Lion’s share: Freedom Front Plus MP Corné Mulder has questioned the 90/10 funding allocation to parties

It took more than a month for the treasury and the Independent Electoral Commission to add up just how much public money is flowing into the private banks of political parties from various sources. And when they found out, this was pretty much all the information that they could provide.

The answer is R1.09-billion. A year. And it’s rising at a rate of about 10% a year.

The ANC is probably receiving more than R600-million a year, not from private donors, the Guptas or state-owned enterprises but from the public. And it’s all legal. For now.

As the Constitutional Court has pointed out, political parties are an integral part of modern South Africa’s democracy and so the public investment makes constitutional sense, not least because section 236 of the Constitution requires public funding of political parties.

They incur significant expenditure going about a task without which we would have no democracy at all and smaller parties especially cannot rely on wealthy private donors to fill their pockets.

But it is also a highly controversial subject: Is it a wise and justifiable investment in public resources, particularly at a time when the national fiscus is under great pressure?

[The number of MPs per party determines the amount the parties get (Liza van Deventer & David Harrison)]

Moreover, there is uncertainty about where as much as R949-million of the total public spend on political parties is ending up and how it is being spent. This is according to evidence that emerged during the recent parliamentary ad hoc committee hearings on party political funding. A draft Bill, covering private and public funding, was published by the committee on September 15.

Political parties receive public money in three forms. The first is from the Represented Political Party Fund (RPPF), created by the Public Funding of Represented Political Parties Act of 1997. The second two are allocations by the National Assembly and the provincial legislatures to fulfil the constitutional requirement to “enable the party and its leader to perform their functions … effectively.”

There are huge problems with all three.

Although the RPPF accounts for the smallest percentage of the funds, it is arguably the most significant, for two reasons. The first is that, unlike the other two sources, these funds are made available to parties for a broader range of activities, including campaigning, a vital party activity, which falls out of the scope of the funding that parties receive from the national and provincial legislatures.

The second reason is that, unlike the funding allocated by the national and provincial legislatures, we know exactly where it is going and how it is being spent. And the results are shocking.

Section 236 of the Constitution states: “To enhance multi-party democracy, national legislation must provide for the funding of political parties participating in national and provincial legislatures on an equitable and proportional basis.”

Therefore, the Constitution envisages a balance between the principles of proportionality and equity in the formula for the allocation of these funds, but the determination of that formula is not specified. The regulations ostensibly agreed to in 1997 by the (then) biggest parties, the ANC and the National Party, provide that 90% of the funds are allocated proportionally and just 10% on the basis of equity.

[Skewed: The small parties get very little and the majority party, the ANC, gets the most (Madelene Cronjé)]

So why did Parliament decide that the principle of proportionality should so heavily outweigh the principle of equity when the Constitution provides no hint that either of these principles should be favoured?

Freedom Front Plus (FF+) MP Dr Corné Mulder, an experienced parliamentarian who has been a forerunner in bringing this particular problem to light for many years, says that the 90/10 split was agreed to even earlier, during the 1994 negotiations for the new Constitution, and was the “product of a deal” between ANC MP Pieter Hendriks and National Party MP Con Botha to keep the bulk of the funding for the two largest parties, the latter operating under the mistaken belief they would remain a major party in the constitutional era.

The original rationale is clearly obsolete, but the more pressing question is whether the formula is constitutional at all. Because the 90/10 split was enacted to fulfil a constitutional provision, it must fulfil that — to “enhance multi-party democracy” — to pass constitutional muster.

