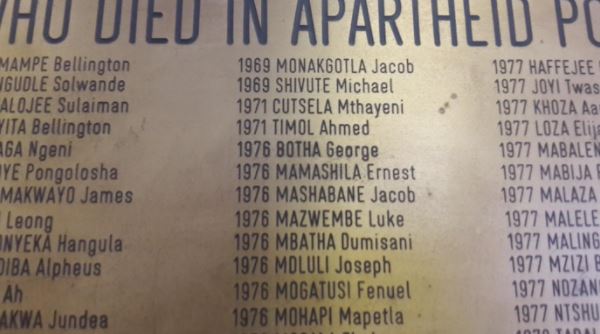

A plaque at JHB Central Police Station commemorating all the people who died in detention during apartheid. Included in the list of names is Ahmed Timol and Bantu Stephen Biko.

Judge Billy Mothle presiding over the reopening of the Ahmed Timol inquest last week ruled that the death of Timol in 1971 at John Vorster Square (now Johannesburg Central Police Station) was murder. Mothle said the cause of his death was severe brain damage, respiratory injuries, and blood loss.

Timol’s death was originally ruled a suicide by magistrate JJL de Villers at the first inquest, soon after Timol’s death. Timol’s mother, Hawa Timol, testified before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1996. Describing what she had seen when she received her son’s body – open wounds and blood stains all over his body – she said Timol was actually tortured to death by the Security Branch.

Mothle overturned the original ruling and officially ruled that Timol was tortured by the security branch causing physical injuries sustained before the fall. While the first inquest concluded that no living person was to blame for the death of Timol, Mothle said that Security Branch members, including Sergeant Joao Rodriguez – the last person to see Timol alive – were all responsible and conspired to cover up the murder.

Testimonies from Timol’s family, friends, colleagues and even torturers have brought to light the horrifying experiences anti-apartheid activists went through in detention.

The Wits Justice Project (WJP) spoke to two activists who were tortured during apartheid and to two people who were victims of torture after 1994. Their stories are chillingly similar and point to a continuing and systemic indifference to this very grave human rights violation.

Apartheid record keeping

There are no concrete statistics on the use of torture during the apartheid era because it was largely swept under the rug. The TRC kept its own records based on what they heard, during the period 1960 and 1994.

These records indicate that about 73 000 people were detained without trial during this period. Volume three of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report states that “Over 2 900 people reported 5 002 cases of torture. More than 2 000 instances of deliberate methods of torture […] were reported.”

According to the TRC, “Statements made to the commission indicate routine assault and torture of detainees by police. Beatings were the most frequently mentioned violation. Electric shocks were also common and allegations of poisoning were made. Some detainees returned home blind and/or deaf, some mentally ill.”

Human rights lawyer George Bizos also explained to the court at the reopened inquest how judges and magistrates turned a blind eye to these violations. “There were unfortunately some [judges and magistrates] who thought that their so-called patriotism to the apartheid regime was more important than justice and truth” he said.

Like Timol, anti-apartheid activist Phillip Dhlamini, who is the Pan African Congress (PAC) National Chairperson, was arrested four times during apartheid between 1977 and 1980 and also tortured at John Vorster Square twice – lucky to walk away with his life.

“I was taken to John Vorster Square with leg irons” Dhlamini told WJP, “There I was really tortured – electrical shocks and the money bag method.”

The ‘money bag’ method entails dousing a cloth bag with a drawstring attached to it in water. It was then put over a victim’s head and the drawstring tightened around their neck cutting off oxygen. “Then they punch you on your stomach” says Dhlamini.

This method is still used today. WJP’s Ruth Hopkins wrote an article in 2014 for the Saturday Star, about Noor Hoossen. After he was arrested on an allegation of robbery, the police took him to the police station where he met another man already handcuffed and sitting in the cell. Hopkins writes, “They pushed the other to the floor and pulled his handcuffed arms up behind his back, then they kicked him in the lower back. A plastic bag was pulled over his head, which they tightened with a seatbelt”.

Torture by the police did not disappear in the transition from apartheid to democracy. Raymond Lalla, an Umkhonto weSizwe veteran, was arrested and tortured in Bethlehem in 1990. In 1995 he became the head Crime Intelligence and Detective Services in the SAPS.

Lalla says that as the former head he and his team tried to actively move away from torture as a method to get confessions out of people. In order to achieve this, Lalla says, they tried to demilitarise the police service.

