(John McCann)

The future of a little-known South African-born start-up got infinitely brighter last week when, in just 20 seconds, investors reportedly poured a collective $10.8-million into the business.

This far exceeded the expectations of the team behind the project, Faceter, which had initially hoped its pre-sale, the first part of a so-called initial coin offering (ICO), would bring in about $800 000.

On Thursday this week, the next part of the sale commenced, with the project hoping to raise a cumulative $40-million. The sale window closes at the end of March.

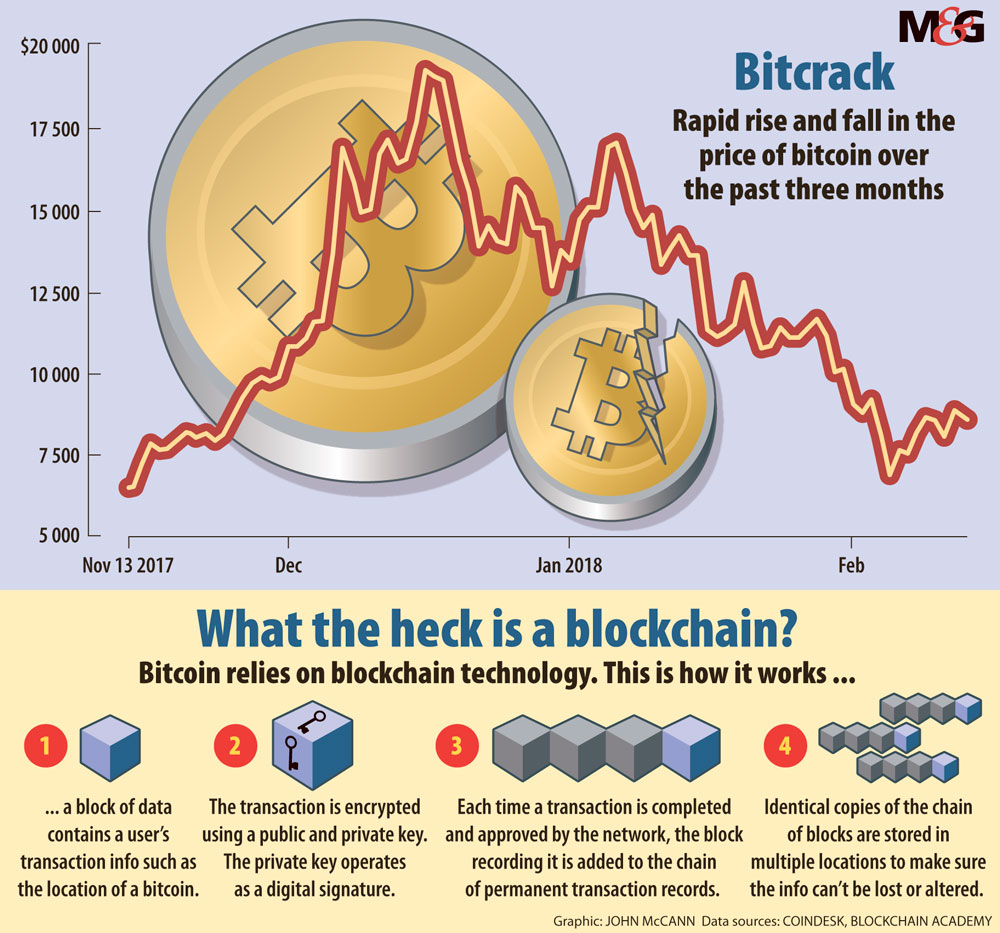

This rush to invest in Faceter comes at a time when leading cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin have come off record high prices.

An ICO is a kind of crowdfunding for tech business ventures and participants buy a token based on the strength of the offering contained in a document known as a white paper. The token is not necessarily a share in the venture but could instead be used to access products and services in future.

ICOs have become a buzzword among crypto traders fervently seeking to get in on the ground floor of what might be the next bitcoin. If trading in cryptocurrency is a high-risk business — and it is — then investing is ICOs is even more so.

About $4-billion has been raised through ICOs in the past two years but 10% of this has gone to scammers, says Nerushka Bowan, an expert in emerging technology law and a trainer at the Blockchain Academy.

She warns that people who take part in an ICO must be aware that they may also lose a lot of money, even if contributing to a legitimate ICO.

“It’s a high-risk game. A lot of people have made a lot of money in a short space of time, and some have also lost a lot in a short space of time,” Bowan says.

Port Elizabeth’s Robert Pothier, the brainchild behind the Faceter project and the token, dubbed FACE, is supported by his co-founder, Vladimir Tchernitski, and his development team based in Russia.

Faceter aims to make face detection and video-stream analysis available to mass users. It will run on blockchain technology, the underlying decentralised computing platform used by bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

Facester says in its white paper that it plans to use decentralised distributed computing technologies, also known as fog computing, to significantly reduce infrastructure and costs, making its product available to small businesses and mass consumers.

Pothier and the development team’s previous project, Pay.Cards, enables a mobile app to scan and recognise data such as that on a credit card with the use of a smartphone camera.

When Pothier was mugged on a Johannesburg street monitored by CCTV cameras and the police were unable to put the footage to any use, he prompted his team to move the card-reading tech to facial recognition of CCTV footage.

“Imagine if an unfamiliar face enters your property and a notification goes straight to your phone, or you can be told if your child has left school,” says Pothier, explaining what Faceter aims to one day achieve.

