Tilda Johnson

You know that black woman in Black Panther who helps Killmonger and Ulysses Klaue steal the vibranium at the British Museum? The one who shares a passionate kiss with the villain as they make a getaway after their heist, only for her lover to kill her as if she were inconsequential in the greater scheme of his ambitions?

Well, she is inconsequential to his plans, as we later see, after recoiling from the brief shock of how easily and how coldly Killmonger could be in taking her life when Klaue uses her as a shield.

But who is she and, more importantly, given the film’s groundbreaking focus and highlighting of strong black women, why is her role and eventual death so easily cast into oblivion?

I think she is used to counterbalance the strong women portrayed and embodied in characters such as the Dora Milaje led by Okoye, Nakia the spy, Queen Ramonda and the tech wizard Shuri. This is done through her deeds and her identity as an African-American woman compared with the African women in Wakanda and, perhaps to a lesser extent, as a fairer-skinned black woman who stands next to those in the mostly dark-skinned cast.

It is in this vein that I would like to put forward the case for this seemingly inconsequential woman, not because the film should revolve around her, but rather because, in reading the film and deriving meaning from it, there is a need to recognise that even the less obvious and silent moments carry weight, presenting to us new avenues through which we can explore other ideas.

It would help to have some know-ledge of the Marvel comics beyond Black Panther, so I will make the necessary comic book references to give perspective.

But first the problem of identity must be attended to. The other black woman who is presented as if devoid of a backstory has a name. It is Tilda Johnson, aka Nightshade, aka Lady Nightshade or Deadly Nightshade, and in the film she is played by singer and actress Nabiyah Be.

But who is Nightshade? This is where my proposition comes in, which is that perhaps in Nightshade we’re deprived of one of the strongest black female characters in the film.

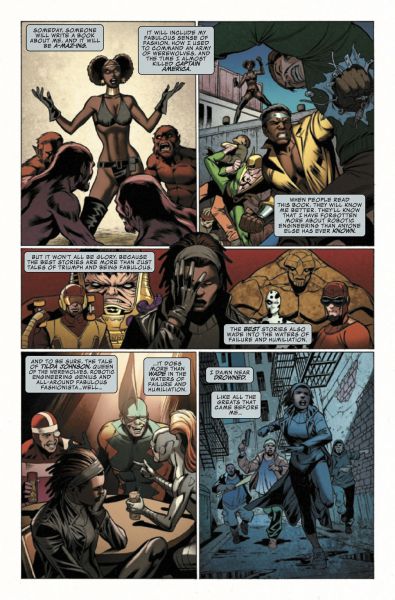

In the comics, Nightshade, a New York native, develops an interest in all things science and robotics but not having the means to study and get a PhD in physics as Killmonger or T’Challa do, she teaches herself and develops into Nightshade, a genius supervillain who is introduced to us as the Queen of the Werewolves in her first appearance in the 1973 issue 164 of Captain America.

In a later issue she turns Captain America into a werewolf, Cap Wolf — ridiculously corny but true.

In another Captain America comic arc, The Superia Strategem issues 389-391, Nightshade is part of an all-woman supervillain crew known as the Femizons, whose mission is to conquer the world and usher in a utopia founded and led by women.

She even develops a serum that turns men into women, which is probably one of the more radical things any villain has ever done — completely flipping society’s gender roles to restructure its patriarchy-based power relations.

This particular part of the trivia fits into another aspect of how Nightshade is used in the film, albeit briefly or perhaps unintentionally, and that is as an example of the relationships between black men and black women.

In the case and context of Black Panther, this system is made up of black American men, who are embodied by the constrained form of Killmonger, and black American women — represented in the film by Nightshade. Contrast this with the relationship between the African woman and warrior Okoye and her husband, W’Kabi, and you get a different perspective of these power dynamics.

[Deadly Nightshade, has a small role in the film Black Panther but in the comics she is a fully developed character whose enemy is patriarchy]

Okoye is able to stop a mild civil war by not only putting her life in harm’s way — a threat created in part by her husband — but is also strong and fierce enough to let W’Kabi know that she would put him down if need be.

Nightshade has no such luck. She is ultimately the victim of her man’s ideological ambition and, more specifically, his burning rage, which the audience is expected to believe is rooted in righteousness.

As I have already mentioned in this geeky presentation, Black Panther is obviously not about Nightshade. But if we are to accept that it is, in part, about the praiseworthy depiction of strong black women then surely it is only fair to look at how the film depicts all the black women in it.

Nightshade is too big a comic character to have been included only to be relegated to such a meaningless role and unceremonious end.

Her story throughout the Marvel comics is a complex one but also one that is consistent in its stance of being pro-woman — even if sometimes under the guise of being a villain. It is in this way that her complexity makes her very human, perhaps more so than the other women in the film.

How assuring then that, in the opening of the 2017 issue 4 of Occupy Avengers, her character confidently says: “Someday someone will write a book about me, and it will be amazing. But it won’t all be glory because the best stories are more than just tales of triumph and being fabulous.”