Against all odds: Buhle Ngaba's 'The Girl Without Sound'is one of many to show the power of self-publishing in the digital era

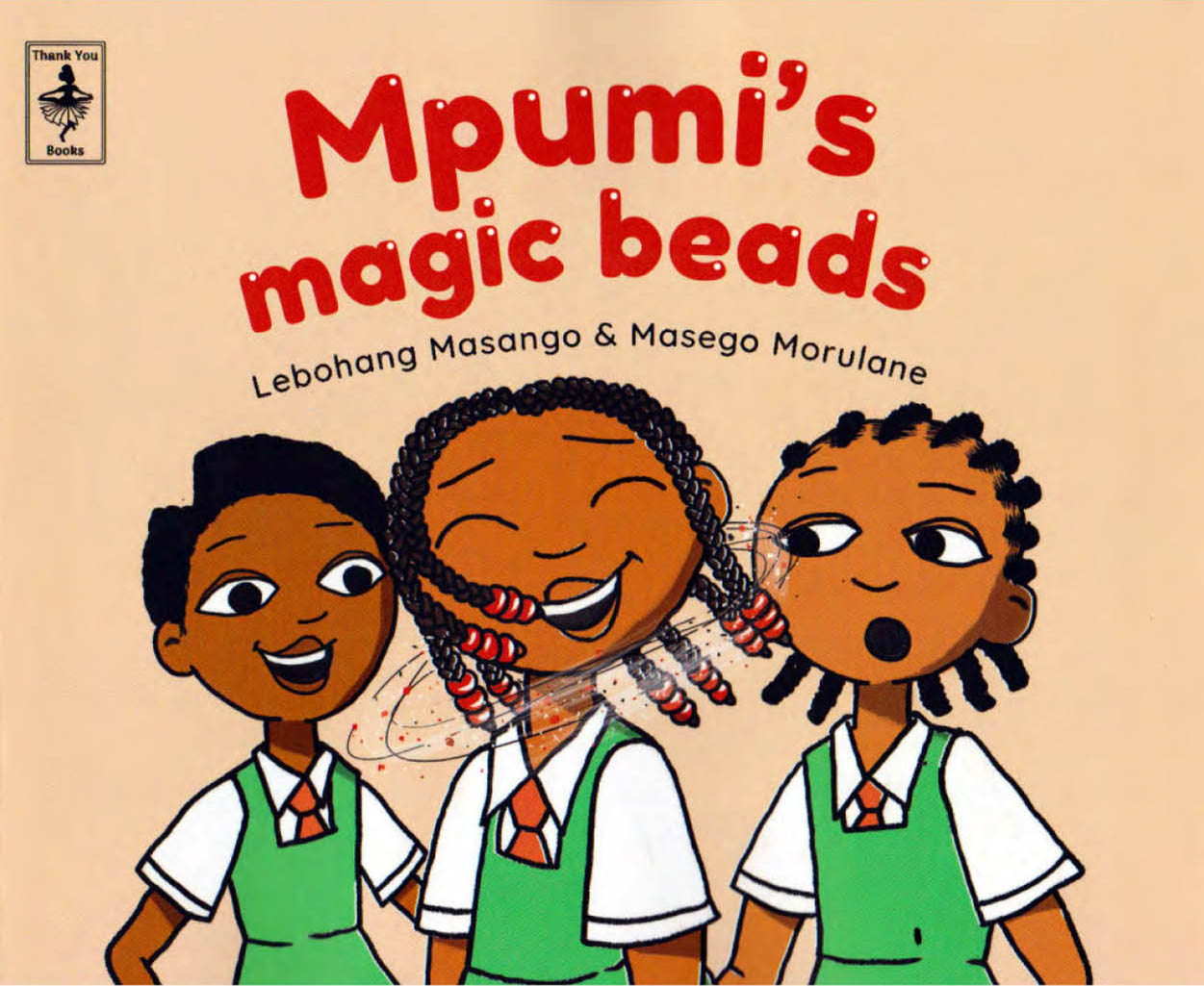

‘It’s a story about friendship, hair, self-esteem and affirmation,” says Lebohang Masango, author of Mpumi’s Magic Beads, her debut children’s book.

“There are a lot of children’s books in South Africa but a lot of them have village themes and farm scenes and that’s something I can’t connect to. And I’m sure there are a lot of children in urban centres who can’t relate to talking animals and rolling hills and that kind of imagery. That’s who this book is for.”

