A congregant says he wrote to Anglican Archbishop Thabo Makgoba to ask for a meeting to talk about being abused by a priest but was told to go to the police first.

On a wintry Sunday afternoon last year, in Cape Town’s St George’s Cathedral, Gavin Hendricks* sat across from the priest who, he says, had sexually abused him for years as a child. Although the years of abuse ended more than three decades ago, the prospect of sitting face to face with his abuser filled Hendricks with dread.

“I was very anxious, but I had gotten to a place a few months ago where I just thought: ‘I need to approach this guy.’ You see, what happened then played a critical role in my life. I see the devastation that the abuse brought to my life, to my former marriage and also to relationships after that. At 52, I still struggle to form relationships with people,” says Hendricks today.

His anxiety was somewhat quelled by the presence of two people he refers to as his “safety net”: his brother and the dean of St George’s Cathedral, Michael Weeder.

Weeder, who had been providing Hendricks with counselling to better deal with the years of trauma, facilitated the meeting between Hendricks and the former priest whom he accuses of sexual abuse while heading the Cape Flats-based parish.

Weeder says that his role “was not so much counselling [Hendricks] as it was guiding him to the point of meeting [his abuser]”.

Following a recent open letter by South African author Ishtiyaq Shukri, detailing the sexual abuse he suffered as a child at the hands of priests in Kimberley, Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Thabo Makgoba issued a statement expressing the church’s “shock” and “distress” about the allegations.

Shukri’s letter was in response to Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu announcing his resignation as an ambassador for Oxfam, following a sexual abuse scandal at the international aid agency.

In his letter, Shukri wrote: “As far as I am aware, [Tutu] has never fully addressed [the] systematic and institutionalised sexual abuse happening in his own organisation [the Anglican Church].

“When Archbishop Tutu made his statement about Oxfam, saying that he is ‘deeply disappointed’ about the sex scandal, I was reminded of all the times I had been sexually abused by Anglican priests. Not that one ever needs much reminding; my own memories of the abuse I experienced are with me every day, and continue to impact my life on a daily basis. My memories dwell just beneath the surface of the veneer I have so carefully crafted to conceal them, covered in the shroud of silence I have draped over them since the first touch in 1978, when I was 10 years old.

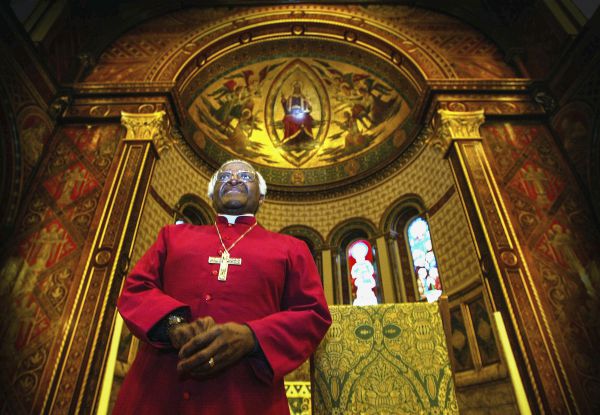

[Archbishop Emeritus Desmond disassociated himself from Oxfam after a sex scandal rocked the aid agency, but some say he has not addressed abuse in his own church. (Scott Barbour/Getty Images)]

By the time of Father Desmond’s inauguration as archbishop of Cape Town in 1986, I was 18 and still being abused. I was not the only one; there were others, too, many much younger. Today, I am speaking only for me, but my heart goes out to all of them.”

In response, Tutu’s office said he was “mortified to learn the suffering Shukri has described at the hands of priests”.

“Archbishop Emeritus Tutu has retired from public life, [but] he has the utmost faith in Archbishop Makgoba’s commitment to hold those clergy accused of wrongdoing to account, and support those whose trust in the clergy has been betrayed.”

Makgoba issued a similar statement. “The Synod of Bishops of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa was shocked and distressed to hear a report on Mr Shukri’s situation,” it read.

“In recent years, arising out of allegations of past abuse at church schools and institutions, I have established teams — including a lawyer, a psychologist, a priest and the head of the entity concerned — to investigate and advise me on these matters.”

Hendricks, however, finds the statement disingenuous. When he tried to report his abuse to the church, he was told to go to the police.

His former partner, Michelle Peters*, adds that she was “shocked” to read the church’s response to Shukri’s allegations, “because they knew about [Hendricks’s] case as far back as 2016”.

“[Reading that statement] brought tears to my eyes,” says Hendricks. “The nonchalant response of the church is disturbing to me. It seems that my pleas to highlight this to the church have gone unnoticed.”

In April 2016, Hendricks and Peters emailed Makgoba’s office, bringing to his attention Hendricks’s case and requesting a meeting with the archbishop.

The email written by Peters, which the Mail & Guardian has seen, reads: “[My partner and I] would like to meet you in an attempt to have his experience recorded in the annals of church history.

It is important to him — and for many others, we believe — to have someone hear what happened and to take necessary steps in order to contemplate justice and repair.

“He and I are under no illusions that he was the only child to be abused in this manner, nor do I believe it fair that the perpetrator continues to craft a life in the manner that he has, whilst men are reeling in the wake of his unconscionable assaults.”

