There are places in South Africa

A community is still reeling after the execution-style killing of 11 people in Marikana, Philippi East, in the Western Cape. Residents claim it was retaliation by a local gang for being targeted, sometimes fatally, by community patrols intent on exacting their own sense of justice. There are places in South Africa where communities no longer believe the police will protect them. And in some instances, people have taken to protecting their own, extracting their own restitution. Across the country from Phillippi, in Etwatwa in Gauteng, a community that turned to vigilante justice has reached a tenuous agreement with police. But in the wake of this compromise lies a trail of bodies and anguished hearts

In the late hours of the night, a whistle pierces the quiet of her slumbering neighbourhood. Busisiwe Ramaru (33) leaves her bed and arms herself with pots, pans, brooms and whatever else she can find to beat the burglar that has alarmed her whistle-blowing neighbour.

[The horrific necklacing of 16-year-old twins and the violent deaths of other alleged gangsters have led to an uneasy truce between Etwatwa residents such as Busisiwe Ramaru (above) and the police. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)]

“A lot of brooms have been broken because we’ve slapped people,” laughs Ramaru (33), a co-ordinator at the John Wesley Community Centre in Etwatwa, a township in Benoni, east of Johannesburg.

Ramaru calls the system the community’s “whistle alert”. In 2015, the same year in which 16-year-old twin brothers were necklaced in Etwatwa for being alleged gang members, Ramaru and her neighbours held a meeting. They decided that, because the police would not investigate crime for them, they would buy whistles, beat criminals up and deliver them bruised and bloody to the Etwatwa police station.

