New data from Stats SA show that

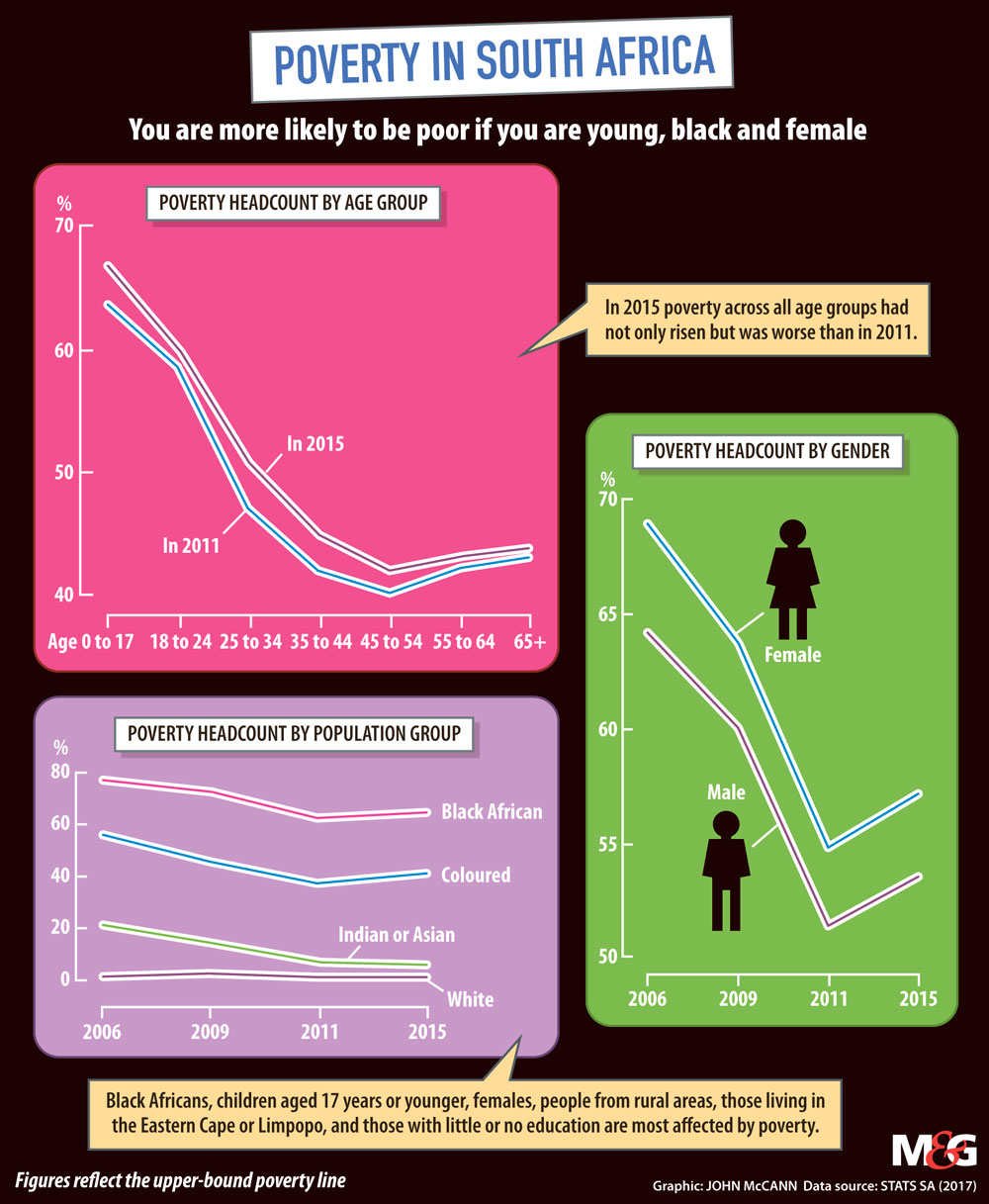

New data from Stats SA show that, despite a decline in poverty between 2006 and 2013, it has started to rise again. The latest Poverty Trends in South Africa report reveals that one in three South Africans lived on less than R797 a month in 2015.

Women, children, people from rural areas and those with little or no education are the most affected. Gauteng has the lowest percentage of those below the poverty line, and many move to Johannesburg for better job opportunities. The Mail & Guardian spoke to some of the people for whom poverty is daily life. Here are their stories:

Elsie Molefe (55)

Elsie Molefe lives with her sister, Caroline Molefe (53), and two of her four children. Her other children are in Zeerust where Elsie lived before her father died.

