Heart: Sathima Bea Benjamin who was married to jazz musician Abdullah Ibrahim was warned not to release the album Lovelight because it was deemed too controversial. Photos: Sathima Bea Benjamin Personal Collection given to Carol Muller

“Jazz is a cry. It is a survival skill for the spirit. I think it must have started with a woman who just let out a wail. Then came the accompaniment.” — Sathima Bea Benjamin, from Musical Echoes, with Carol Ann Muller

Before El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (Malcolm X) would ascend the podium, he’d only ask that his host “make it plain” — meaning no fireworks and superlatives.

Sathima Bea Benjamin’s Winnie Mandela: Beloved Heroine, for all its apparent contradictions to notions of plainness, somehow remains unfettered by the ego, thereby directing us to the blue flame of Benjamin’s intent.

The singer, Abdullah Ibrahim’s partner (they divorced in 2011), bore two children with him. Accomplished and bearing an economy of expression marked by her precise lyrics and intuitive intonation, she seeks always, at least lyrically, to keep things plain. She speaks of the song arresting her compositionally.

“It woke me up from my sleep,” she says to Carol Ann Muller in Musical Echoes, their co-written biography, “and I had to call Don Sickler, the jazz arranger and trumpeter, and say, ‘Please write this down.’”

Ornate and playing out like a “mini-suite”, the song has hills and valleys, bearing changes of outfits as well as shifts in pace. Beloved Heroine starts as a steady, blues-based South African jazz progression before caving in, almost, into an elegiac ballad before finding its meter again.

“I wanted to write this song for Winnie, because I absolutely identified with her,” says Benjamin to Muller. “I could feel her pain,” Benjamin writes of her subject’s “soft, gentle eyes reflecting those unshed tears”.

When the parts come at her, she is in her tiny New York kitchen washing the dishes, she tells Muller: “I have a very tiny kitchen but at least when I am in there, running the water, I can’t hear anyone else. I use that time to sing without actually singing, to sing inside. I wash dishes a lot.”

In another account to Muller about a specific section of the song, “the Nomzamo part”, which refers to the unhurried blues groove that bookends the song, came “when I was making the children’s supper”.

Who is Sathima Bea Benjamin, meditating over the dishes, if not Winnie Madikizela-Mandela in Brandfort, perhaps? The children’s supper. The isolation. The career directed by service to the family. The nation.

This makes Beloved Heroine a slice of parallel biography. Less a song to a colossus and more an ode to a peer.

… Spirited soldier, life on the line,

Mother of the Nation, see her lovelight shine …

… Beautiful and brave is she …

A symbol of courage to all who strive to be free

In the book Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times, historian Robin DG Kelley writes that Benjamin — perhaps much like any other woman in male-dominated spaces, such as the recording industry — “was initiated into a world where she had to put up with sexual harassment from musicians on whom she depended on for practical skills, gigs, even transportation”.

There was what he terms a “near-rape” by Paul Meyer, her “benefactor”, and another telling parallel to Winnie: “Although she had spent the better part of a decade working for the ANC’s cultural wing and composing paeans to the movement, including Winnie Mandela: Beloved Heroine and her three-part Liberation suite, Benjamin was not invited to perform at president Mandela’s inauguration in 1994. Ibrahim was, however, and in her words, she had to ‘steal’ one minute from his allotted minutes so she could sing for her new president.”

[Shunned: Both Ibrahim and Benjamin worked tirelessly for the ANC during apartheid. But only Ibrahim was invited to perform at Nelson Mandela’s inauguration (Sathima Bea Benjamin Personal Collection given to Carol Muller)]

In 1994, of course, the isolation of Madikizela-Mandela, at least insofar as her proximity to Nelson Mandela, was pretty much etched in stone. She watched the proceedings from the bleachers as her daughter Zenani accompanied Nelson to take his oath of office. I wonder now, as I ponder their conjoined destinies, whether these two matriarchs thought of each other, as the machinations of the day conspired to erase their contribution to history.