To run this kind of facial recognition software would normally require a big server, a costly exercise. But, if built on the blockchain, which uses decentralised processing power, the service becomes

economically viable for ordinary users and can be moved around the world.

Miners — the computers that validate transactions on the blockchain in exchange for cryptocurrencies — will be paid to perform recognition calculations.

ICO is a play on the term IPO, an initial public offering — the first sale of a listed company’s stock to the public. But the coin is not necessarily a share in a company or project, Bowan says.

In some cases, tokens can simply behave like a currency — like bitcoin — when it is accepted as payment for goods and services or where it is held as an investment. In other instances, the coin can be a utility token that offers future access to the application’s products and services.

This is the case with the FACE tokens, which Faceter says in its white paper do not represent equity in the company or its projects. FACE tokens are not designed or intended to perform or to have a particular value outside the Faceter ecosystem and should not be used or purchased for speculative or investment purposes, it says.

Bowan says tokens can often be hybrids offering some security, some utility or some currency features.

To have raised $10-million dollars in 20 seconds may not be the biggest ICO presale success story to date but these days it’s still “a pretty big deal”, Pothier says. He ascribes the success of the ICO to the strength of the white paper and the experience of the team.

“It definitely helps that we had something to show,” he says, noting the company has been conducting several pilot tests of its facial recognition software (although on a centralised basis) in a handful of South African businesses, such as casinos and a pizzeria.

ICOs were one of the fastest ways for a good company to raise money to invest in tech, says Potheir, but for Faceter the FACE token is also integral to the business model.

For every software licence sold, Faceter must burn, or destroy, a token to obtain an access key, which allows the customer to access the service.

The more licences that are issued, the more tokens are burned and taken out of the overall supply, theoretically pushing the token price higher over time.

Faceter will replenish its token reserve pool quarterly and will purchase tokens from holders based on market value of a FACE token but never below its nominal value.

When launching an ICO, the price of a tokens are typically fixed to another cryptocurrency, Potheir says. The price of the FACE was fixed to the price of ethereum, a prominent cryptocurrency, as at February 1 at $0.1, the reason given is “to protect contributors from exchange rate fluctuations”.

Faceter says it plans to hold the funds during the token sale as a diversified portfolio of cryptocurrencies and fiats (existing currencies such as dollars) to protect itself from ethereum and bitcoin price fluctuations.

According to Faceter, the FACE token price will be decoupled from ethereum’s when FACE begins to trade on cryptocurrency exchanges where it will then be subject to market forces.

ICOs are high-risk and people often put money in with little more than faith.

A recent example is a start-up, Prodeum, which promised to revolutionise the fruit and vegetable industry, but quickly revealed itself as an exit scam, shutting down its website and leaving only the word “penis” to greet duped participants, according to reports in Russian media.

A user claiming to be behind the scam alleged on a forum that Prodeum made only $3 000 from the scam. The supposed scammer wrote: “Remember that all ICOs are scams.”

An ICO scam — where a business opportunity is misrepresented before the scammers disappear with investors’ money — is fraud, Bowan says, but the problem is to catch the perpetrators.

“People are going through fomo [fear of missing out], thinking, ‘I should have bought bitcoin two years ago then I could buy a Lamborghini’, and scammers are preying on this and getting away with it.”

The offering can be as simple as a website, with a team of developers who turn out to be fake, after they have disappeared with the funds.

Another risk is when cybercriminals hack an ICO website just before it goes live and replace the bitcoin or ethereum wallet address to funnel the money into their own accounts.

Zain Wilson, an investment analyst at Old Mutual’s MacroSolutions boutique, warns those who want to use ICOs as investments must do their homework.

“As these are unregulated instruments, investors do not have either the protection of an overarching supervisory body, nor can they assume the level of due diligence met by, for example, shares listed on the JSE, have been met for an ICO.”

Regulators are taking different approaches on how to deal with ICOs, Bowan says.

The Securities Exchange Commission in the United States is taking the view that most of these tokens do not behave like currencies but are more like securities, and as such must comply with commission laws when necessary.

“As a result, a lot of these ICOs, when they launch will state that people from the US can’t participate,” says Bowan, who explains that it’s because they don’t want to get caught in these regulatory webs.

The Faceter white paper prohibits US citizens from participating in the ICO.

The blockchain for dummies

Blockchain technology underpins bitcoin as a currency as well as other types of cryptocurrencies such as ether or ethereum. The technology is decentralised, which means data is not stored in one location or by a single entity or organisation, says Sonya Kuhnel, the founder and managing director of the Blockchain Academy.

“As a result, the data on a blockchain is resistant to any single point of failure. It does not rely on trust between parties as it does not need a trusted third party to facilitate the transaction. It does not require the parties involved in the transaction to identify themselves or to know each other.”

The technology consists of a chain of “blocks” connected to each other and each containing information about the previous block and transaction data.

When a block is “completed” by the miners, in the case of bitcoin for example, it goes into the blockchain in a linear, chronological order as a permanent record of transactions that cannot be altered or removed.

Because Blockchain technology is decentralised, transparent and immutable no one can falsify, delete or change the data, Kuhnel explains.

Transactions stored on the blockchain can be independently verified and traced, making it easier to fight crime, counterfeiting and fraud.

“Similarly to how the internet provided the world with the free flow of information, so blockchain technology provides us with a way to enable the exchange of any asset of value over the internet instantly. For example stocks, music, securities, votes, frequent flyer points, intellectual property, scientific discoveries, and much more can be exchanged, all without the need of a trusted third-party or intermediary,” Kuhnel says. — Lisa Steyn