'Since time is distance in space'

I was not prepared to meet Mame-Diarra Niang. Prior to landing at her studio residency on the upper gallery of the Stevenson gallery, I had only glanced, quite quickly, at Niang’s photographic series, in particular Sahel Gris, At the Wall and Metropolis.

The drive to her temporary studio (from Rosebank to Braamfontein) somehow mimicked the meter and methodology of Metropolis, her in-motion series of buildings in Johannesburg’s inner city. In that series, Niang seems to alter the dimensions of the city’s skyscrapers, splitting their pretences towards location and reshaping them into a city refracted through the prism of time.

Looking at Metropolis while moving through the city lent a poetry to my anxiety.

Moving backwards through her oeuvre, it was easy for me to see, for example, how Origin of the Future (depicted on her website as a series of fragmented, reconstructed geological stills) could be directly related to, say, At the Wall, her Dakar series playing with stillness and optical perspective. In a sense, both capture “imaginary territory constructed out of lost physical territories”.

Seeing Origin of the Future for the first time before the studio visit evoked a feeling of being trapped inside a city’s bowels, contrasting with the feeling of experiencing its temporality that occurs with Metropolis.

Whereas Metropolis transforms Johannesburg’s edifices into geometric, pyramid-like shapes, as if conjoining both its past and future, Origin of the Future seems to expand the binaries at play here, offering us a city before human existence as well as one after our time on the planet.

[Transforming Johannesburg in geometric, pyramid-like shapes (Mame Diarra Niang/ Metropolis)]

But no amount of cursory examination of Niang’s work could prepare me for the unhinged experience of her studio residency, Black Hole. The ease with which she transformed her in-studio residency space into a mystic’s enclave speaks to a self-awareness and an expertise in experiencing humans as cities in and of themselves — territories, if you will.

For her residency, Niang curated sounds, smells and a visual overload not meant to overwhelm but rather to foster a renewed search for reciprocal inspiration and communion with strangers.

Frustrated with lack of visibility, she nonetheless did not foreground her personal travails, turning our interaction into an engaging conversation that sought to interrogate her ethos as an expression of her actual practice rather than the practice itself.