Beloved Heroine was released in 1987. Trumpeter and arranger Don Sickler remembers little of the session except that it was recorded in the Jersey-based Van Gelder Studio, the same facility where John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme was laid down.

As for Benjamin, the controversies surrounding Madikizela-Mandela did little to dim her will to push forth with the message in her lyrics.

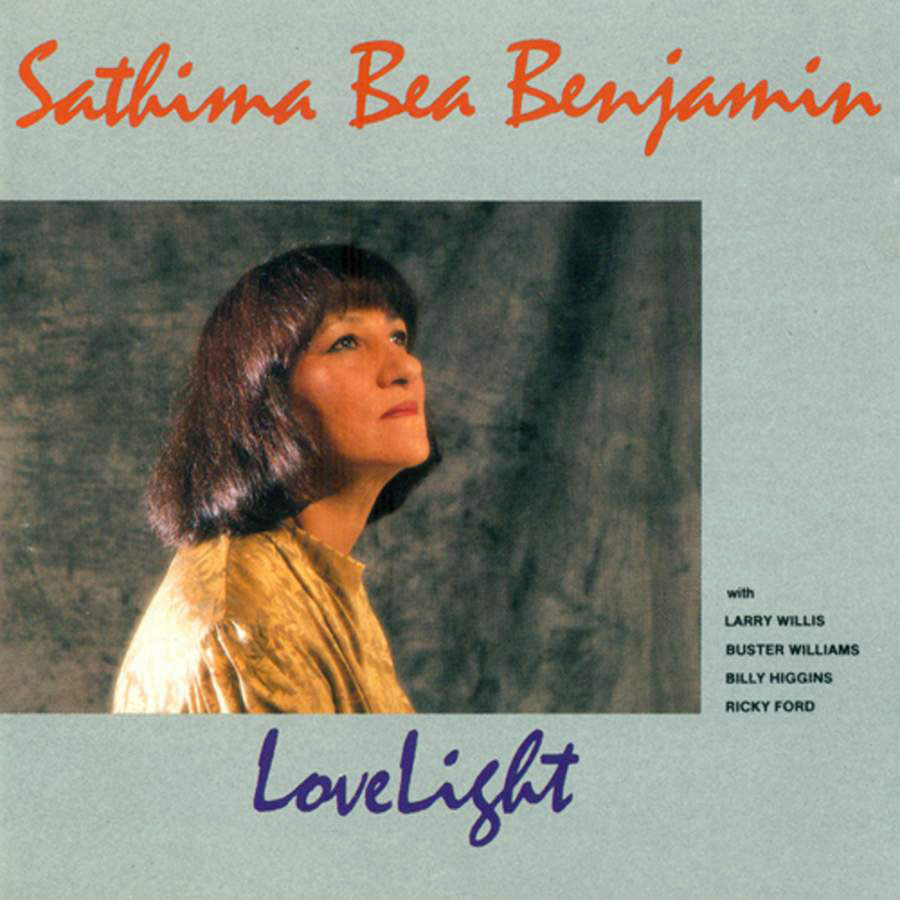

[Sathima Bea Benjamin was warned not to release this controversial album Lovelight]

In Musical Echoes, she states that she was warned not to release the album Lovelight. “But it’s a good sign for me if something is going to be problematic, because I am used to surviving against the odds. I did a lot of interviews about that song and have always asked why can’t we look at her track record of good things and not just her errors? She is human and, anyway, most of the time, we are just pawns in this big game … I put out that song and continued to sing it despite the controversies about Winnie because she spearheaded a movement for women. It took a lot of sacrifice. I am glad I wrote that song.”

Benjamin died in 2013 in Cape Town at the age of 76.

Being that she had the armour of words, in a form of expression that veers towards the abstract, she leaves a utilitarian yet versatile ode to Madikizela-Mandela. Woman to woman, Benjamin kept it “plain”.

*This story has been edited to reflect additional credits to Musical Echoes, a biography co-written by Carol Ann Muller and Sathima Bea Benjamin. Some of these had been incorrectly attributed to Deborah Kapchan’s Theorising Sound Writing, which includes a discussion of Muller’s work.