Speaking to the M&G, Peters says: ‘“What we wanted was to have a conversation with the church about this, to draw attention to Gavin’s sexual abuse, for the church to have some sort of record of it and for there to be some kind of inquiry.”

They were never given a meeting. They were advised that Hendricks should lay a charge against his abuser and the church would then “take it from there”.

In responding to Shukri’s letter, Makgoba stated: “We usually urge victims of abuse to lay charges with the police and with church authorities. The police are often better equipped to investigate cases than we are, especially in cases which go back many decades and may have occurred in dioceses whose former leaders have died.”

Peters says that they were not advised to lay charges with church authorities. “The response we clearly received was to lay a charge at the police station,” she says.

Last year, a year after approaching the church and after decades of holding the secret of his abuse close to his chest, Hendricks walked into the Bishop Lavis police station to lay a charge against the former priest. There, he was told that, legally, he could not do so.

“It took a lot of courage to lay that charge. I was very intimidated and kind of reluctant, but I knew it was something I had to do. So, I was really disappointed. I remember thinking: ‘Why am I doing this? Shouldn’t I just let this whole thing go?’”

Yet in June 2017 the high court in Johannesburg ruled that section 18 of the Criminal Procedure Act, which states that, although crimes of rape may be prosecuted at any time, sexual abuse crimes lapse after 20 years, was irrational and arbitrary.

Acting Judge Clare Hartford invalidated the time limit for sexual offences and ordered that sexual offences could be prosecuted without the time limit until the Act is amended or 18 months has passed. The Act is currently before Parliament to be amended.

But, says Peters: “The long and short of [the church’s response to us] was for us to go the legal route.

But because of the law on prescription, the likelihood of any success in going that route was scant. So, in effect, it was little more than a silencing.”

Pointing out that Hendricks’s abuser was frequently relocated to different parishes, Weeder says that the church “likes to shift people” once it is rumoured they are sexually abusing children.

“Given that allegations of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church are so rife, one would expect the Anglican Church to be more proactive. The church was very vociferous in opposing state capture, which I fully support. One would have hoped, though, that that same energy could have been directed inward,” Peters adds.

Until the church forces itself to look inward, it appears that it is left to those who have experienced sexual abuse to find their own way through their trauma, in the way Hendricks did by choosing to meet his abuser face to face.

As to whether he found some closure after the meeting, Hendricks says: “The whole conversation was very awkward. His first comment was, like: ‘In your affidavit [to the police], you made me look like a monster.’ He told me that he’s changed, that he went through some counselling through the church. He kept making excuses and not taking any accountability for what he had done.

“I told him that the reason I called him there was twofold: that he apologise to me and also to my parents. You know, they invited him into our house and treated him like gold. But he gave no apology. Nothing. After that meeting, I felt drained … drained.”

“You know,” he adds, “my brother got married about 40 years ago and, on his wedding day, that priest gave my brother and his wife a Bible as a gift. My brother took that Bible with him to our meeting that day at St George’s Cathedral. After the meeting, he gave that Bible back to him. He was angry with [the priest] for what he did to me. I could see he was very, very angry, but all he said when he gave that Bible back was: ‘I don’t see you in this Bible. Go and find yourself in this Bible.’ [My abuser] just stood there, trying to explain himself, but we just walked away. We just walked.”

Months after the meeting, and now living in a different city, Hendricks says: “I’ve recently joined a church, but my heart just isn’t in it.

“But, you know,” he adds, “I still believe.”

Makgoba’s office had not responded to requests for comment at the time of publication.

* Not their real names

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the M&G

I pushed his hand away and said: ‘No, Father’

The dean of St George’s Cathedral, Michael Weeder, counselled Gavin Hendricks and facilitated his meeting with his alleged abuser. Asked why, Weeder says: “Look, I’m not neutral in this. I have my own history with this kind of thing, with my own parish priest trying to seduce me.”

Weeder then details how, at the age of 14, he nearly fell victim to sexual abuse at the hands of a trusted clergyman.

Along with other parish boys, the young Weeder would often visit the priest at the parish house.

“It was a classic situation of working-class laaities … You know, we came from homes where there was no electricity, but at the parish house there was even a radio. I mean, we could fry eggs there,” he laughs wryly.

“I was a young 14-year-old,” he says. “I was always wearing shorts and, I don’t know, maybe I came across as a bit effeminate. One day, [the priest] arranged for the kids to go out on an outing for ice cream. But when I got [to the parish house], the others weren’t there. There was nobody except me and the priest. We went anyway, and he drove to Mnandi beach. He parked the car there … in die bos. I was very uncomfortable sitting there with my priest, staring out at the bushes. I felt — I knew — that, on some level, I was fighting for my life.”

Recalling another incident, Weeder adds: “At another outing, Father put his hand on my knee. He then started sliding his hand up my inner thigh. I pushed his hand away and said: ‘No, Father.’”

The incidents left an indelible mark on the young man who would eventually head the oldest cathedral in Southern Africa. “Something profound happened to me then,” he says. “There was a shift in me; a shift in my affection.” — Carl Collison

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation‘s Rainbow Fellow at the Mail & Guardian.