — had a market value lower than Absa’s (which at the time had total assets of only £60-billion, less than 1/20th of Barclays PLC). Just seven years prior to this, Barclay’s PLC was 35 times bigger than Absa, as shown in Graph 1. The performance of our banks during the GFC is testament to the stability of our banking system.

The South African banking sector

Our major banks have all grown their earnings faster than the market over the long term, and the banking sector overall has done well for all stakeholders. We are not oblivious to the challenging economic climate currently facing the banking sector. Weak economic growth and political instability are legitimate concerns. Rating downgrades carry real economic consequences through higher costs of capital and lower returns on equity for the banks. However, these concerns are well known and widely publicised.

Importantly, however, the fundamentals underpinning the South African banking system have not changed. It is vital not to lose sight of the long-term picture amid all the noise and hysteria. Our banking sector remains a small, conservative and tightly regulated industry operating in a largely closed currency system. The following factors suggest that current banking industry profits are not high:

- Slow credit growth: private sector credit extension expressed as a percentage of GDP is flat on a decade ago and well below its previous high (see Graph 2). Bank clients are less indebted now, on average, than they were 10 years ago.

- Muted asset price growth: Capetonians might find this hard to believe, but South African house prices, on average, have not kept up with inflation for 12 years.

- Conservative provisioning: Post-GFC, post-African Bank — South African banks are cautious. Portfolio provisions are at their highest levels in over a decade. Provisioning entails sacrificing today’s profits to buffer future profits against potentially adverse developments.

- Increased regulation: Globally as well as locally, banks are more heavily regulated than in the past. As a consequence, their assets are supported by higher levels of equity and lower levels of debt, and the riskiness of both their assets and liabilities is reduced.

- Long-term upside to financial penetration: 65% of transactions in South Africa are still done in cash. Excluding South African Social Security Agency cardholders, 58% of South African adults are banked. Only 14% of South Africans borrow from banking institutions. Credit card penetration is estimated to be around 17%; mortgage penetration a mere 5%.

BGA in the South African context

BGA’s earnings growth has lagged its competitors by a few percentage points every year over the past five years. With hindsight the bank made a few strategic errors: credit was tightened too aggressively after the GFC, the product offering became too expensive and lagged its peers in terms of digital functionality. Clients who wanted personal and home loans simply moved their accounts elsewhere.

BGA’s challenge now is to stem the tide and re-ignite some growth in its top line. The bank has a big market share in critical areas but it is losing ground to competitors.

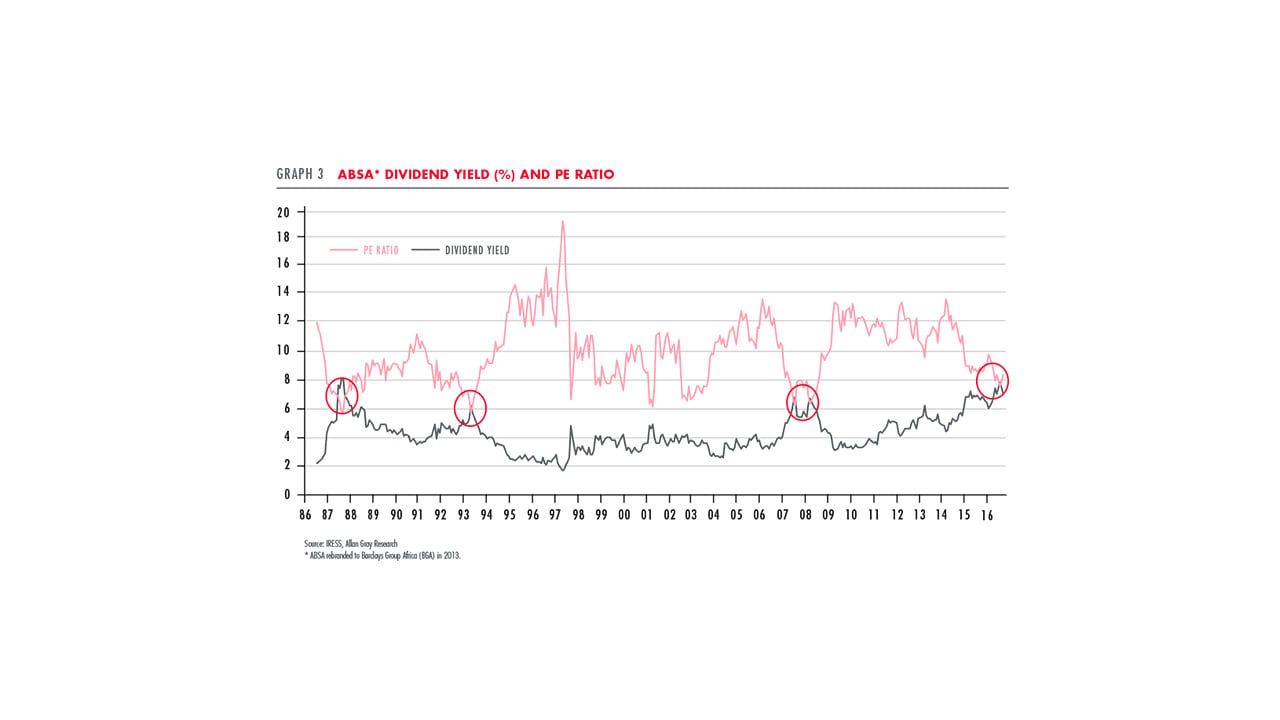

Tough times can have a silver lining if they gift us the opportunity to buy assets at bargain prices. This might classify as one such opportunity: our recent investment in BGA was at a multiple of 7.5 times its most recent earnings and a dividend yield of 7.8%. It is not everyday that one sees dividend yields higher than price-to-earnings (PE) ratios on the JSE, as shown in Graph 3.