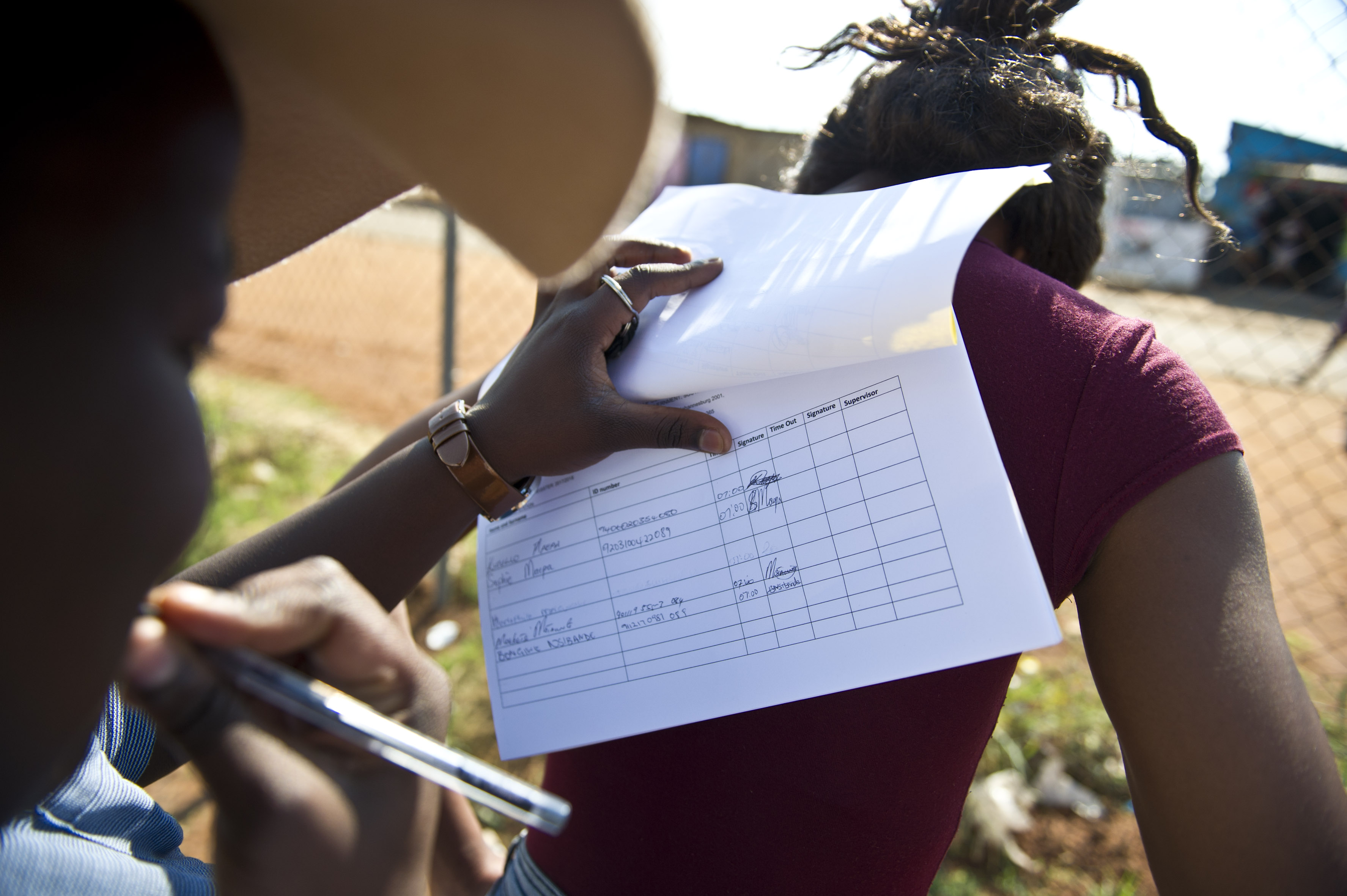

[People are signing up to help patrol the sprawling, crime-ridden township that only has a satellite police station. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)]

“If I cry for help every time and I do not get assisted, then what is there? Another chance? I think I must take my own stand and say: ‘This is enough’, ” Ramaru says.

The railway line is behind Ramaru’s house. It was along this track further into the township that the burned bodies of two suspected gang members were found last year. At least 50 people were arrested for public violence, assault with intent to commit grievous bodily harm and carrying dangerous weapons.

The Etwatwa police still remember the incident, nearly a year later. For those officers who will speak about it, it was a round of arrests that has become one of the legends of policing folklore in Etwatwa.

But no one was ever charged for burning the bodies.

The residents believed the victims belonged to a notorious group of gangsters known as the OVL (One Vision Lover) gang. They were youngsters, often of schoolgoing age, who initially tried to fight crime. They were helped by the police until the cops realised that the group was also committing acts of crime.

Assault, robbery and drug use became common OVL crimes. They would walk in groups and attack workers on their way home or steal from schoolchildren. The Mandela and Barcelona sections of Etwatwa became too dangerous to walk in.

Sithiembilie Gubula (33), a caretaker and chess coach at the community centre, wanted to start the OVL as a project to root out “nyaope boys”. But before he could begin, others took over, he said.

[Sithiembilie Gubula. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)]

He watched as his friends joined. His youngest brother, aged 17, was forced to become a member and fled to Cape Town to finish his matric after residents took matters into their own hands. They allegedly bought guns and, in some corners of Etwatwa, people whisper that men from a nearby Zulu hostel in Daveyton were hired to patrol the streets at night with their own weapons.

In the Mandela section of Etwatwa, where much of the violence took place, ordinary houses are said to hold dozens of guns. The men living there deny that their nighttime patrols to look for OVL gang members were violent or that they necklaced gangsters. Nobody patrols any more.

The survivors left behind

There’s a saying in Etwatwa that’s used often: “It’s in the past.”

In the cold winter months of 2016, Sifiso Simelane was at home when a group of residents came to look for him. It was the early hours of the morning. They had burned a tyre. They were waiting for him.

A large group dragged him from his house and took him to Chosasa Street where his friend, Gubula, had just left home to go to work. The tyre was huge, made to carry trucks. The stench of flames licking rubber fouled the air.

Hands and arms pulled Simelane into the centre of the fire, where his body rubbed against the skin of other young men who were inside the tyre.

