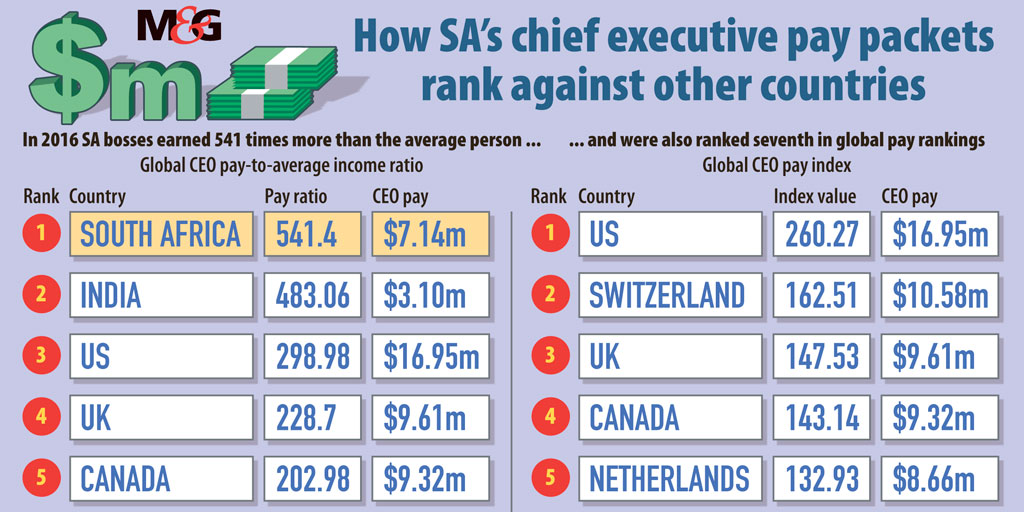

In 2016 a Bloomberg analysis revealed that South African chief executives ranked seventh in the world in terms of average pay.

Rules to curb chief executives’ income in the United Kingdom appear to be working, which raises the question: Should South Africa start regulating how top corporate leaders get paid?

This week the UK arm of consultancy firm Deloitte released a preview of its annual FTSE 100 executive remuneration report. The preview showed that the median income for chief executives of the top 100 listed companies has fallen by almost 20% from £4.3-million in 2016 to £3.5-million this year.

This is the first year when the effects of tougher legislation governing executives’ pay packages introduced in 2013 will have been felt, suggesting that it is working, Deloitte vice-chairperson Stephen Cahill said in a statement.

That legislation required, among other things, that listed firms disclose a director’s remuneration policy, which is put to a binding vote by shareholders every three years.

These findings come amid reports of large JSE firms such as Naspers facing shareholder pushback over remuneration for its executives, notably chief executive Bob van Dijk.

Van Dijk’s fixed pay rose by 11.2% to more than $1.1-million, and his annual performance bonus increased by more than 70% to $973 000, according to the company’s latest financial results.

Business Day reported that institutional shareholders such as Allan Gray are preparing to take Naspers on over its pay policy at its annual general meeting on Friday, particularly as the company’s outperformance is being driven by its investment in Chinese tech giant Tencent.

Shareholder activists and experts are sceptical about the value of introducing strict legislation dictating how companies pay top leaders. But South Africa’s persistently high levels of inequality continue to fuel the debate about executives’ earnings.

The controversial R30-million pension payment to former Eskom chief executive Brian Molefe prompted trade union federation Cosatu to renew calls for regulations to curb executive remuneration in both the public and private sectors.

The Deloitte findings mirror those of another UK report released jointly earlier this month by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, a human resources professionals body, and the High Pay Centre, a think-tank that looks at issues such as top incomes and corporate governance.

The report found that chief executives in the UK’s FTSE 100 companies have seen their remuneration drop by 17%. The average pay package went from £5.4-million in 2015 to £4.5-million in 2016.