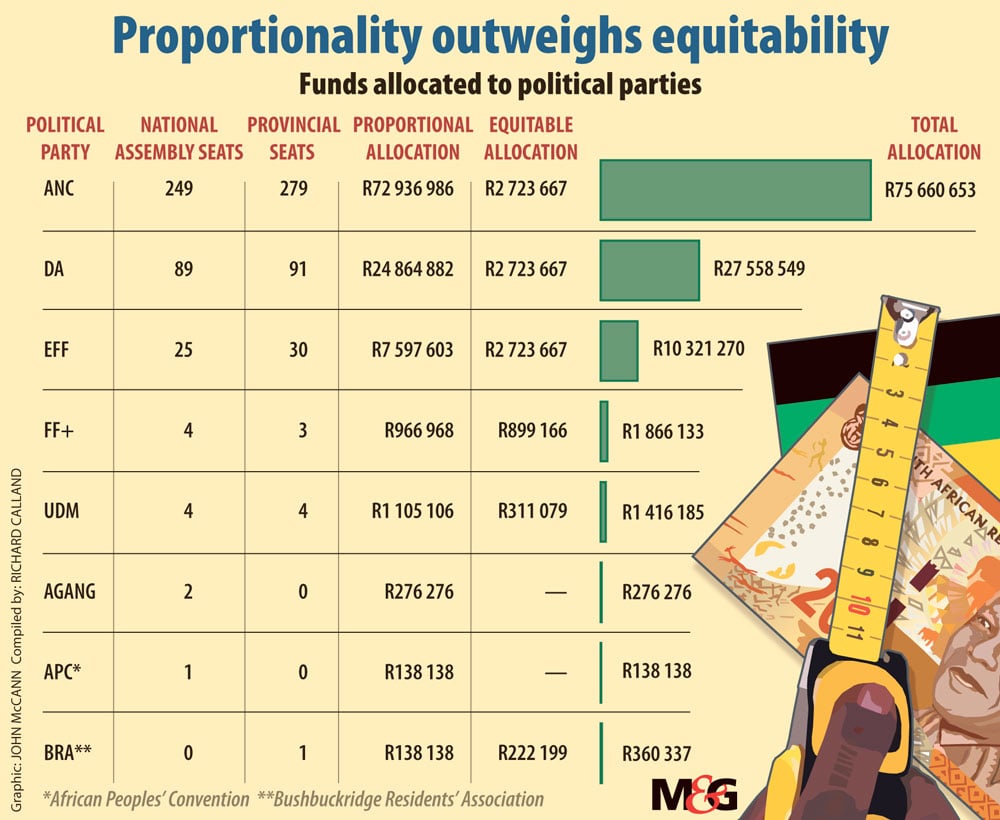

But the current formula does not do that; in fact, it does the opposite. The 90/10 split hugely favours the larger parties at the expense of smaller parties. For example, the ANC received R75 660 653 from this allocation in 2016 but the African People’s Convention and Pan Africanist Congress, which are both represented in the National Assembly, received a meagre R138 138 each. The Congress of the People (or Cope), the FF+ and the United Democratic Movement, which are all well-established parties in Parliament, each received less than R2-million — about R73-million less than the ANC.

It is a classic case of the “rich get richer while the poor get poorer”.

Does the “equitable” element correct the balance? Our new research suggests that the answer is a resounding no. The formula for the equitable allocation is complicated but the net result is that the equitable allocation isn’t equitable at all. (See “Some are more equal than others” and “How do the formulas work?”)

Parties receive additional funding to function effectively in the national and provincial legislatures. In terms of section 57 of the Constitution, political parties in the National Assembly will receive R414-million for this during the 2017-2018 financial year and, in terms of section 116 of the Constitution, for the same period, they will receive an additional R535-million for their activities in provincial legislatures.

One problem with these sections is that there is no provision for an equitable allocation and it is being split proportionally.

But the most pressing issue is that the legislation that was enacted to give effect to these sections, the Financial Management of Parliament and Provincial Legislatures Act of 2009, requires regulations to be issued to provide for the allocation of these funds and the purposes for which they may be spent, but these regulations are lacking.

This led to an alarming revelation during the treasury’s submission to the ad hoc committee: apparently it is the practice of some provincial legislatures to allocate each party a lump sum, which they can spend as they wish.

This is clearly incompatible with the purpose of sections 57 and 116. This funding is aimed at assisting parties in their parliamentary duties only. Such activities may include travel costs, administrative costs and office rentals. But the lack of regulations and disclosure provisions make it almost impossible to track how this money is allocated and whether it is being spent on its constitutional purpose.