And then the police vans came. The Ekurhuleni metro police department ran to pull the men out, and Simelane was rushed to hospital with burn wounds on the outside of his right and left calves. His skin had been seared off.

“It’s in the past. I don’t want to talk about it,” Simelane says, as he stands with his friends on a street corner.

There’s a tuckshop across the road, and the friends are sharing a bottle of Lemon Twist. From plastic cups, they sip the cool liquid on a hot October day.

Simelane no longer goes near where Gubula lives. He stays a few streets away, but refuses to leave Etwatwa altogether.

“This is my country. I won’t live anywhere else,” he says.

A few months after he was nearly killed, two burnt bodies were found on the railway tracks. And prior to that another two young boys had been lost to the flames.

Death of twin boys

In 2015, Sabelo and Samkelo Maisela were set alight with tyres around them, their limbs paralysed, squashed together in the unforgiving black rings. Their bodies were found in an open field, but their killers were never convicted.

Dudu Maisela, the twins’ aunt, is not surprised.

“Of course they were never found. It will never happen,” she says.

The twins’ mother died in 2012, and their father died before that. They grew up with their grandmother and Dudu, who was their guardian at the time they died.

Maisela still lives in Etwatwa, in a brown face-brick home with a black iron gate in front. Further down the street, a group of boys plays games and youngsters sit on the pavement, happily free of school for the holidays. Some of them know the Maisela name and the vicious story of the twins who died.

Dudu is reluctant to relive the deaths of the boys she cared for (“We are still grieving,” she says), but the mob justice in the township is something she has resigned herself to.

“It’s like that these days. If we report crime to the SAPS, nothing happens,” she says. “It’s in the past.”

Cops and robbers

They assemble in the morning outside the Etwatwa police station. On the back of their blue vests, the words “Etwatwa Community Patrol Team” and “Take Charge” are printed in shiny silver letters.

From 7.30am to 1pm, the Etwatwa Community Policing Forum (CPF) patrols areas in Etwatwa with police in an effort to prevent crime. Some of them are paid a R1 800 stipend, but most are volunteers.

[Etwatwa police officers and members of Etwatwa Community Policing Forum (CPF) at the satellite station. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)]

Etwatwa police station commander Colonel Molotelo Maoto estimates that the population of the township is close to 300 000 people, but there are only 150 officers on duty at the station.

“It will never be enough. You can have many police officers but if you do not have the community helping, then you cannot deal with crime,” he says.

Since last year’s murders, the OVL has disbanded. Its members are still alleged to be around Etwatwa but they no longer operate as a gang. Ramaru and Gubula credit community action for the drop in gang activity, but Maoto sees it differently.

“The community, I believe, now have confidence in the police. They will not do mob justice or mob patrols,” he continues.

But he may be overambitious. The Etwatwa police station simply doesn’t have the capacity to do as much as Maoto would like it to.

Musa Madonsela, the chairperson of the Etwatwa CPF, said the police station has few vehicles and no holding cells. It’s a satellite station and anyone caught for a crime has to be taken to the Daveyton police station, which is 10 minutes away.

At one stage, the station relied on just two cars — one to take charged people to the holding cells in Daveyton and the other to patrol the streets. It was common for police to arrive late at crime scenes and spend more time driving to Daveyton.

Plans are in the pipeline, Madonsela said, to turn the satellite police station into a more permanent fixture.

But for now, the community has turned to its whistle alert system and quelled the violent night patrols. A meeting with the police last year helped to put a stop to the community patrols.

“Their only request was that we intensify proactive policing, which means we do not [only] have to react to crime but patrol before crime happens,” he says.

Ramaru still keeps her whistle in her bag wherever she goes.

[(Photo: Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)]

She knows the burning deaths that have brought anguish to the township were a crime, but her lack of faith in the police has encouraged her to believe that no other option existed.

“We take the crime into our own hands,” she says. — Additional reporting by Gemma Ritchie