However, Johan Burger, former senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), argues that this did not have the desired effect. “I don’t think the idea of remilitarisation or militarisation has any influence on torture practices.” Instead Burger attributes the use of torture to a number of problems. “When you have inefficient detectives who cannot properly investigate cases, they will turn to torture because it is easy to use pain to extract information from suspects” he says.

Pressure on police due to high crime levels and huge caseloads create a mentality within the police that they “do not have the luxury to follow prescribed methods of investigation so they turn to torture” says Burger.

Finally he argues that the prevalence of torture has a lot to do with structural and leadership weaknesses, “There is poor command and control in the police and detectives know they can get away with it. There is no action taken against them until someone has enough evidence to lay a charge and it is investigation by IPID” he says.

Torture is still not dealt with effectively

In terms of international and domestic law, South Africa ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhumane or Degrading Treatment of Punishment (CAT) in 1998, but only introduced the convention in domestic law in 2013 through the Prevention of Combating and Torture of Persons Act.

The Act defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for purpose of obtaining information, punishment, intimidation or coercion”. The Act further explains that for the act to be deemed torture it must be committed by a public official or with a public official’s consent.

Despite these efforts, it is still prevalent. A worrying manifestation of this can be seen in the 2016/2017 Independent Police Investigative Directorate’s (IPID) Annual Report, which states that 173 cases of torture were received by the Directorate, compared to 145 cases the previous year.

According to IPID’s reports there have only been eight disciplinary convictions for torture under the new Act, all of which were lenient penalties (verbal warnings or small fines). These convictions were not criminal and were not handled by NPA.

Moses Dlamini, spokesperson for IPID, says the low rate of conviction is because the Torture Act “is relatively new” and therefore does not have a retrospective effect. He adds, “Assault is a competent verdict for torture. This means that the charge could be torture however based on the evidence presented the court could pass a verdict of assault/ grievous bodily harm.”

Clare Ballard of Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR), responding to Dlamini’s comment says, his “response is troubling because with a verdict of assault, we miss out (and thus, in my opinion, neglect to identify) the malignant motives on the part of the state official who is a torturer.”

Ballard adds, “‘assault’ fails to highlight the abuse of power, the secrecy, and the intention to punish or extort on the part of the official. If we don’t identify these features in our criminal law, we don’t prevent them.”

In terms of torture in prison, the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services’ (JICS) – an independent prison watchdog – 2015/2016 Annual Report states that they handled 15 cases of torture.

The WJP has spoken to many inmates in correctional centres around South Africa who have reported being tortured and mistreated during their time in prison and even during their arrest. Similarly, they tell us about electric shocks, assault, suffocation and lengthy periods in isolation.

In 2013 Ruth Hopkins exposed gross human rights violations in Mangaung Prison in Bloemfontein. One of the people she interviewed, Tebogo Meje, was assaulted and electro-shocked in the prison. His cell mate, a member of the 28s gang, was found with makeshift knives in his possession and Meje was left with the blame. “They asked him where he found it, and he said he knows nothing about these objects.” Meje explains, “They told me that guy is saying he knows nothing about this, so you must know about it, both of you must know about it.”

Unconvinced, warders poured water on Meje’s head and began electro shocking him. “It is their way of interrogating inmates so that they can tell them whatever they want to hear.” He said, “I’ve been through that process more than three times”.

When Meje tried to file a case against the warder it seemed as if the whole system was working against him. His doctor refused to give Meje his medical files needed as proof in his case. The police had taken an eye witness’ statement in the company of the same warder who tortured Meje. Eventually, the NPA threw the case out because of lack of evidence. Meje’s case soon collapsed.

However, Spokesperson for the South African Police Service (SAPS), Colonel Athlenda Mathe implies that these cases are reported with ease by victims. “The notion that torture is hard to report is baseless because those who allege that police members have tortured them are encouraged to report the matter at their nearest police station or through the IPID for immediate investigation.”

Gwen Dereymaeker, researcher at African Criminal Justice Reform, however, says her research has indicated that there is “a lack of knowledge about what torture entails and a lack of forensic knowledge to pinpoint torture injuries and not confuse it for assault injuries.”

Dereymaeker’s remarks, although a reference to the present day, ring true for Ahmed Timol’s case. His injuries were said to be injuries caused as a result of his fall out the 10th floor window and were used to cover up the brutal torture and abuse administered to him to the point of death. The plight of Timol in detention did not end with him nor did it end with the dawn of democracy. The inquest struck a chord with the WJP as it sounded all too familiar, 45 years after Timol’s death. In his conclusion in the judgement of the reopened inquest, Judge Billy Mothle said that there are lessons to be learned and the state should “develop an intolerance” to any kind of human rights violations.