Child hero: Youths carry the coffin of Moeketsi ‘Stompie’ Seipei in Tumahole

There is no speaking of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela without hearing about the 14-year-old boy Moeketsi “Stompie” Seipei, an activist from the Free State and still a hero in the province, who was murdered in 1989.

After nearly 30 years of questions and speculation, there is still no definitive answer to the extent of Madikizela-Mandela’s involvement in the murder of Stompie, whose body was found in a wasteland near her home in Soweto.

Yet the stain that she committed the murder, or sanctioned it, has lasted longer and louder than the facts presented before two separate and full trials and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) headed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the 1990s.

Madikizela-Mandela was found guilty in 1991 for Stompie’s kidnapping and being an accessory to his assault. Three years earlier, self-confessed apartheid informer and the “coach” of the Mandela United Football Club, Jerry Richardson, was sentenced to life behind bars for the boy’s murder.

Neither the courts nor the TRC found that Madikizela-Mandela had murdered Stompie. Instead, the TRC found that the decision to prosecute Madikizela-Mandela, charged almost two years after the event, was influenced by political considerations.

“Strategic decisions with regard to the investigation and prosecution of Madikizela-Mandela appear to have been influenced strongly by the political circumstances and sensitivities of this period,” reads the TRC report.

The TRC found that Stompie was last seen alive at the home of Madikizela-Mandela and that she was responsible for his abduction. She was “negligent in that she failed to act responsibly in taking the necessary action required to avert his death”. During the hearings Tutu implored her to apologise for whatever had gone wrong. She refused.

Richardson, who died in prison in 2009, presented numerous and conflicting versions of how Stompie was murdered, including how he had slaughtered the boy like a goat, using garden shears, and whether he was sent by Madikizela-Mandela or not.

Henk Heslinga, who worked for the Soweto police at the time of the Stompie murder, claims in the 2017 documentary Winnie, directed by Pascale Lamche, that Richardson told him that Madikizela-Mandela had not ordered him to kill Stompie.

“We went to Jerry Richardson in prison. There he told me that Stompie found out that he was a registered informer of the security branch in Soweto. So he killed Stompie to cover his own tracks,” Heslinga said.

One of the people close to Stompie was Bishop Paul Verryn, who was entrusted to care for the boy after he was brutally tortured by the police. Verryn lived a few streets away from Madikizela-Mandela. At the time he was working part-time for the South African Council of Churches and had been relocated to Soweto in 1988.

Verryn remembers a very dark time. The apartheid regime detained children, tortured them with genital electrocution and other brutal means to break them.

“We treated these children, and after Stompie had been released after his own torture he was brought to me by Ace Magashule and Matthew Chaskalson,” Verryn said.

“I think he broke under interrogation and the two were afraid for his life because now people believed that he was impipi [an informer].

“At that time in Soweto, Winnie Mandela was idolised and things were not good. There were rumours of the violence perpetrated by the soccer club. Don’t mistake it, the people of Soweto lived in fear because of the club,” he added.

While he was on leave in December 1988 Verryn received a phone call informing him that Stompie and three other boys, Thabiso Mono, Pelo Mekgwe and Kenneth Kgase, had been taken from his safe haven because of rumours that he had sexually molested them. After a week of negotiations three of the boys were returned and Stompie’s body was found near Madikizela-Mandela’s house a few days later.

“It never became clear whether he was killed for being an alleged impipi or because he denied that I had sexually assaulted them or [because] he had found out about Jerry as an informer,” said Verryn. “What I do know is that we were all in a very dark place. When a country turns on their children something has gone terribly wrong.”

Stompie was buried and Verryn was cleared by the church of any wrongdoing.

But behind the scenes Madikizela-Mandela said she had become “a project for some” — the apartheid government used its propaganda machine to “discredit her” and for some in the ANC she was too radical.

Vic McPherson, a former national intelligence official, told Lamche in the Winnie documentary that in the late 1980s they employed a psychological warfare strategy against the enemy. “Everything was co-ordinated between the national intelligence, police force and foreign affairs. It was called covert strategic communications. One of the operations was called Operation Romulus, and Winnie was part of that.”

