Hugh Masekela collaborated with artists across genres

My collection of Ramapolo Hugh Masekela is far from definitive. Therefore, this annotated mix of his music is not so much a tribute to a son of the soil than it is a conversation between mohu Masekela and some of the artists he collaborated and lived with, starting with one of the most significant torchbearers of our time, Thandiswa Mazwai. In her liner notes, she speaks about how beautiful things like love do sometimes end abruptly. Did any of us expect Bra Hugh to be gone just like that?

Ingoma by Thandiswa Mazwai, featuring Hugh Masekela (Ibokwe, 2009)

Mohu (the deceased) Bra Hugh’s love and commitment to a pluralistic and border-free Africa is as monumental as the idea of pan-Africanism itself. His commitment is evident in a life’s work that celebrates heritage and collaboration across generations, especially with the pioneers of kwaito and its family trees after his return from exile. As a result, we listeners have experienced future-present sonic hymns in our lived experiences.

Bra Hugh is the embodiment of a household name precisely because, in and through his work, we share unforgettable encounters as if he had visited people’s homes — accompanying ceremonies such as graduations, weddings and after-tears in southern Africa over the decades.

His music resided alongside that of artists such as Dorothy Masuka, Letta Mbulu, mohu Brenda Fassie, Abigail Kubeka, mohu Thandi Klaasen, Thandiswa Mazwai, mohu Miriam Makeba and mohu Lebo Mathosa.

Bra Hugh is one of those artists who illustrates why intergenerational conversations, especially of the oral and sonic kind, are critical. To me, that’s why his projects always sound fresh and colourful, even when mournful and sombre.

That elders such as Masekela go ancestral with such convivial salutations as “Bra” says something about naming in this part of the globe. It goes further, this naming. Fly Machine Sessions, a Jo’burg-based archiving and DJ collective, thanked “Bra Hugh” for the “gospels” he offered. There is also mention of him as a “god”. Indeed, in Sepedi, we say that the first or most immediate ancestor is the parent.

In the absence of a father figure, a “bra” plays an important role where I come from. In fact, the salutation “bra”, unlike its kin “grootman”, has crossed gender boundaries. Not to be alarmist, but it seems we are running out of the archetypical bras in South Africa, or perhaps we lost them a long time ago.

Stimela by Hugh Masekela (Hope, 1994)

Indeed, there is hope — just eavesdrop on any millennial conversation. This generation has been exposed to Masekela’s life’s work. But it is also this generation that has challenged his opinions to a point that some of his views are categorised as being judgmental — as if it’s a case of “parents just don’t understand”. As a DJ, I have been told several times: “I don’t relate to the music you are playing,” especially by millennials. Yet Stimela cuts across generations on any dance floor I have served thus far.

Writing about his memories of his hometown of Witbank, mohu Bra Hugh recalled: “It was a tough town where African miners drank themselves stuporous to blot out memory of the blackness of the mines and the families and lands they’d left behind, often never to see again. But even when the burning coal dust blackened out the sun, we still had music to sing our sorrow and illuminate our ecstasy.”

This song captures the presence of a crowd that sounds like it numbers in the hundreds over and above mohu Masekela’s oratory and trumpet and several backing vocalists, punctuated by that unforgettably irresistible choooom/ choooom/ chooooooom/ choooooom.

Depending on the vibe, this Stimela version feels like a journey because it is vast in timbre, pace and time signature. It is the sound of people moving. It is simultaneously destabilising and soothing. Stimela is a liberation-seeking prayer. But liberation from what?