Last September, Masango, a Johannesburg writer and social anthropology master’s candidate, self-published Mpumi’s Magic Beads to critical acclaim. The story follows Mpumi and her two friends Asante and Tshiamo after they discover a set of magic beads in Mpumi’s hair. It leads to a series of adventures. The girls use the beads to make wishes, teleporting from Johannesburg Zoo to Gold Reef City, before the story’s main conflict, when a girl insults Mpumi’s hair (something that happened to Masango when she was eight).

Since releasing the book, the author’s weekends have mostly consisted of readings and she recently tweeted that she’d been invited to an international book fair. It’s a response that’s taken her aback.

“You put this out into the world and you can only hope it does well but some of the responses have blown me away,” she says. “There’s a parent who took the book to a recent school meeting to talk about cultural sensitivity and her own child’s hair. Or sometimes at readings, I’ll see little girls wear beads like Mpumi’s in their hair and that’s always wonderful to see.”

Masango is one of many local authors who’ve ditched the conventional publishing route in favour of self-publishing. With the current political landscape (the call to “decolonise South Africa” increases in intensity each year), perhaps it was only a matter of time before our literary establishment had a reckoning.

Some writers opt to self-publish as a way of writing back mainstream publishing’s insularity. When actress and writer Buhle Ngaba penned her magic realist fairy tale, The Girl without a Sound, in 2016, it was in response to the dearth of fairy tales featuring girls of colour. Such was the demand for the book that, in the week that she released it, 2 000 downloads were generated and the website she hosted it on crashed (as did her Facebook page).

“The book was written in defiance of the fairy tales we were told as little girls … stories about white princesses with blue eyes, flowing locks of hair and an overwhelming awareness of their beauty,” wrote Ngaba in the book’s preface.

Similarly, when #FeesMustFall activist Thenjiwe Mswane released her collection of isiZulu short stories, Uyesaba uZulu, it was her way of decolonising the language of local literature.

Masango chose to self-publish out of necessity. When she’d finished writing Mpumi’s Magic Beads she had a look at a potential publisher but was put off by their solicitation periods. “You go on a website and it says something like ‘we’re only accepting manuscripts in July next year,’” she laughs. “But I wanted to release it now. And, besides, I’ve always had creative control over my work. It isn’t something I’d want to give up any time soon.”

Masango’s sentiment is shared by Dudu-Busani Dube — a self-publishing powerhouse and literary giant in the making. Dube is the author of the Hlomu series: a trilogy of books she started sharing on her Facebook page in 2014. The series has gone on to sell tens of thousands of copies.

In a recent interview with online literary journal The Johannesburg Review of Books, Dube said: “I thought a lot about approaching a few publishers when I was sitting with a complete Hlomu the Wife for two months but something kept telling me they weren’t going to understand, because I have total disregard for the rules of literature as they are, and what is perceived as a good book or good literature.”

And that, perhaps, is the long and short of it. For many, mainstream publishing is its own self-contained (and self-limiting) universe. Head to the submissions tab of any publisher and each have similar parameters: no children’s books, no short-story collections, no poetry submissions, etcetera. And although these are in response to what the reading public supposedly wants, they narrow the options for an aspiring writer.

Still, some self-published authors tread where the mainstream fears to go.

In 2016, Phumlani Pikoli released his collection of short stories, The Fatuous State of Severity, after spending time in a psychiatric clinic. His collection features stories about mental illness, race and the nervous condition of the Twitter generation. This year, the book was rereleased by local publisher Pan Macmillan with six new stories.

Pikoli had always intended to self-publish the book. “We live in the time of Chance the Rapper,” he told online creative showcase 10and5 in an interview. “What’s stopping any of us from taking control of our means of production? In an age of democratised information, it’s so fulfilling to DIY art.”

The question remains: Is self-publishing actually worth it? The answer depends on each writer’s motivations. For every Dube, there’s a million other self-published authors whose books float around the internet with poorly designed covers and even worse editing.

Also, self-published works can’t be entered for awards, which usually have cash prizes (invaluable for writers in a country where books don’t sell that well). And there’s the terms people employ when talking about writers: there are writers and there are self-published writers; the latter’s prefix always followed by a silent judgment that seems to whisper: “Well, you’re not a real writer anyway.”

Still, if the success of this new wave of self-published writers is anything to go by, the practice is slowly slouching towards something resembling a new dawn.