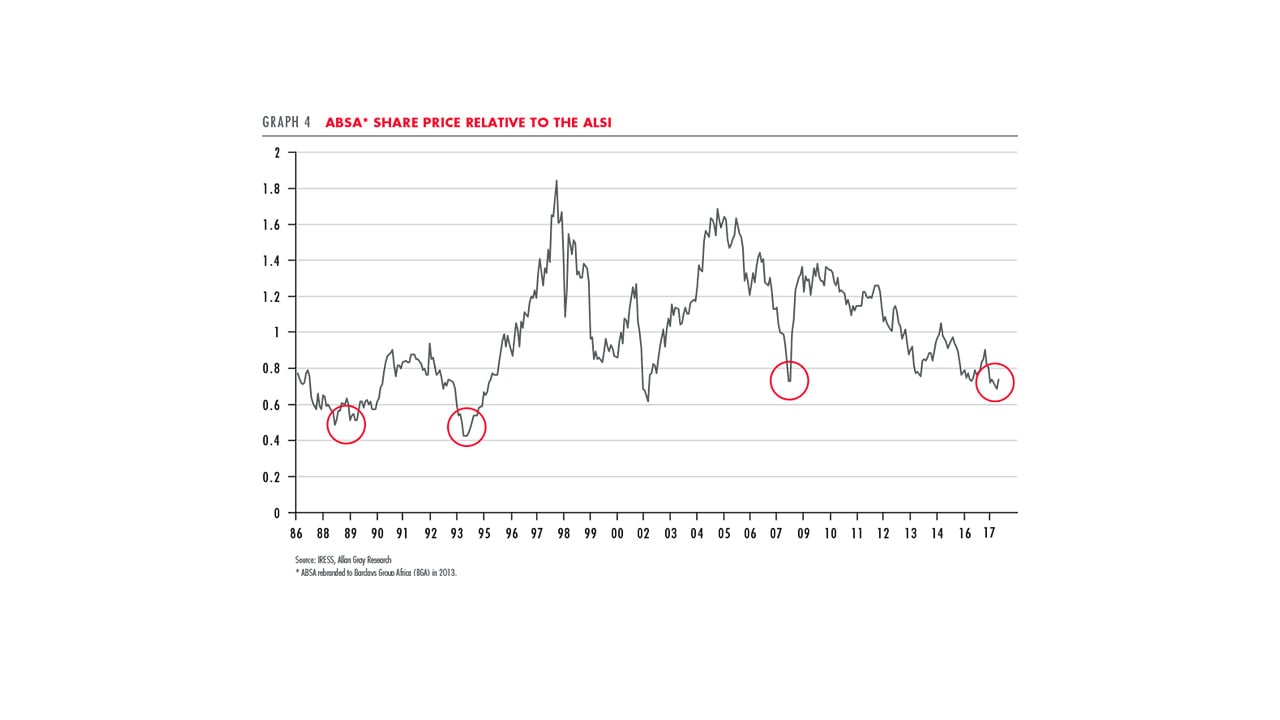

Absa’s PE ratio has been lower than its dividend yield on only three occasions in the history that we have for the bank (or its predecessor United Bank, given that Absa was only established in 1991): 1988, 1994 and 2008. All those times were characterised by massive uncertainty and investor distress. And in all cases investors would have done well over the subsequent three to four years, as reflected in Graph 4.

BGA’s PE ratio is currently at a 60% discount to the average company listed in South Africa — a level only seen twice before (1994 and 2008). Similarly, its dividend yield is 1.7 times the dividend yield of the average company, matched only in 1994 and 2008. There is indeed some evidence of matters slowly improving:

- Better pricing: from being the most expensive six years ago, Absa’s entry level account is now among the cheapest in South Africa, according to some surveys.

- Improved transactional banking offering: including first-to-market innovations, such as “ChatBanking” (transacting via social media) and the world’s first trade finance transaction using Blockchain.

- Happier clients: their net promoter score has improved for four consecutive years. Customer satisfaction surveys are showing improvements.

- Happier staff: employee engagement scores are trending up.

It takes a long time to turn a big ship around. The market doesn’t believe in BGA’s recovery and expectations are low. As a long-term investor, this negative sentiment is in our favour.

Patient capital “on the sideline”

In the absence of a crystal ball, it is impossible to accurately predict market movements or to foresee a sudden opportunity in shares we like. But we know that, from time to time, the unexpected will happen, and we need to be prepared. Three things enable us to react to opportunities with conviction:

1. Thorough and up-to-date research: we research all the companies in our investment universe, whether our clients own them or not.

2.Access to liquidity: across our Equity, Balanced and Stable mandates, we keep a percentage of the funds in cash to participate in unforeseen events. In a rising stock market, this causes a slight drag on performance, but the option of deploying the cash profitably outweighs the cost.

3.Benchmark agnosticism: if we like a company, we will invest with confidence irrespective of the size of the company, our peer group holdings or weight in the benchmark.

These factors continue to allow us to react to opportunities that will hopefully contribute to future outperformance.