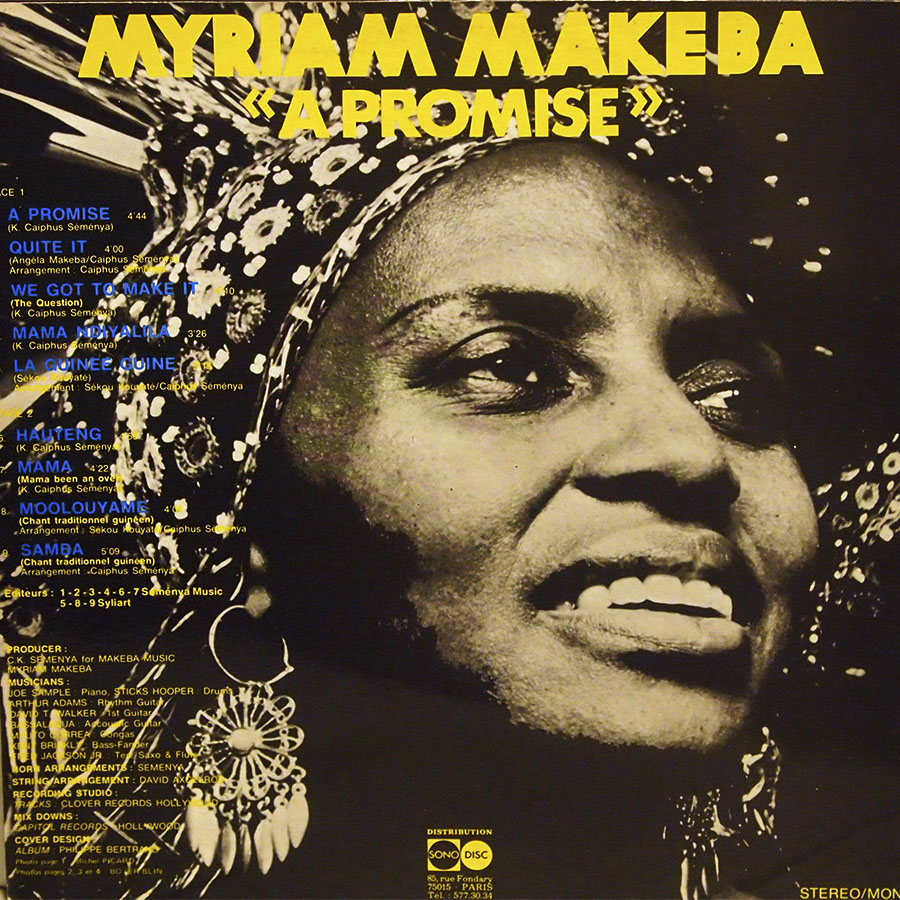

Quit It by Miriam Makeba (A Promise, 1974)

Mohu Makeba’s Quit It is liberation-seeking because it reminds us that with or without this loaded coal-train journey of blackened life, the one thing we can’t afford to do is to kill ourselves.

Substance abuse is one of the most talked-about biographical details of mohu Bra Hugh’s life. It is also deeply entrenched in a labour migration history that has reduced black lives to a disposable raw material.

Bra Hugh was one of the few public figures to come out, come clean and condemn substance abuse, just as Stimela and his outspoken repertoire did during and after the liberation struggle. His attitude to “struggle” was a holistic one.

Kwela by Mafikizolo (Kwela, 2001)

Yet there was and still is a lot to endure.

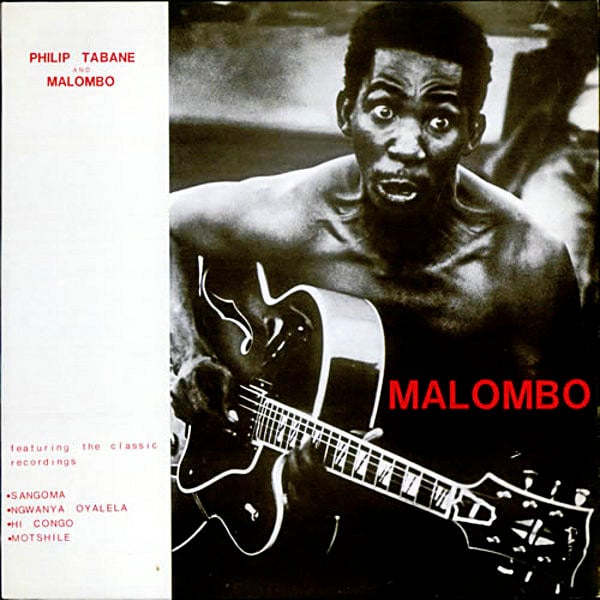

Ke Kgale by Philip Tabane (Malombo, 1996)

The ability to provoke and heal at the same time is hard, and it is central to mohu Bra Hugh’s legacy.

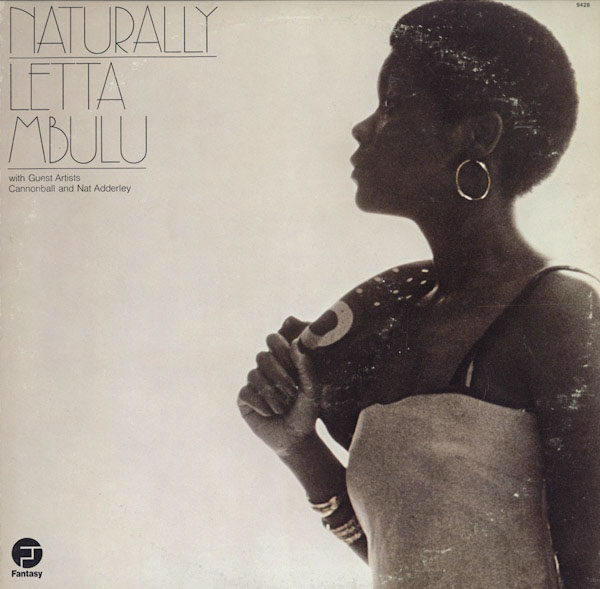

Setho by Letta Mbulu (Naturally, 1973)

Humanity.

Ntyilo Ntyilo by Hugh Masekela (Hope, 1994)

Ambuya Stella Chiweshe, born in Zimbabwe and living and working in Germany and Zimbabwe, is an artist who is committed to the preservation and innovation of indigenous practices.

She also believes that no one should be stuck in the past. I am reminded of these sentiments when I hear this version of Ntyilo Ntyilo, a South African evergreen that has enjoyed renditions by artists across the ages and years.

In Ghanaian parlance, this version is true sankofa — looking back while going forward, in which the chorus leads us to a place of improvisation and imagination. Whether this sankofa bird flies across the Atlantic or across Limpopo, it defies borders, just as mohu Bra Hugh did with his life’s work.

Spiyanko by Spikiri, featuring Hugh Masekela and Louie Vega (Habashwe, 2007)

Mohu Bra Hugh forcefully and strongly defended kwaito whenever he had the chance. It was neither lip service nor a riding of the bandwagon. Rather, it was a combination of

pride in home developments and commitment to intergenerational conversations.

Chileshe by Hugh Masekela (Black to the Future, 1998)

Ungabayeki bakubiz ’iKirimani.

Or makhafula. Or grigamba. Or kwerekwere. Or kaffir. Or nigga. Or lehwehle. Or lephusumani. Or stabane. Or moheteng.