McPherson said the 40 journalists who worked for him would plant information in many newspapers to discredit Madikizela-Mandela, referring particularly to her private life.

When news of Stompie’s death spread, headlines about Madikizela-Mandela’s involvement flooded the newspapers, connecting the murder to her and her football club.

Stompie’s funeral was unlike many others in the township — it was not disturbed by the police because his murder was blamed on Winnie’s “bodyguards” and on her.

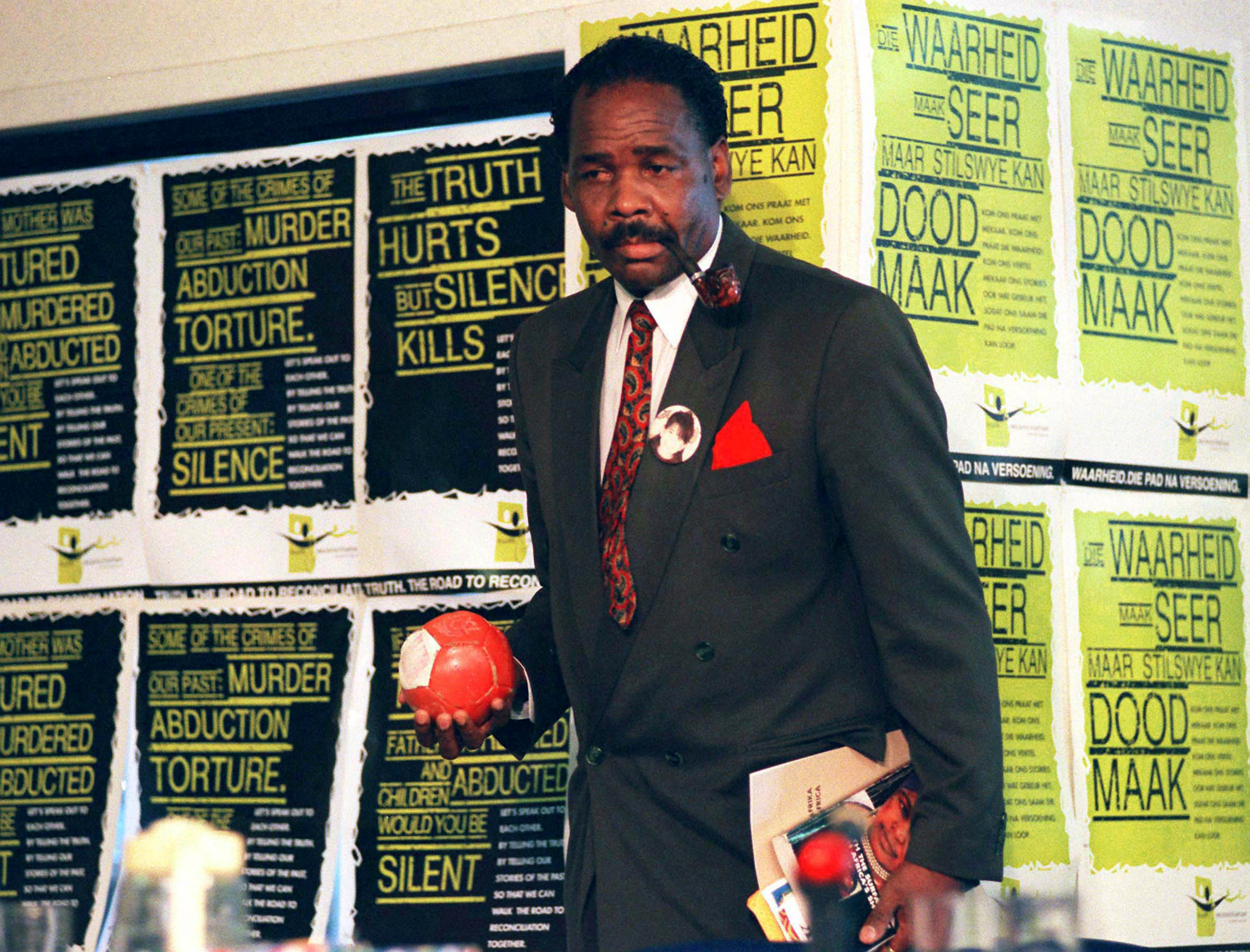

[Mandela Football Club ‘coach’ Jerry Richardson was convicted for the murder of the 14-year-old (Reuters)]

