Unions claim shutting down coal mines will rob thousands of workers of their livelihoods.

The energy sector is in turmoil about the country’s shift to green energy and the issue of jobs.

Unions claim shutting down coal mines will rob thousands of workers of their livelihoods, but government and the renewable sector say a number of jobs will be created by renewable energy projects.

In submissions to the National Energy Regulator of South Africa, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) said 90 000 jobs would be lost because Eskom would shut down coal power stations in Mpumalanga to accommodate the renewable energy Independent Power Producers (IPP) programme.

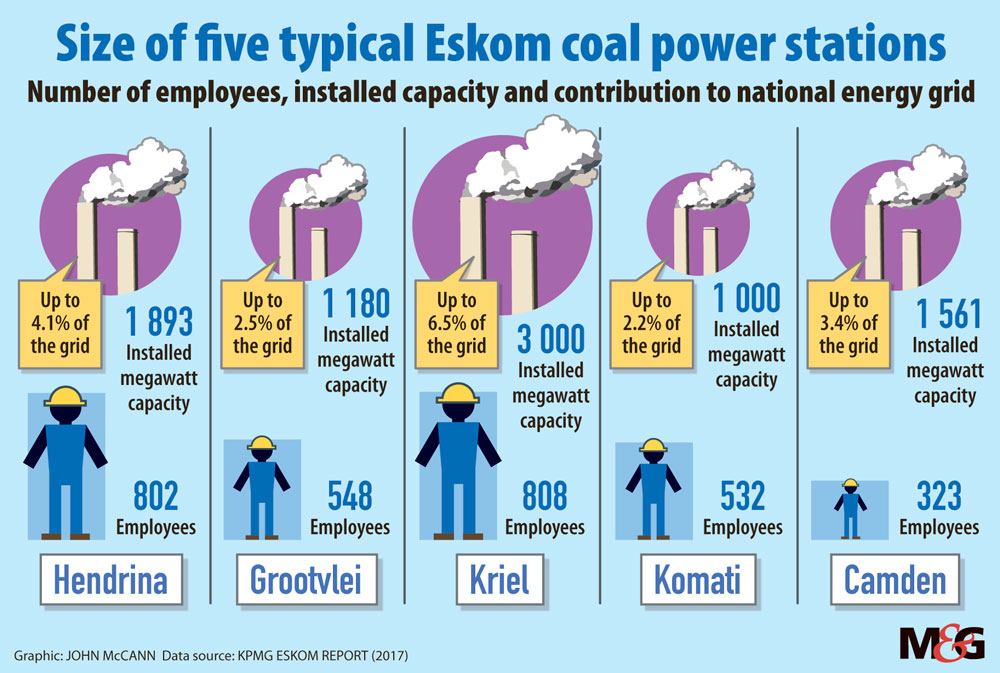

It based its claims on a KPMG report, released in June 2017, which focused on the socioeconomic effect of the closure of its oldest power stations at Hendrina, Grootvlei, Kriel, Komati and Camden, as well as reports by Eskom that the move would be accelerated, in part to accommodate renewable IPPs. The report says, in total, the five stations provide 3 013 permanent and temporary jobs and on average they sustain 92 961 jobs in the total value chain.

But Energy Minister Jeff Radebe has dismissed the idea that IPPs would cause job losses because the mines in question are at the end of their lifespan, so those jobs would have been lost anyway. He said the IPP projects would create 61 600 full-time jobs, mostly during plant construction.

Eskom said no coal-fired power stations have been decommissioned and none have been shut down as a direct result of the renewable energy IPP programme. “In 2017, five units from the older power stations, two from Grootvlei, one from Hendrina and two from Komati were shut down and placed into cold reserve because their running costs are higher than other units,” said the power utility.

“However, even if refurbished, the old stations will remain uneconomical to run compared to newer stations, be it renewable energy IPP or Eskom new build stations (Medupi and Kusile) because older stations are not as efficient as newer power stations,” said Eskom.

Last month Radebe reconfirmed the government’s commitment to renewable energy and signed off on power purchase agreements with 27 independent power producers of renewable energy. The programme will bring in R58-billion of new investment over the next three to five years.

In March, Numsa and Transform RSA tried to get an urgent interdict to stop Radebe and Eskom from signing the contracts but the high court ruled that the matter was not urgent.

Numsa spokesperson Phakamile Hlubi said, despite this, the union would continue the legal fight against the IPP projects. She said Radebe’s signing of the contracts was a “reckless decision” because it did not consider the effect of job losses and the economy.

Chief executive of the South African Wind Energy Association Brenda Martins said, although there might be short-term job losses, “such losses can be planned for and addressed so that reskilling programmes are undertaken. It is expected that over 13 000 construction jobs and a further 2 000 operations jobs will come on-stream with the latest round of signed projects.”

Nazmeera Moola, Investec Asset Management’s co-head of fixed income, said the assumption that coal mines would be shut down because of the commissioning of renewables, thus leading to the loss of many coal-sector jobs, was flawed and the old power stations would be shut down anyway.

“The question is how do we replace the power. Do we rely on new coal-fired power plants — that would be Medupi and Kusile — and we have seen that both those builds have been disastrous. Their costs have continued to escalate, they are years behind schedule and there are allegations of rampant corruption and mismanagement on both of those builds.”

Speaking at the Africa Utility Week on Tuesday, Radebe said the renewable energy IPP procurement programme had concluded 91 projects with a capacity 6 300 megawatts. Of these, 62 projects with a combined capacity of 3 800MW had already connected to the grid.

Numsa said there was no need for the renewable IPPs as Eskom has surplus capacity and electricity demand is flat and declining. The IPPs’ capacity would lie idle, which ultimately consumers would have to pay for.

“A kilowatt of electricity produced by IPPs costs up to R2.14 compared to the cost of a kilowatt of coal-produced electricity at 32c,” said Hlubi. “As a trade union we are not opposed to the energy mix and renewable energy in particular. We must transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy but it must be a just transition.”

But Moola challenged that and said that over the past decade “the cost of renewables has declined massively, where the cost of solar energy is well below what new-coal energy from Medupi is going to cost per kilowatt”.

A November 2016 presentation by the department of energy’s IPP procurement office showed that, between the first bidding window in 2012 to the fourth in 2105, the price of new solar energy decreased by 83% from R3.65 per kilowatt-hour to 62c/kWh. Onshore wind prices decreased by 59% from R1.51/kWh to 62c/kWh.

“It [renewable energy] is significantly cheaper than new coal IPPs, which is around R1.03/kWh,” said Martins. “In fact, the costs of new wind and solar PV power is even lower by 20% than Eskom’s 2016-2017 average price of electricity.”

Eskomsaid it had a seasonal excess which varied depending on factors such as demand, planned maintenance and unplanned maintenance. It noted that there were electricity constraints during peak hours, especially on winter evenings. “Renewables, in particular wind and solar generation, contribute to meeting the demand.”

Moola said renewable power was becoming the norm worldwide and South Africa had an opportunity to build knowledge and capacity, which could also be exported.

“We are never going to do that with coal-fired stations because everyone else is looking to build fewer and fewer coal-fired stations.

“If you look at how China has changed its energy mix over the past five years, it was opening a new Medupi every second week and now 80% of the new energy it is commissioning is renewable.”

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust financial reporter at the Mail & Guardian