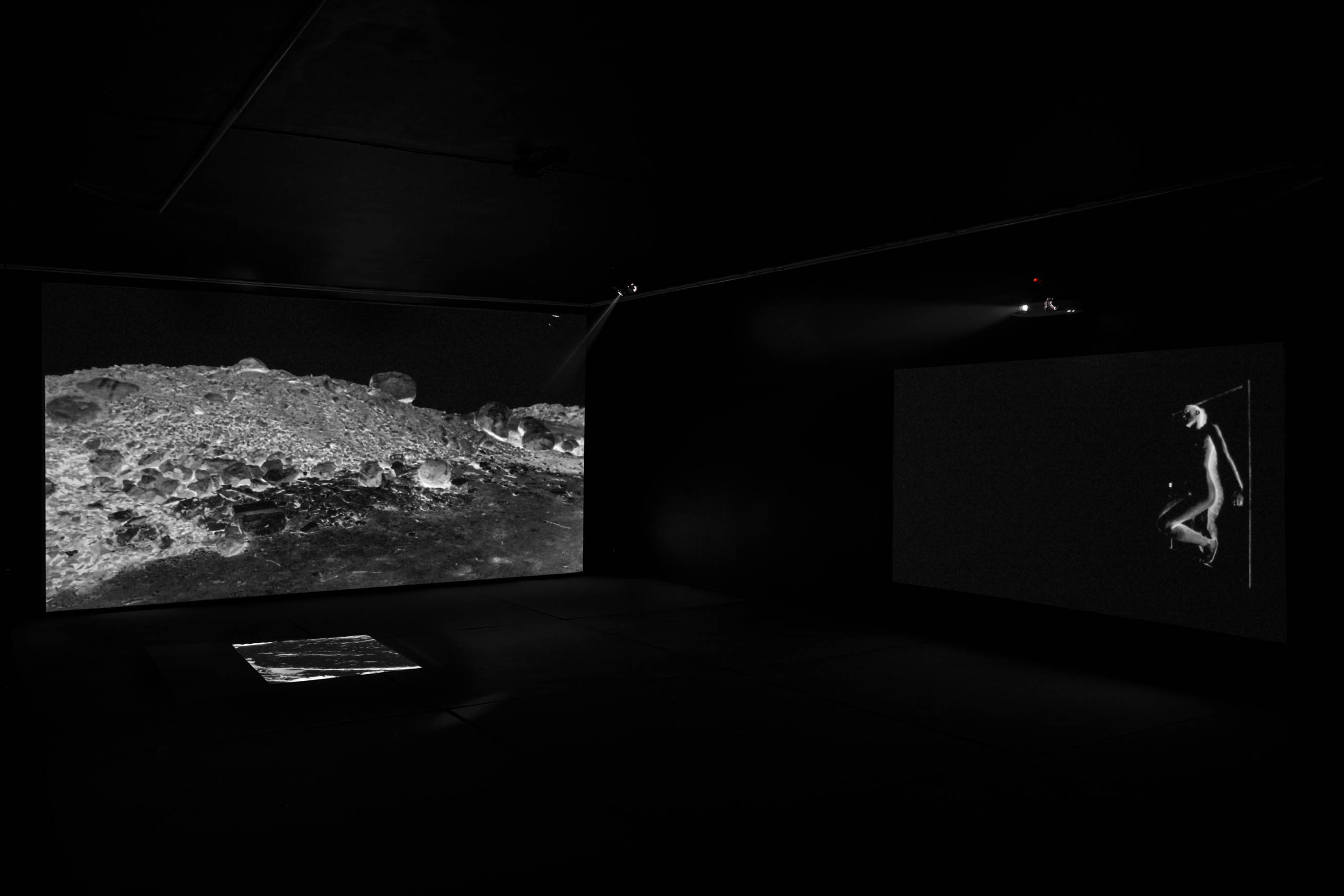

In Since time is distance in space, which plays out over multiple channels, Niang projected several slow-motion videos in a negative filter that depicted an alternate yet familiar world.

[Mame-Diarra Niang’s video work creates an alternate world (Mame-Diarra Niang/ Since time is distance in space)]

A quarry road (supposedly in Johannesburg) is seen as a shifting, moon-like surface, patrolled by lampshade satellites and a rotating, primordial, humanoid figure. The large-screen projections looped images that were beamed off screens affixed to prefab walls and the floor, leaving a vast black foam mat surface and perhaps a workstation where Niang had set up a tablet-controlled audio station. A lilting, post-internet vibraphone melody turned over on itself, bouncing off the walls and the souls in the space.

In a different part of the room, obscured by walling and curtains, was a projection over a Perspex screen tilted at a 45° angle that depicted “a comet transforming into a map”, as the geology-evoking Origin of the Future is explained on her website.

Niang herself was featured in some of the videos in the multiple-channel work, her naked form luminous through the filter, as if x-rayed or under water.

“Ancestral figures” — pharoahesque statues that are inanimate save for their manipulated movements — posit Niang’s vision of humanity as both elemental and bionic. Here, the idea of futurism is liberating, frightening and moot.

Niang has not been exhibiting work, although during the Joburg Art Fair, the obscurity of her location felt deliberate and maverick. .

In an atmospheric setting devoid of lighting except for the projected images, Niang created an experiential encounter with her work that forced an emotive reading of it rather than an intellectual one. People ended up trekking up to the studio anyway because of word of mouth during the art fair.

Given her disposition, the work gained further mobility as a study in vulnerability and yet communicated something other than self-pity or victimhood.

In a cathartic release, Niang turned herself inside out so we could observe ourselves through her.

The videos of the artist floating in a void — veiled, wind flapping the veil’s contours to reveal cyborglike, double-breasted torsos — suggest a release from a long-endured bondage.

During the two-hour visit, Niang hardly discussed her work, choosing to discuss context and getting to know her visitors instead. In a rare moment, she spoke of the timely need to be present in her work.

In it, Niang indulges us with images of her body that attain their luxuriousness and timelessness through stark, unsettling self-appraisal.

It is as if she is relocating herself in the world on her own terms. Her disposition is both defiant and reticent, as if it’s yet to be fully realised.