[Mandela Football Club ‘coach’ Jerry Richardson was convicted for the murder of the 14-year-old (Reuters)]

The tide started turning against her and divisions became apparent as many activists distanced themselves from Madikizela-Mandela, calling her a murderer. Richardson was sentenced for the murder. His version at the time was that “Mummy” had ordered him to kill the boy because he was impimpi.

During the TRC hearings the truth became murkier as apartheid operatives and those close to Madikizela-Mandela gave damning evidence.

But none of it would ever nail her for any of the dozens of abductions, murders and assaults her name was connected to. These included among other allegations the killing of Soweto doctor Abubaker Asvat, the attempted murder of Lerothodi Ikaneng, a former member of the football club, and the abductions of Thabiso, Pelo and Kenneth.

Former national police commissioner George Fivaz testified that Richardson was paid R10 000 after being convicted of Stompie’s murder to “oil his hands”, so he would co-operate with the investigation into finding the bodies of Lolo Sono and Sibusiso Tshabalala.

The TRC found that Richardson had murdered Sono and Tshabalala because they were believed to be police informers. This led to further questions about how a convicted murderer could be paid for information.

Richardson confirmed he was an apartheid informer and went back to his story that he had been ordered by Madikizela-Mandela to kill Stompie. This time he added that Stompie was tortured so brutally he was sure to die and that Madikizela-Mandela had participated in the boy’s torture.

But his testimony was contradicted by Katiza Cebekhulu, who was also part of the football club before he fled to Britain.

Cebekhulu claimed he saw Madikizela-Mandela stab Stompie twice with a shiny object. His testimony was contradicted by the autopsy, which stated that the boy was stabbed in the neck three times.

Fivaz said Cebekhulu was not a reliable witness and he had already given the police different versions of how Asvat was murdered in February 1989. His murder had also been linked to Madikizela-Mandela.

In a 2009 interview with journalist De Wet Potgieter, Heslinga, who had investigated the murder of Asvat, said his family alleged that Madikizela-Mandela was involved in the killing because the doctor had treated Stompie before he died and had exchanged strong words with her.

“We looked at every possible avenue to prove that Winnie Mandela was involved with the murder, but both accused denied they were involved with Winnie Mandela,” he said.

Heslinga said the two accused were sentenced to death, but days before their execution he convinced them to implicate Madikizela-Mandela.

“The execution was subsequently stopped and they received amnesty at the last minute when the death penalty was abolished. But in the eyes of death they again reiterated that Winnie Mandela was not involved and I also testified to this effect before the TRC. The TRC had accepted my testimony that Winnie Mandela was not involved,” he said.

The commission also confirmed that there was enough evidence to show that there was a concerted disinformation campaign by the security police against the ANC and that Madikizela-Mandela was a prominent target.

“Security policemen from Soweto admitted that she had been under constant electronic surveillance by means of telephone taps and bugs. They also admitted that Mr Jerry Richardson had acted as an informer. The testimony of former Soweto security policemen was, however, characterised by a lack of candour in disclosing the nature of their operations regarding Madikizela-Mandela,” reads the report.

Verryn, who has forgiven Madikizela-Mandela, said he remembers her as a woman who had deep compassion and passion.

Whether she was the one who killed Stompie or not, he said there is no way one could walk away from that time unscathed.

“He [Stompie] stalks me from time to time. There is no way that he didn’t linger with her for all these years. You must remember she was tortured and accused of all sorts of stuff. She herself was accused of being impipi,” said Verryn. “We can be very critical of all the spies and all the stuff that was going on and threatening people’s lives back then. But, without being there, no one has a clue.”