[Elsie Molefe is among the many who have to survive on very little. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)]

Before moving to Joburg, Elsie and her family depended on their father’s social grant while she took care of him back home. A short while after his death, one of Elsie’s children was stabbed and killed. The children’s father was also killed.

Elsie now relies on child support grants that she says amounts to R690 — she laughs at the grant increase of R10 per child. She sends some of this money home, but most of it goes to sending her two youngest to school. Transport to school in Witkoppen costs R380 per child per month. To supplement the price of schooling, Elsie sells “magwinya, ama kip kip and sweets” outside the school down the road. If she could, she says she’d return to the North West to “live a good and comfortable life”.

Violet Matsaung (39)

Violet Matsaung lives in one of three one-room homes surrounding Ratanang Daycare in Diepsloot Extension Six.

[Violet Matsaung (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)]

It is a good location for a mother with children, one of them a one-month-old baby. Despite leaving her home in Ga-Mashashane to look for job opportunities in Johannesburg, Matsaung has been unemployed for the past two years.

To provide for her four children who live with her, she relies on social grants of R380 a child and assistance from her partner. She has not yet registered her youngest for a grant. The money is spent on food, paraffin and school fees. Anything she has left is put aside for medical emergencies and to help her 18-year-old in Limpopo finish school.

There is little, if anything, left to cover crises, such as an open sewer pipe that runs through Matsaung’s home. “When it rains, the water floods our yards and shacks,” she says. She hopes that in the wet season the rains will end quickly and her children will stay healthy.

Thomas Ncube (46)

“I do have things [dreams and hopes] and I do think about them but what can you do if you don’t get a proper job? What can you say? It hurts to think about these dreams I have but not be able to do anything about it so I try forget them. I don’t think about them. I don’t have a choice.” Ncube’s grin doesn’t quite reach his eyes as he looks down at his hands, shrugs and pulls down on his cap. “Hai sesi, I just forget because it’s better that way.”

[Thomas Ncube (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)]

Thomas Ncube works odd jobs painting houses but is currently unemployed and selling ama kip kip and other snacks from his makeshift spaza on the street corner. His three children are being raised by his ou lady (mother)back home in Zimbabwe and since the children were born in South Africa, Ncube approximately receives R380 per child in grant money which he sends home.

Ncube points to the spaza where his wife sits in the sun next to the wheelbarrow that helps them carry the stock: “My wife was a domestic worker but it’s been uhm, three years since her job ended. When I can’t find a piece job, the spaza is the only way I can try get money for us to live.”

Clementine Ntuli (31)

Clementine Ntuli lives in a one-room house in Mayville, Durban, with her six children and a grandchild. A heart condition means she has struggled to work. Her sister lives in a neighbouring shack. She too is unemployed and can’t support Ntuli. “There is no one helping. No income.”

[Clementine Ntuli (Madelene Cronje/M&G)]

Ntuli’s parents died when she was young, leaving her without the documentation to get an ID book, which means that Ntuli cannot apply for social grants for her children. She has applied for an ID many times, but she has no living family member who is five years her senior to vouch for her South African nationality.

Ntuli depends on food parcels donated by staff from eThekwini municipality to the Highway Hospice. “If it wasn’t for the food parcels, we’d go hungry,” says Ntuli. The parcel of tinned fish and beans, one kilogram of rice, milk, mealie meal, jam, samp, sugar and tea lasts a week, leaving Ntuli and her family living on leftovers from a school feeding programme.

Moipone Badise (30)

For Moipone Badise, the plan was never to be in Diepsloot visiting friends, making long distance calls to her three children and attending weekday prayer meetings. Badise had aspirations to turn her love for caregiving into a nursing career at home. But her sister’s recent death has led Badise to make decisions that she did not bargain for.

[Moipane Badise (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)]

Badise left her three children in Vryburg to care for her sister’s son. The thirty year old receives a grant of R360 for each of her three children and sighs about how far she has to stretch it. “Things are expensive and R360 does nothing. For example, how much does it cost for a child to be at crèche, vele?” And before she is done thinking of her children’s needs, Badise has to consider her nephew.

Lacking skills, Badise’s countless repulses has left here dejected in her search for employment. The social grant does not fully cover her basic requirements. “So where I stay here [in Diepsloot], I rent out the back rooms. It’s not what I want but I need the income.” For now she focuses her energies squarely on the survival of her children.— Compiled by M&G interns Mashadi Kekana, Gemma Ritchie, Sarah Smit and Nkosazana Hlalethwa