Similarly, the pay ratios — illustrating the difference between what top bosses and the lowest-paid workers earned — also saw a decline. The average pay ratio between FTSE 100 chief executives and their employees was 129:1 in 2016, falling from 148:1 in 2015. In other words, for every £1 the average worker earns, their CEO received £129

In South Africa there are “hard” disclosure and approval requirements through legislation such as the Companies Act and the JSE’s listing requirements, said Ray Harraway, chair of the remuneration committee forum at the Institute of Directors Southern Africa.

But there are no rules that specify how much executives should be paid, he said, apart from in certain sectors such as banking and insurance where, for example, payment of short-term bonuses must be deferred over a period.

The most recent iterations of the King Code on corporate governance for South Africa — King III and King IV — do, however, recommend implementing certain pay practices.

Despite this, executives’ pay has continued to grow in recent years.

A recent Deloitte South Africa report on executives’ remuneration at the top 100 JSE-listed companies found that, over the past five years, increases in chief executives’ guaranteed pay exceeded inflation by considerable margins. And annual cash incentives paid to chief executives and chief financial officers over the past six years “are considerable in relation to guaranteed pay, but with little indication of the performance linkages”.

A recent remuneration report by another of the “big four” consultancy firms, PwC, found that the average total guaranteed package for the top 10 firms on the JSE (accounting for 60% of its market capitalisation) was R24.6‑million. The total guaranteed package is the portion of remuneration that is paid regardless of company or employee performance, and is a fixed cost made up of salary plus stated benefits.

In 2016 a Bloomberg analysis revealed that South African chief executives ranked seventh in the world in terms of average pay. But when comparing top bosses’ pay with that of the average income of ordinary individuals — where they earned more than 500 times more — South Africa shot to the top spot.

In the United States, a rule has been introduced requiring companies to disclose a ratio comparing what chief executives earn with the median salary of their workforce. Companies are expected to begin disclosing these figures from early 2018 onwards, although there have been reports of concerns that Donald Trump’s administration could delay implementation.

Shareholder activist Theo Botha was sceptical that tougher legislation or regulation governing executives’ pay would work in South Africa, in part because it increased compliance costs for companies.

“What we need is responsible share owners,” argued Botha — particularly institutional investors such as asset managers who own shares on behalf of their clients.

But Botha did say that pay ratio reporting could be useful and should be introduced through the likes of the King Code. “We have to see who is shooting out the lights in terms of payment,” he said.

According to Harraway, King IV — which took effect for companies with financial years starting April 1 this year — calls for more specific disclosure “on both the how and the how much”, compared with its predecessor.

More transparency is expected to demonstrate the arrangements made by companies to ensure pay is fair in the context of the broader workforce, he said.

King IV also provides shareholders with more opportunity to get involved in the remuneration matters of the company, he said, including by presenting them with a nonbinding advisory vote on the remuneration policy (the “how”) and the pay outcomes of the policy (the “how much”). If 25% or more failed votes are received, companies are obliged to discuss these policies with their shareholders and to disclose the planned remedial action.

Although South Africa had no firm legislation to enforce a binding “say on pay for executives”, said Leslie Yuill of Deloitte, directors are elected by shareholders to act in the best interests of the company and they can replace them when they are not doing so.

The advent of King IV is “a step in the right direction”, he said, and “will engender a greater level of debate between shareholders and nonexecutive directors as well as improving the quality executive remuneration disclosure in South Africa”.

Gerald Seegers, director at PwC, did not believe that legislation would necessarily work in South Africa, and argued that the approach embodied in the King Code — to “drive best practice” — allowed companies more flexibility in the approach they took to executive pay.

The “voices of institutional investors” are increasingly becoming more powerful, Seegers said. “Institutional investors are really taking King IV to heart.”

Ratio reporting, similar to what is in place in the US, is useful as an internal measure and is something that board remuneration committees should consider, he added.

He was sceptical, however, of the usefulness of identifying and publicly reporting a hard and fast ratio as a gold standard in South Africa, given the difficulties in benchmarking these figures.