So, the bottom line is this: R1.09-billion is being given to political parties from the public purse. It is allocated in a manner that strongly favours the larger parties, cripples the smaller ones and does the exact opposite of what it’s supposed to do, which is to enhance multiparty democracy. Furthermore, about 85% of this money is being allocated in a manner that is essentially untraceable and clearly unconstitutional.

The current parliamentary reform process, which will also bring much-needed reform to private donations to political parties, has the opportunity to take the requisite steps to address these issues.

This is essential for the future legitimacy of political party funding. The public is unlikely to stomach the current system of public funding unless both it and private funding are subject to far greater levels of legally enforceable transparency and accountability. Why should the public fund political parties in the dark?

How do the formulas work?

The proportional allocation

The proportional allocation goes to parties that hold seats in both the National Assembly and provincial legislatures.

The total number of seats in these legislatures is 830. The allocation is made in proportion to the total percentage of the seats that each party holds. For example, the ANC has 249 seats in the National Assembly and 279 in the provincial legislatures. Therefore, it holds 528 of the 830 seats (63.6%) and receives 63.6% of the total proportional allocation.

The equitable allocation

The equitable allocation goes to parties that hold seats in the provincial legislatures only, and is divided up as follows:

- Step one: Determine the total number of seats in the provincial legislatures (430).

- Step two: Consider each province individually to determine the proportion of the 430 seats that are included in that provincial legislatures. For example, the Western Cape has 42 (9.8%) of the total provincial seats.

- Step three: Divide the equitable allocation in relation to each province’s share of the total provincial seats. For example, parties in the Western Cape provincial legislature will therefore receive 9.8% of the total equitable allocation.

- Step four: Divide the allocation made in respect of each province equally between all parties represented in that province. For example, there are four parties represented in the Western Cape and each gets a quarter of the 9.8% of the equitable allocation in step three.

Therefore, the ANC, the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters all get such a high proportion of the equitable allocation because they are the only three parties that are represented in all nine provinces and therefore get nine cuts of the equitable allocation. By contrast, the United Democratic Movement holds four provincial seats but, as all those seats are in the Eastern Cape, they only get one cut of the equitable allocation.

Some are more equal than others

The total amount of the equitable allocation is currently R12 739 415.

Of this amount, the ANC, the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters each receive R2 723 667.

This means that, together, these three, out of the 15 parties, receive a total of R8 171 001 (or 64.1%) of the “equitable allocation”.

Agang, the African People’s Convention and the Pan African Congress all hold at least one seat in the National Assembly, but none of them receive anything from the equitable allocation.

The Bushbuckridge Residents’ Association has no seats in the National Assembly, but one seat in the Mpumalanga Provincial Legislature, and they receive R222 199 from the equitable allocation. By contrast, Agang has two seats in the National Assembly and, in the 2014 national elections, it received more than three times the number of votes than the Bushbuckridge Residents’ Association. The association received almost R100 000 more than Agang in terms of the overall allocation from the proportional and equitable allocations combined, and R222 199 more than Agang from the equitable allocation alone.

If you add the up the combined equitable allocations of the parties that came fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh — the Inkatha Freedom Party, United Democratic Movement, the National Freedom Party and the Freedom Front Plus — in the 2014 national elections, the amount is still less than the equitable allocation of the party that came third, the EFF.

Both the UDM and the FF+ have four seats in the National Assembly. The UDM has four additional seats in the provincial legislatures and the FF+ only has three. But the FF+ receives over R400 000 more than the UDM in terms of the overall allocation.

The “value” of holding a single seat in KwaZulu-Natal is worth almost double the amount of money as holding a seat in the Western Cape.

Richard Calland is associate professor of public law at the University of Cape Town and a member of the advisory council of the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution, for whom Mike Law conducted the research that informed its submission to the ad hoc committee and gathered and analysed the information presented here